From its origin in the play of verses added to successively by multiple authors to its

current form of a single standalone poem consisting of a three line, seventeen syllable poem

of five, seven, and five syllables haiku has retained its form as a play verse in modern

times. A book of haiku should come with a warning label that says something like: "Do Not

Enter Except to Play or You Will be Pecked to Death by Doves."

On page 30 Aitken shares an interesting distinction between English and Japanese

words for fruit and flowers. We are so accustomed to think of having a single word for

fruit, like pear, apple, plum and two words to refer to the flowers, pear blossoms, apple

blossoms, and plum blossoms, that it would never occur to us that in Japanese the situation

would be reversed there are two words for plum and only one word for plum blossom, etc.

This deserves to be meditated on there must a primacy of fruit for Western thought and a

primacy of blossom for Oriental thought. We in the West think of apple blossoms as the

forerunner of the primary function of the apple tree: to produce apples, whereas the in the

Orient, the plum fruit is the forerunner of the plum-blossoms of future trees. Feel this

distinction as it plays out in the next haiku from page 130.

How many, many things

They bring to mind

Cherry blossoms!

Here's what Aitken tells us about the importance of the cherry blossoms to Japanese

life.

[page 131] Instilled in the Japanese mind is the association of the

ephemerality of the cherry blossoms with the brevity of human life.

Blooming for so short a time, and then casting loose in a shower of

lovely petals in the early April wind, cherry blossoms symbolize an

attitude of nonattachment much admired in Japanese culture.

Compare this attitude with the Western attitude of the pretty cherry blossoms

presaging the appearance of the real purpose of the cherry tree: cherries.

Here's another haiku I wrote to play with what I think is the theme of the book as

given in its title, A Zen Wave. My haiku was inspired by the Basho one on page 38 and

Aitken's commentary on waving goodbye as a custom in Japan.

Wave & wave until

they are no longer in sight —

all that's left is Fall.

[page 39] People in the West, sometimes quite insensitive to the

importance of farewells, can learn from the Japanese, who say farewell

to the very end. They wave and wave until their friends are out of sight.

We in the West tend to see a visit of a friend as the fruit and the farewell as a trivial

falling blossom of the fruit tree. In Japan the visit is like the short-lived blossom that falls upon parting and the shower of petals must be enjoyed to the full it is the harbinger of future fruit, future visits. Here is Basho's haiku on

the subject:

For one who says,

"I am tired of children,"

There are no flowers.

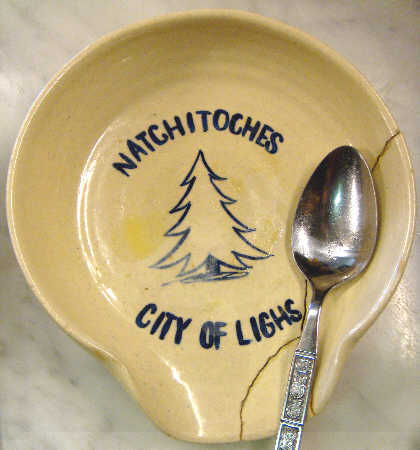

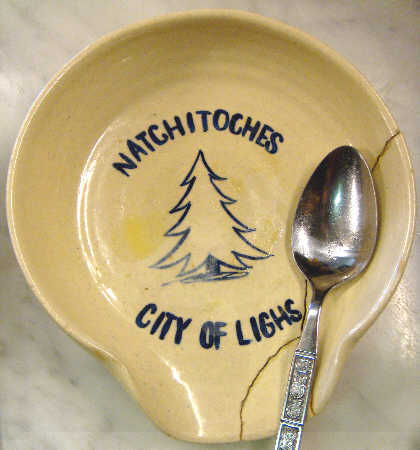

The next haiku I wrote was inspired by Basho's one on page 61 and the poem

"THAT" by Joyce Carol Oates on page 62. It has to do with imperfections. I bought a spoon

holder in a general store in the town of Natchitoches [nak ee tush'] that had a misspelling

on it, the 't' in the word 'lights' was missing. The lady who sold it to me also led tours of

the Christmas lighting decorations that the town is famous for along the Cane River. She

didn't want to sell it to me. Wanted me to get an unblemished one. I told her, "This holder

was obviously made by a human being, not a computer, and that's important to me." As

Aitken says on page 63, "Teeth protrude a little, a birthmark, an eye with a cast now

that's a unique individual."

That holder of spoons

Natchitoches City of Lighs

That's where my spoon rests.

"Meanings accrue if you ambigue." is a favorite saying of mine. Sometime one can

be too careful, too perfect. I was surprised to notice how careless spelling of words in a

blackboard presentation can add liveliness to the presentation. Aitken well understands that

aspect of communication, as he illustrates below.

[page 123] It is true that we must be clear, but it may be the wandering

thought that is a creative idea. Wu-men warns: "To be alert and never

ambiguous is to wear chains and an iron yoke." the Ts'ai Ken T'an

(Vegetable Roots Discourses) tells us: "Water which is too pure has no

fish."

In an age in which purified water from stores has replaced the drinking of water

from the tap, I take pride in drinking water from my tap that comes from the great

Mississippi River that drains the middle two-thirds of this great country. In taste tests it has

beaten the pure waters from highly touted mountain streams. If I might build on the quote

from the Discourses above, "Water which is too pure has no taste."

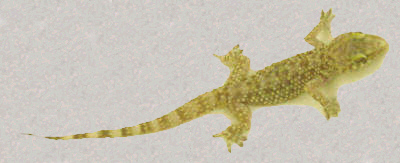

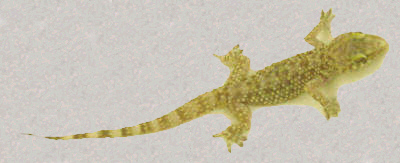

As I close I am watching a gecko feeding himself on my window. Each night that

follows day, he comes out as the light from my reading lamp attracts his food to his vertical

dining table on the outside of my window. You might see me now smiling and waving a

zen wave to you all the way to the end of our long goodbye . . .

Now! Days come, days go

A gecko on the window;

A smile is soul food.

~ See also Blowing Zen by Ray Brooks ~