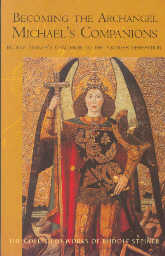

Who is the Archangel Michael? Why does he appear in sculptures with his foot on a snake or a dragon?

Why is he sometimes called St. Michael? Is he the same person as San Miguel, San Michele, or Saint Michelle?

What is his relationship to St. George, who also is shown slaying a dragon? And, lastly what is the correct

pronunciation of his name in English?

These are some of the questions which puzzled me when I first began to study Michael the Archangel. He

is certainly a being whose legends and myths have proliferated over the centuries and over many cultures. San

Miguel is his name in Spanish, San Michele in Italian, and Saint Michelle in French. In English we pronounce his

name My-Kull, but it is better to separate his name into three syllables, Mi-cha-el, to remind us that he is Micha

of el (Micha of God) el is the last syllable of all various archangels, Gabriel, Raphael, Samael, etal.

There is the city Archangel in Russia named after him, there are various cities, counties, islands, etc named

San Miguel, there is a museum in Italy named San Michele, there is a fortress Mont St. Michelle on the coast of

France, and there are many churches in America named St. Michael. Many churches, with other Saints' names,

have a statue honoring Michael the Archangel prominently displayed. In many cultures we encounter this powerful

archangel in many names. Somehow, in England, his legend got merged with that of St. George and the dragon

Michael is usually shown standing on a writhing dragon with one foot and applying his spear to it, whereas St.

George is usually shown on horse back applying his spear to the dragon.

What is the meaning of the dragon which appears ubiquitously with Michael the Archangel? Note that the

dragon is dark skinned and it is always portrayed alive and squirming, trying to escape, but held firmly with a

spear poised overhead ready to dispatch it. This represents the function of Michael the Archangel in our world,

and each of us must grab hold of that spear to assist him to kill the dragon. He appears with the sword and we

must help him complete the job, each in our own way. We are, rightly understood, companions of Michael and

he needs us to complete the job he is charged with. The evil represented by the dragon is alive and writhing,

striving to unleash itself upon the world and our lives, and we must take hold of Michael's spear and apply it to

the dragon in each of our lives.

What is the evil represented by the dragon? How do we become companions of the Archangel Michael?

These are among the many questions answered by this book(1). First, the question of evil evil is something we

all recognize when we see it, but few have ever created a better definition of evil than Rudolf Steiner when he

said, "Evil is a good out of its time." A person's death is not evil, unless by homicide or suicide it is precipitated

out of its natural time. The dragon wishes things for us that are not in their proper time and these things become

evils, no matter how attractive they may be to a majority of humans. Sustaining truths whose time is past is another

evil which is often overlooked. Our teenagers today, as in Steiner's time, recognized that many of the things they

are being taught have expired shelf-lives, are stale, tasteless, and in fact harmful to them, to the future that only

they will be able to achieve. As Louis Armstrong admonished parents about their children, "They'll learn much

more than you'll ever know(2)." One answer to the second question of how we become companions of Michael

is we do it by "Michaelic thinking" as described here from the Introduction by Chris Bamford:

[page xviii] Rudolf Steiner speaks of this process in many ways above all, perhaps,

as "Michaelic thinking," that is, the thinking of the enchristened heart that allows us to

think (cognize) the invisible in the visible so that we realize that we, too, are invisible,

supersensible beings. He also stresses that it is Michael's task and nature to reveal

nothing to us unless we bring to him something of our own earthly spiritual work. In this

sense, Michael is a mediator: bringing knowledge of the spirit in return for our work,

he ensures that we can properly (consciously) appropriate what we are given, rather

than opening ourselves to the risk of being overcome by it.

In basketball, if one takes a shot at the basket and misses the net, the rim, and the backboard, we call that

an "air ball". Steiner discusses in Lecture 1 at Stuttgart, three kinds of air balls: 1) air ball of the soul, 2) air ball

of human connecting, and 3) air ball of action. The air ball of the soul is the cliché or "empty phrase" which

generates a lack of thought, principles, and will. (Page 4) "Where the empty phrase begins to dominate, the inner

soul-experiencing of the truth dies away." With that human beings cannot connect with each other as they did

before. People pass by each other without understanding taking place. That is the air ball of human connecting.

You become aware of this disconnection when you hear someone talking about their point of view as being the

right one. One's standpoint is like a look at a tree from one spot on the ground. Until one has moved completely

around the tree and observed it from multiple standpoints, one cannot demand that one's viewpoint is the right

one. One's viewpoint is a map, and the map cannot represent all the territory as Alfred Korzybski rightly noted

the fullest view is the multi-ordinal view, taken from many standpoints as possible. Even then it is only a map,

but a much fuller one upon which to base one's judgments and decisions to act.

The third air ball of action is the development of the weakened will, "weak-willed in the sense that thought

no longer unfolds the power to steel the will in such a way as to make human beings, who are thought-beings,

capable of shaping the world out of their thoughts." (Page 6)

Here is Steiner talking directly to the youngsters of his audience and summarizing the three air balls for them.

One can almost feel their heads nodding in agreement as he says this:

[page 6] Now let me tell you, from an external point of view, what is living in your souls.

You have grown up and have come to know the older generation. This older generation

expressed itself in words; you could only hear clichés. An unsocial element presented

itself to you in this older generation. People passed each other by. And in this older

generation, another thing to present itself was the inability of though to pulse through

the will and the heart.

If this seems as fresh and new today as describing the world our current high school graduates face, then

it must be because every new generation faces these three air balls, and feel an urge to get on the court, get their

hands on the basketball, and show the old folks how to hit the baskets and score. The teenager hears the older

generation say some "empty phrase", e. g., "This is how the world is" and they feel an encrustation of ice form

which only the warmth in their heart can break through. The teenager today, as in Steiner's time, wants to throw

open the shutters of the past breathe freely of the future flowing in.

Steiner worked on the Goethean archives in Weimar and should be in a position to speak with authority on

Goethe's last words which are often misinterpreted as "More light".

[page 10] You know that among the many cliches which became current in the

nineteenth century, it was said that the great pioneer of the nineteenth century closed

his life by calling out to posterity, "More light!" As a matter of fact Goethe did not say

"More light!" He lay on his couch breathing with difficulty and said, "Open the

shutters!" That is the truth. The other is the cliche that has connected itself with it. The

words Goethe really spoke are perhaps far more apt than the mere phrase, "More

light." The state of things at the end of the nineteenth century does indeed arouse the

feeling that our predecessors have closed the shutters. Then came the younger

generation; they felt cramped; they felt that the shutters, which the older generation had

closed so tightly, must be opened. Yes, my dear friends, I assure you that, although I am

old, I shall tell you more of how we can now attempt to open the shutters again. We shall

speak further about this tomorrow.

As a child I wanted to know all about the world, how it works, and thus I began at an early age taking apart

things to figure out how they worked: clocks, radios, and numerous other devices which people had discarded.

As a boy of ten in 1950, I was able to find the first discarded television sets and take them apart and use their

parts to build crystal radios and vacuum tube radios. Back then a TV set lasted only a couple of years in the days

before transistors came into general application in electronics. I decided to study physics because of my interest

in how the various things I took apart worked. I didn't have any interest in building these things as an adult, so

engineering wasn't for me. By the time I took all that college could give me, I walked away into a world in which

all the magic was gone, into the cold world of the intellect, and I wondered why I found the world so empty. New

things such as computers came along to excite my imagination, so I programmed, helped design new computers,

built large gas pipeline control systems with them, and soon the world grew cold again. What was this

phenomenon that kept arising? I would learn something new and it would lose its magic? Till I studied Rudolf

Steiner I did not understand the deceptive nature of what was happening to me or why it happened. This next

passage will summarize what I learned from him.

[page 20] Certainly, in the sphere of the intellect, tremendous progress has been made

since the fifteenth century. But this intellect has something dreadfully deceptive about

it. For people think that in their intellects they are awake. But the intellect teaches us

nothing about the world. It is, in reality, nothing but a dream of the world. In the

intellect, more emphatically than anywhere else, a human being dreams, and because

objective science works mostly with the intellect, which it applies to observation and

experiment, science basically dreams about the world. It all remains a dreaming.

Through the intellect, a human being no longer has an objective relation with the world.

The intellect is the automatic continuation of thinking after one has been long cut off

from the world. That is why human beings of the present day, when they feel their soul

within them, when they get a feeling of themselves in their soul, are again seeking a real

link with the world, a return to the world. Here one makes a peculiar discovery. If, up

till the fifteenth century, human beings had positive inheritances, now they are

confronting a "reversed" inheritance, a negative inheritance.

Nowhere in my extensive education in various colleges was I taught about the basic emptiness of the intellect

I felt it in my soul, but I had been taught to distrust my feelings as something that was not real, only a illusion,

learning that from the very people most deeply stuck in the empty illusion of the intellect. I was feeling the

"negative inheritance" of humankind, and I earnestly sought to discover the reason for it, how that essential part

of my being worked. I know now that if I had been fortunate enough to attend a Waldorf School, this negative

inheritance would have been neutralized. Instead of experiencing the world through the polarized glasses of the

intellect which filtered out its feeling reality, my teachers would have opened the shutters of the world to me and

encouraged me to learn to experience the world directly through its phenomenon. Only then would I have been

interested in learning to apply the intellectual concepts which science provides. I would have had a positive

inheritance and a jump start into humanity.

[page 23, 24] Only the spirit can open the shutters, for otherwise they will remain tightly

shut. Objective science I cast no reproaches and do not mistake its great merits

will, in spite of everything, leave these shutters tightly closed. For science is only willing

to concern itself with the earthly. But since the fifteenth century, the forces that can

awaken human beings no longer live in the earthly. The awakening must be sought in

what is super-earthly within the human being. This is actually the deepest quest, in

whatever forms it may appear. Those who speak of something new, and are inwardly

earnest and sincere, should ask themselves, How can we find the unearthly, the

supersensible, the spiritual, within our own being? This need not again be clothed in

intellectualistic forms. Truly, it can be sought in concrete forms; indeed it must be

sought in such forms. Most certainly it cannot be sought in intellectualistic forms. If you

ask me why you have come here today, it is because there is living within you this

question: How can we find the spirit? If you see in the right light what has impelled you

to come, you will find that it is simply this question: How can we find the spirit which, out

of the forces of the present time, is working in us? How can we find this spirit?

As I entered my thirties, I became interested in psychology and psychotherapy, basically how the human

being worked. And I existed inside of a working model. As I did with clocks and radios, I studied broken ones,

humans with problems of various kinds, in an effort to learn how normally operating ones operate. I soon learned

to shun therapists who insisted that I be broken in ways I wasn't broken before I could work with them. I found

amazing insights in Freud, Jung, Milton Erickson, Virginia Satir, Paul Watzlawick, Richard Bandler, and John

Grinder, among many others, insights which revealed to me a whole world that existed outside of our waking day-time consciousness. These all helped me to expand my understanding of the human being, but it wasn't until

studying Rudolf Steiner that the spirit struck me like a lightning bolt (Page 33)and enkindled my deepest

understanding of what it means to be a full human being. The word, anthroposophy, as coined by Rudolf Steiner

for his spiritual science means knowledge (sophy) of the full human being (anthropos). It is a word that, rightly

understood, one should not stumble over in pronouncing, but should use its syllables as stepping stones into

understanding of the spirit which exists in every human whether they deny its existence or not.

Never during my academic career would I have thought of talking about spirit in a concrete way that

would have seemed quite paradoxical to me. Concrete was sensory-based experience only. Little did I suspect

back then how little concreteness there was to the way that I had been taught to think. How could I get a feeling

for the spirit when I had been to ignore my feelings about everything? Oh, I still had them, but I kept them hidden

and out of sight for fear of doing or saying something unscientific. To me the chemical of salt, mercury,

phosphorus, etc, were simply a combination of the properties described in my 3500 page Handbook of

Chemistry and Physics, 41st Edition, and nothing else.

In Lecture 3 Steiner strives to help the youngsters understand the concrete reality existing in the nature of

the spirit.

[page 25] Today, to lay a foundation for the next few days, I shall speak about the spirit

in the most concrete way. I must call on you to try to develop a real feeling for what is

meant here by spirit.

What is taken into consideration by a human being today? People attach

importance only to what they experience consciously, from the time they wake up in the

morning until they go to sleep at night. They reckon as part of the world only what they

experience in their waking consciousness. If you were listening to the voice of the

present and had accustomed yourselves to it, you might say, Yes, but was it not always

so? Did human beings in earlier times include anything else in what they understood by

reality than what they experienced in their waking consciousness? I certainly do not

wish to create the impression that we ought to go back to the conditions in earlier

epochs of civilization. That is not my intention. The thing that matters is to go forward,

not backward. But in order to find our bearings we may turn back, look back rather,

beyond the time of the fifteenth century, before the age I attempted to describe so

energetically to you yesterday. What people of that time said about the world is looked

upon today as mere fantasy, as not belonging to reality. You need only look at the

literature of ancient times and you will find that when people spoke of "salt,"

"mercury," "phosphorus," and so on, that they included many things in what they meant

that people are anxious to exclude today. People say today, Yes, in those days people

added something out of their own imagination when they spoke of salt, mercury,

phosphorus.

Another thing I was taught, not directly but by inference, was that the way humans experience the world

today was the way they always experienced the world. Therefore the alchemists who wrote about salt,

mercury, sulphur, phosphorus in strange ways were simply imagining things out of their ignorance, not out of some

ancient wisdom that we have since lost. What was it that people in those days saw?

[page 26] We do not want to argue about why this is so fearfully excluded today. But we

must realize that human beings saw something in phosphorus, in addition to what is seen

by the mere senses, in the way modern people see color. It was surrounded by a

spiritual-etheric aura, just as around the whole of nature there seemed to hover a

spiritual-etheric aura, even though, since the fourth or fifth century C.E., it was very

colorless and pale. Even so, human beings were still able to see it. It was as little the

outcome of fantasy as the red color we see today. They actually saw it.

Why were they able to see this aura? Because something streamed out to them

from their experiences during sleep. In the waking consciousness of that time, people

did not experience in salt, sulfur, or phosphorus any more than they do today, but when

the people in those days woke up, sleep had not been unfruitful for their souls. Sleep still

worked over into the day and their perception was richer; their experience of everything

around them was more intense. Without this knowledge as a basis we cannot understand

earlier times.

Sleep still worked upon humans during their daylight consciousness, but soon that era passed as human

consciousness continued to evolve. Soon those direct experiences of chemicals were treated as abstractions by

so-called modern scientists whose daylight consciousness gradually lost the attributes of sleep.

[page 26] The spirit continued as an abstraction in tradition, until, at the end of the

nineteenth century, one could not grasp the spirit in one's thinking, or at least one could

not sense it. External culture, which alleges such great progress, naturally attaches the

greatest importance to the fact that human beings act upon it with their waking

consciousness. Naturally, with this they will build machines; but with their waking

consciousness they can work very little upon their own nature. If we were obliged always

to be awake, we should very soon become old — at least by the end of our twentieth

year — and more repulsively old than old people are today. We cannot always be

awake, because the forces we need to work inwardly upon our organism are experienced

within us only during sleep. It is of course true that human beings can work on outer

culture when they are awake, but only in sleeping consciousness can they work upon

themselves. And in olden times, much streamed over from sleeping consciousness into

the waking state.

These insights into the nature of the evolution of consciousness inspired me to write this poem:

Waking Consciousness

With our waking consciousness

we can build a bridge to Paris

But we cannot build a bridge to our soul.

With our waking consciousness

we can fly a plane to Rio

But we cannot fly within our soul.

With our waking consciousness

we can work upon the natural world

But we cannot work upon

the inner nature of our soul.

Only with our sleeping consciousness

can we work upon

the inner nature of our soul.

With our waking consciousness

if we were to strive to stay awake

We would soon grow very old.

With our waking consciousness

we can work upon the natural world

But only while asleep

can we work upon our soul.

With our waking consciousness

we can read a book

and learn about the world

But with our waking consciousness

we cannot learn about our soul.

With our waking consciousness

we can have clever concepts in our head

But we cannot understand our soul

because these concepts are stillborn dead.

From pondering these thoughts, over time it became clear to me why the great physicist, Isaac Newton, gave

up the study of physics at middle age and spent his waning years studying the spiritual world. This is a fact which

one cannot find an explanation of in any current history of physics, other than Newton went crazy with old age.

[page 27] Read any current history of physics and you will find that it is written as if

everything before this age were naive; now, at last, things have been perceived in the

form in which they can remain permanently. A sharp line is drawn between what has

been achieved today and the ideas of nature evolved in "childish" times. No one thinks

of asking: What educational effect does the science that is absorbed today have from

the point of view of world-historical progress?

Books were read in a deeper fashion in earlier times, almost in a ceremonial fashion and that process of

reading "drew something out of the depths of people's souls."

[page 28] The reading of a book was actually like the process of growing: productive

forces were released in the organism, and human beings felt these productive forces.

They felt that something real was there. Today everything is logical and formal.

Everything is assimilated by means of the head, formally and intellectually, but no will-force is involved. And because it is all assimilated only by the head and is thus entirely

dependent upon the physical head-organization, it remains unfruitful for the

development of the true human being.

What is the effect upon one's soul of concentrating solely upon the "logical and the formal"? I think this is

nowhere better put than this quatrain by Samuel Hoffenstein. I was only 19 and a freshman in college when I

encountered this poet which had an enormous impact on me, especially this four-line stanza which I promptly

memorized, memorizing not something that came neither naturally nor easily to me. For 30 years I wondered,

held as an unanswered question, why was this stanza so important to me? The answer came as I began to read

Steiner and realize that, even at 19 the age of the young group these lectures are directed to I was feeling

the loss of soul and spirit in my nascent college career, I was remembering the future experiencing a time-wave

from the future of a time when I would come to understand the importance of these lines.

Little by little we subtract,

Faith and fallacy from fact,

The illusory from the true

And starve upon the residue.

Do you ever feel a tingle or a tinge of excitement while you are thinking? Chances are during those times,

you are not thinking logically or rationally. Logical and rational thinking deals only with dead concepts and can

have no invigorating effect upon the living soul and spirit. What was it like to have living concepts back in earlier

times? Something like having an anthill in one's brain.

[page 28] With regard to modern thinking, materialism is quite right, but it is not right

about thinking, as it was before the middle of the fifteenth century. At that time people

did not think only with the brain but with what was alive within the brain. People had

living concepts. The concepts of that time gave the same impression as an anthill; they

were all alive. Modern concepts are dead. Modern thinking is clever, but dreadfully

comfortable! Human beings do not feel the thinking, and the less they feel it, the more

they love it. In earlier times, they felt a tingling when they were thinking, because

thinking was a reality of the soul. Now people are made to believe that thinking was

always as it is today. But modern thinking is a product of the brain; earlier thinking was

not.

Computers are the latest form of machinery to which today's thinkers compare our brain. They say that the

computer is a metaphor for how our brain correlates and outputs thoughts. In Steiner's day, he said they would

say that the millwheel was a metaphor for how the brain worked. But notice that both the millwheel and the

computer are dead things, not living. And either one can only snatch and manipulate dead things. A millwheel turns

living grains into dead meal and flour, and a computer manipulates dead data, even if the data comes from external

sensors from the living world once it arrives in the computer, it is dead data stored formally and logically in

data banks, but dead nevertheless. This data can be displayed to show the semblance of life, but it is only a

semblance, not life. Even a sonogram of a living baby in the womb is merely a dead map giving only a semblance

of the living baby.

[page 29] Westerners love dead thinking, where they do not notice at all that they are

thinking. Today, not only when someone is talking nonsense but also when they are

talking about living things, Western people confess that a millwheel is turning in their

heads. They do not want what is living. They merely want to snatch at what is dead.

Think about this whenever you hear someone talk about computers learning to think they mean dead

thoughts, but never say so because they do not realize what a dead thought is because it is the only type of

thoughts they are capable of generating, up until now. I wrote a poem once about computers generating poetry.

I said that would not surprise me at all, but if computers were able to select a great poem from a bunch of

mediocre poems, that would greatly surprise me! It would be like expecting a computer to be able to have picked

out Picasso's first cubist painting and proclaim it to be a wonderful new work of art.

I don't consider myself an expert on living thoughts, having spent my early decades years focused mostly

on logical and formal thinking which deals with dead concepts. About thirty years ago, I began to sense the power

of holding an unanswered question. I noted how so often when I asked people a question, they had a ready

answer, usually an answer they heard from someone else. They would toss off this superficial answer as if it were

the God's truth apparently it was to them and go on to talking about something else. For myself, I would

hold such questions in my mind as unanswered, and wait for an answer to arrive. I would go to bed sometimes

wondering about the question. The answer would not come the next morning, maybe weeks, months, or years

later, but it would arrive and I would recognize as arriving in a form which was unique to the question I had held.

I believe that my process of holding unanswered questions is a way of stimulating living thoughts in myself.

Perhaps some of you, dear Readers, have noted a similar process in yourself.

[page 30] Living human beings, however, demand a living thinking, and this demand is

in their very blood. You must be clear about this. You must make your head so strong

again that it can stand, not only logical, abstract thinking, but also living thinking. . . .

The earlier thinking could be carried over into sleep. Then one was still something in

sleep. Human beings were beings among other beings. They were something real

entities during sleep, because they had carried living thinking with them into it. They

brought living thinking out of sleep when they woke up and took it back with them when

they fell asleep. Modern thinking is bound to the brain, and this cannot help us during

sleep. Today, therefore, in accordance with modern science, we can be the cleverest and

most learned people, but only during the day. We cease to be clever during the night,

when we face that world through which we might work upon our own being. For this

reason, human beings have stopped working on themselves. With the concepts we

evolve from the time of waking to that of sleeping, we can achieve something only

between waking and sleeping. We cannot accomplish anything on the human being.

People must work out of the forces with which they build up their own being.. . . It is out

of sleep that people must bring the forces through which they can work upon their own

being.

Everywhere we see commercials for body working machines which guarantee you a better body in 30 days

many people must be buying these machines to work on their bodies but how many people work on their

own being? Have you ever met a large imposing man, but when you talked to him all he could talk about was

bank business? Or met a small slight man and found his narrow frame supported a boundless spirit? The presence

of mere intellect does not nourish the spirit, it merely enlarges it by dilution, leading to what Steiner calls a "thin-soul skeleton" in the spiritual world.

[page 31] What happened when people of earlier times passed with their souls into

sleep? They were still somebody, because they had within them what hovers around

things what we call today a "fantasy." They bore this into sleep. Human beings could

still hold their own outside the physical body in the spiritual world. Formerly they were

somebody in the spiritual world between going to sleep and waking up. Today people are

less and less of a real entity. They are nearly absorbed by the spirituality of nature

when they leave their bodies in going to sleep. In true perception of the world, this is at

once evident to the soul. You just must see it, and you will be able to see it when you

acquire for yourselves the necessary vision for these things. Humanity must attain this

vision, for we are living in an age when it can no longer be said that it is impossible to

speak of the spirit as we speak of animals or stones. With such faculties of vision you

will be able to see that even though Caesar was not very portly in physical life, yet when

his soul left his body in sleep it was of a considerable "size" not in the spatial sense,

but its greatness could be experienced. His soul was majestic. A person today may be

one of the most portly of bankers, but when his soul steps out of his body in sleep into

the spirituality of nature, you should see what a ghastly, shrunken framework it

becomes. The portly banker becomes quite an insignificant figure! Since the last third

of the nineteenth century humanity has really been suffering from spiritual

undernourishment. The intellect does not nourish the spirit. It only distends it. That is

why human beings take no spirituality with them into sleep. They are nearly sucked up,

when they stretch out into the world of spiritual nature between sleeping and waking, as

a thin soul-skeleton.

When I first came to understand the spiritual world, it amazed me to find that many organizations and

individuals who were writing about the spiritual world were actually materialists. The biggest surprise was to find

this mode of thought among prominent members of the Theosophical Society, for example, those who talked

about spirit as being very diffuse matter or talked about the "permanent atom which goes through all our earthly

lives". Matter is still matter, however attenuated it is.

[page 32] Now, I really do not find any very great difference between those people who

call themselves materialists and those who, in little sectarian circles call themselves, let

us say, Theosophists. For the way in which the one makes out a case for materialism

and the other for Theosophy is by no means essentially different. If people want to

make a case for Theosophy with thinking entirely dependent upon the brain, then even

Theosophy is materialistic. It is not a question of the words one uses, but whether spirit

is in the words spoken. When I compare much of the Theosophical twaddle with

Haeckel's thought, I find the spirit in Haeckel, whereas the Theosophists speak of the

spirit as if it were matter, but only diluted matter. The point is not to speak about the

spirit, but to speak through the spirit. One can speak spiritually about the material, that

is to say, it is possible to speak about the material in mobile concepts. That is always

much more spiritual than to speak un-spiritually about the spirit.

In my early reviews of Steiner's books and lectures, I would form tables to help me and my readers

remember certain categories, such as the physical, etheric, astral, and I of the human being. This use of tables was

a carryover from my scientific training, and I was surprised to find that Steiner did not approve of the use of

tables. I stopped my practice of tables, but was not really sure what Steiner's objection to their use was until I

read this next passage.

[page 33, 34] In what I intend here and have always intended, the important thing is not

merely to speak about the spirit, but to speak out of the spirit, to unfold the spirit in

one's very speaking. This is then the spirit that can have an educational effect upon our

dead cultural life. The spirit must be the lightning that strikes into our dead culture and

kindles it to renewed life. Therefore, do not think that you will find here any plea for

rigid concepts such as the concepts physical body, etheric body, astral body, which are

so nicely arrayed on the walls of Theosophical groups and are pointed out just as, in a

lecture room, sodium, potassium, and so on, are pointed to with their atomic weights.

There is no difference between pointing at tables giving the atomic weight of potassium

and pointing to the etheric body. It does not matter at all. That is not the point. In this

sense, this kind of Theosophy or even Anthroposophy is not new, but merely the

latest product of the old.

Unless one uses it as a metaphor for an ineffable experience of the spiritual world, even such innocent

comments such as "there are good vibes in this place" can be seen as pointing to physical vibrations and

expressing a materialistic bias towards life. Only with a living education, such as that provided by Waldorf

Schools, can we come to speak of material discoveries in a spiritual way using living thoughts.

[page 36] We need a living evolution and a living education of humanity. The fully

conscious human being feels the culture of the present day to be cold and arid. It must

be given life and inner activity once again. It must become such that it fills human

beings, fills them with life. Only this can lead us to the point where we shall no longer

have to confess that we ought not to mention the spirit. It can lead us to where good will

flows into us and develops within us the inclination, not for abstract speaking, but for

inward action in the spirit that flows into us-not for obscure, nebulous mysticism, but for

the courageous, energetic permeation of our own being with spirituality. Permeated by

spirit, we can speak of matter. We shall not be led astray when talking of important

material discoveries, because we are able to speak about them in a spiritual way. We

shall shape what we sense darkly within us as an urge forward into a force that educates

humanity.

After discussing the depressing view of Spencer who strove to prove with the "crushing weight of material"

that moral intuitions cannot arise from the human soul, Steiner explains how his classical work, The Philosophy

of Freedom, was sent specifically to counter that view, that feeling extant in society at the time.

[page 38, 39] Into this mood of the age, my dear friends, I sent my Philosophy of

Freedom, which culminates in the view, with the end of the nineteenth century, the time

has come when it is eminently necessary that human beings contemplate how they will

be able to find moral impulses more and more by going back to the being of the human

soul itself. Even for the moral impulses of everyday life, they must resort more and

more to moral intuitions found in the soul, all other impulses will become gradually less

decisive. This was the situation I faced. I was obliged to say that the future of human

ethics depends upon the power of moral intuition becoming stronger with every passing

day. Advances in moral education can only be made when we strengthen the force of

moral intuition within the soul; when individuals become more and more aware of the

moral intuitions which arise in their souls.

Steiner's goal for humanity to have moral intuitions arising in their souls seems, on the face of it, too

amorphous, too idealistic to ever happen. How can people who are not perfect, who have their own selfish

desires and goals, ever find morality, on their own, one individual at a time? Wouldn't it be great if there were

some process we could put people through which would turn them into moral persons from then on? Some

educational process which would convert immoral or amoral people into moral people? Steiner book pointed

out that such a process was necessary, but only pointed to the goal and did not give specific directions for

achieving the goal. Any educational process has the difficulty of reaching everyone, since not everyone will submit

to the process. One despairs at the possibility of success in such an endeavor. I did. Until I met the ideas of

Andrew Joseph Galambos, who, in the 1960s, began to lay down his original ideas for attaining the kind of

freedom which entails moral intuition which Steiner pointed to some sixty years earlier. His ideas are like a vitalus

a virus which creates a positive result in those it infects. Once these ideas infect one, one is no longer able to

act reasonably without morality in every area of one's life. One begins to respect other people's lives, other

people's thought and ideas, and other people's material possessions never violating either their lives or any

derivative of their lives, using them only with the other person's permission. Like Steiner's Philosophy of

Freedom, not everyone will study Galambos's volitional science, so how can such ideas permeate to the average

person on the street? At the point when I began to despair myself at that possibility, along came a brilliant work

by Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation, which showed how the seeding of cells of cooperators (moral

people) in a population of cells of defectors (immoral people) will eventually result in the population becoming

all cooperators. He produced with computer simulation, something which Galambos said in his V50 course in

volitional science, that "Freedom, once built, will never be destroyed." Freedom, rightly understood, cannot be

fought for, but only built, and built one person at a time, and each person understanding freedom rightly and acting

out of that moral intuition will encourage others to operate morally or not prosper. They will discover the profit

of morality as they begin to discover the morality of profit. And they will discover it individually, one person at

a time.

[page 41] You see, real experience of the spiritual, wherever we meet it, always

becomes individual. Definition, however, inevitably becomes generalization. In going

through life and meeting individuals we must always have an open heart an open

mind for the individual. Towards each single individual we should be able to unfold a

completely new human feeling for every individual we meet. We do justice to a human

being only when we see in the person an entirely new personality. For this reason, every

individual has the right to expect of us that we should develop a new feeling for that

person as a human being. If we come with a general idea in our heads, saying that a

human being should be like this or like that, we are being unjust to the individual. With

every definition of a human being we really put up a screen to make the human being

invisible.

The definitions of Galambos which form the basis of his volitional science(3) create the kind of respect for

individuality which Steiner strives for. If we respect a person's life, thoughts and ideas, and possessions, then we

cannot treat them as slaves, workers, or place them in any demeaning category whatsoever. They are individuals

and like you and I, they are entitled to their lives, thoughts and ideas, and possessions, and you and I cannot

infringe upon those items, only arrange to use or share them with the individual's permission, in other words, by

cooperation. One can see it by these few words of mine which summarize years of study and thousands of

dollars of expenses on my part to acquire the knowledge upon which I base these words but these ideas of

freedom will eliminate all the negative aspects of capitalism from the world and bring the kind of moral intuitions

to the masses of humanity which Steiner so earnestly desires. A natural society will arise from these individual

moral intuitions.

Galambos brought forth exactly what Steiner intended his book Philosophy of Freedom to inspire: "the

founding of the moral life of the future."

[page 50] In other words, through my book, I wanted to show that the time has come in

which morality can continue in the evolution of humanity in no other way than that an

appeal is made to the moral impulses which each human being is able to call forth

individually from his or her innermost being.

In the natural society of Galambos the problems which Steiner refers to in the next passage will not arise,

or when they do, their appearance will be damped out in a culture which rewards moral intuitions, rewarding

those activities that are beneficial to all concerned and not rewarding those beneficial to only one person or group

which as its action infringes upon another's benefit or harms another person.

[page 43] Individual human beings, when they become active, come up against others.

Certain of these activities unfolded toward the outer world, happen to suit other human

beings to their benefit; other activities may be harmful.

We will, in effect, learn to act as Nietzsche describes, "I dwell within my own house and have imitated no

one". (Page 45) In one's own house, one does not resort to "intellectualism" which materialistic sea spume

splattered upon our life by logical and rational thinking devoid of spirit. It dries upon our skin causing irritation,

but does not bring us the living spirit of the sea of life.

[page 47] For unless the human being today honestly admits: I must grasp the living, the

active spirit, the spirit that no longer has its reality but only its corpse in intellectualism

unless I come to this, there is no rescue from the confusion of the age. As long as one

believes that one can find spirit in intellectualism, which is merely the form of the spirit

in the same way as the human corpse is the form of the human being, human beings will

not find themselves. . . . They get nothing but a dead thing, a dead thing that can

wonderfully reflects what is dead in the world, just as one can still marvel at the human

form in the mummy. However, in intellectualism we cannot get what is truly spiritual any

more than a real human being can be made out of a mummy.

This was the task that Dr. Frankenstein attempted to do in Mary Shelley's classic horror story. Her story

taught humankind that whenever we strive to create something living out of our intellectualism, we create only a

horror. This theme has since been reiterated in many classic stories, every one of them which falls into some

category of horror story. Intellectualism is filled with what Steiner called the "empty phrase" the cliches which

reveal themselves to be but "a revival of old concepts overreaching themselves." Instead Steiner tells us "we need

an intensively developed feeling for the truth." (Page 48) This undoubtedly resonated strongly with the young

people in his audience.

[page 48] What we need is truth, and if any young people today acknowledge the

condition of their own souls, they can only say: This age has taken all spirit out of my

soul, but my soul thirsts for the spirit, thirsts for something new, thirsts for a new

conquest of the spirit.

My own summary of Lecture 4 took the form of this short poem, "The Empty Phrase":

The empty phrase

overreaches itself

The empty phrase

seeks to make a mummy

into a man.

The empty phrase

seeks to make a movement

without a plan.

If we go back in the evolution of humankind, we find a time when moral intuitions rose up within people

naturally, in the same way as it does in our children today who represent for us this earlier form of humanity. It

is why children are so attractive to adults there is an unconscious knowing that children represent a form of

knowing and moral intuition we have lost in our modern world, but what was once the natural ability of every

human being. People did not argue about the existence of God, they simply said, "He stands there."

[page 51] Before the fifteenth century, people did not speak in indefinite the

indefinite was already the untruthful terms as was current later. When speaking of

intuitions, also of moral intuitions, people spoke of what rose up within their inner

beings, of which they had a picture as real as the picture of reality they had when they

opened their eyes in the morning and looked at nature. Outside they saw nature around

them, the plants and the clouds; when they looked into their inner beings, there arose

the spiritual, which included the moral as a given. The further we go back in evolution,

the more we find that the rising up of an inner existence in human experience was a

matter of course. . . . Had anyone during the first centuries of Christianity spoken about

proofs for the existence of God, as Anselm of Canterbury did, no one would have known

what was meant. In earlier times they would have known still less! For in the second or

third century before Christ, to speak of proof for the existence of God would have been

as if someone sitting there in the first row were to stand up and I were to say, "Mr. X

stands there," and someone in the room were to assert, "No, that must first be proved!"

This is the challenge each of us face today: to learn to let the spiritual arise from nature with the moral as a

given, as if we were children on the beach of life, as my poem inspired by Page 51 summarizes:

Children on the Beach

Let our lips be moved by Spirit,

not by decadent dogma,

Like children on the beach of life

who make castles out of sand.

Let our lips announce, "God stands there"

and declaim the call for proof

Like children on the beach of life,

kneel in churches made of sand.

Let the Spirit rise from Nature,

the moral as a given,

Like children on the beach of life

dancing gladly hand in hand.

Let our lips be moved by spirit

not by empty creeds,

Like children on the beach of life

whom the ocean feeds.

As Steiner has remarked in several other places, "Discussion begins when knowledge ends." One can

discuss things endlessly to no effect or study the knowledge of the past and learn to experience the spiritual

realities in one's present time. If we do not achieve that, we will be left with the strictures of religious dogma and

the dried remnants of moral intuitions in our so-called "conscience."

[page 52] Human beings began to "prove" the existence of the divine only when they

had lost it, when it was no longer perceived by inner, spiritual perception. The

introduction of proofs for the existence of God shows, if one looks at the facts

impartially, that direct perception of the divine had been lost. However, the moral

impulses of that time were bound up with what was divine. Moral impulses of that time

can no longer be regarded as moral impulses for today. When in the first third of the

fifteenth century the faculty of perception of the divine-spiritual in the old sense was

exhausted, perception of the moral also dried up, and all that remained was the

traditional dogma of morals, which people called "conscience."

Lacking the experience of the spiritual realities, the religious communities strove to provide their followers

rules, commandments and catechisms as replacements.

[page 53] There is a good deal of truth in certain contemporary religious philosophies

when they allude to a primal revelation preceding the historical age of Earth. External

science cannot get much beyond, shall I say, a paleontology of the soul. Just as in the

earth we find fossils, indicating an earlier form of life, so in fossilized moral ideas we find

forms pointing back to the once living, god-given moral ideas. Thus we can come to the

concept of primal revelation and say: This primal revelation dried up. Human beings lost

the ability to be conscious of the primal revelation. And this loss reached its point of

culmination in the first third of the fifteenth century. Human beings perceived nothing

anymore when they looked within themselves. They preserved only the tradition of what

they had once beheld. Religious communities gradually seized upon this tradition and

turned its externalized content, this purely traditional content, into dogmas which people

were expected merely to believe, whereas formerly they had living experience of their

truth, as coming from outside of the human being.

We have heard philosophers telling us that "God is dead" and now Steiner tells us that "Science is dead"

I wonder if people will get as nervous about Science being dead as they did over the thought that God was dead.

Here is his full statement:

[page 58] Science is dead. Science cannot make what is living flow from the mouth. And

without this, one cannot build upon it. One must appeal to an inner livingness, and so one

must really begin to seek. The divine lies precisely in the appeal to the original, moral,

spiritual intuitions. But if one has once grasped the spiritual, then one can unfold the

forces that enable one to grasp the spirit in wider spheres of cosmic existence. And that

is the straight path from moral intuitions to other spiritual contents.

What can we do if science is dead? It is not a necessary condition for science to be dead, it has only become

so by the bad habit of logical and rational thinking operating on cold, abstract concepts rather than the living

reality which surrounds every scientist if she but look. Here is a scientist who teaches people to look directly at

the living phenomena, Stephen Edelglass. His book is The Physics of Human Experience and shows us how to

deal directly with the living phenomena. It is this kind of scientific approach that Steiner talked about in this next

paragraph. If we could trace back what brought Edelglass to understand physics using the phenomenalistic

approach, we might find its origin in this very lecture given to youngsters in 1922.

[page 59] We must proceed as follows. On the one hand, we must acknowledge that

outer science by its very nature can only comprehend what is material; hence, the view

of the material must be not only materialism, but also phenomenalism. On the other, we

must work to bring life back into what has been made into dead thinking by natural

science.

Steiner warns us that with mere words, we cannot grasp the living, especially the words of dead philosophies

which have replaced real philosophies in recent centuries.

[page 59] Why is it that we no longer have any real philosophies? It is because thinking,

as I have described it, has died. When based merely upon dead thinking, philosophies

are dead from the very outset. They are not alive. And if people, like Bergson, seek

something living in philosophy, nothing comes of it, because, although they struggle for

it, they cannot lay hold of the living. To grasp the living means first to attain vision.

Here is Steiner revealing how the maturation of the individual today correlates to the maturation of the human

being over the centuries of evolution of consciousness. To get rid of dead thinking we must seek to think in the

way that youngsters below the age of fifteen think, in living concepts not bothered by the moribund intellect, which

corresponds to the way humankind thought before the fifteenth century.

[page 59] What we need to reach the living is what can be added out of what worked

within us before our fifteenth year. This, from before our fifteenth year, is not disturbed

by our intellect. We must carry what works within us, as spontaneous, living vision, over

into the dead thinking. Dead thinking must be permeated with forces of growth and with

reality. For this reason, and not out of sentimentality, I want to refer to the words from

the Bile, "Except ye become as little children, ye cannot enter the Kingdom of Heaven."

How are we to become children? Is not the boy the father of the man, the girl the mother of the woman?

Somewhere in us, submerged under an avalanche of dead thinking, is that boy and girl struggling for air, pleading

for, as Goethe did with his last breath, "More air!" If we would throw open the shutters for others, we must first

open them for ourselves, and become like "children on a beach", as my poem above urges as it expresses what

I feel as what Steiner exhorts us to do.

[page 60] . . . we must return to childhood and learn a new language. The language we

learn in the first years of childhood gradually becomes dead, because it becomes

permeated by dead intellectual concepts. We must quicken it to new life. We must find

something that strikes into what we are thinking, just as when we learned to speak, an

impulse arose in us out of the unconscious. We must seek a science that is alive. We

should consider it a matter of course that the thinking that reached its apex in the last

third of the nineteenth century silences our moral intuitions. We must learn to open our

mouth by letting our lips be moved by the spirit. Then we shall become children again,

that is to say, we shall carry childhood on into our later years. And that is what we must

do.

Most of all we should learn to treat our children as reincarnated human beings who have lived many earlier

lives and help them to uncover what their plans are for this new life upon Earth. We focus so much on un-dyingness (immortality), but neglect the aspect of un-bornness, up until now. We must learn to think of our

children, not as a chip off the old block, but as cornerstone for a new block. Remember, if there is a world-riddle

to be solved, it is the riddle of the human being which is always new and all ways evolving, never to be fully

solved, but to be lived through, one day and one night, one life in the body and one life in the spirit at a time. As

Steiner spoke it:

[page 64] Man himself, moving as a living being in the world, is the solution to the

world's riddle! Let us gaze at the Sun and experience one of the cosmic mysteries. Let

us look into our own being and know that within myself lies the solution to this cosmic

mystery. "Man, know thyself and thou knowest the world!"

There was another author I read earnestly when I was eighteen years old, Ralph Waldo Emerson, reading

especially his essays. The essay which most resonated with me, and which I have re-read many times is, "Self-Reliance." Here is a quotation from that essay which hints at the passage from Steiner which follows: "There is

a time in your education when you arrive at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that you

must take yourself for better, for worse, as your portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel

of nourishing corn can come to you but through your toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to you

to till. The power which resides in you is new in nature, and none but you know what it is, nor do you know until

you have tried." Every human has a power that is new, a power which can change our own moral intuitions,

setting the world's moral intuitions on a new course.

[page 65] But in the same way as the old moral intuitions have lived themselves out in

historical evolution, to which we were obliged to call attention yesterday, so, too, the

impulses mentioned no longer contain an impelling force for the human being that they

once had. They cannot contain it if the self-acquired moral intuitions, of which I spoke

yesterday, appear in human beings; if, in the world evolution, single individuals are

challenged, on the one hand, to find moral intuitions for themselves by dint of the labor

of their own souls, and, on the other, so awaken the inner strength, the inner impulses

to live according to these moral intuitions. And then it dawns upon us that the old moral

impulses will increasingly change, taking a different course.

Emerson and Steiner both understood individualism and supported it against the claims of those who saw

only the bad side of individualism. An individual who respects the life, thought and ideas, and possessions of

others, following Galambos' volitional science precepts, can certainly express individualism without any bad side

effects. Individualism which respects others in all ways is infused with a beneficial moral intuition and can certainly

be considered ethical.

[page 67, 68] As humanity is developing in the direction of individualism, there is no

sense in saying that ethical individualism destroys the community. It is rather a question

of seeking those forces by which human evolution can progress; this is necessary for

human evolution in the sense of ethical individualism, which can hold the community

together and fill it with real life.

Emerson also wrote about love and friendship, "We will meet as though we met not, and part as though we

parted not." We can do this with each person we meet it if we but keep in mind that each person is a "walking

world riddle." A riddle, we can only pretend to solve, but whose solution seems to drift further away the more

we learn about the person. We do best if we treat each person as an unanswered question, a walking riddle, and

hope glimpse from time to time small unfoldings of a solution, unfoldings which develop over time into confidence.

[page 68] We must meet the human being in such a way that we feel each to be a world

riddle, a walking world riddle. Then we shall learn in the presence of every human being

to unfold feelings that draw forth confidence from the depths of our soul. Confidence in

an absolutely real sense, individual, unique confidence, is the hardest to wring from the

human soul.

Steiner directs our attention to the concept he calls "responsive tiredness". Unless we work enough to

become tired, we live an unhealthy existence.

[page 73] Responsive tiredness, I call it. In ordinary life organic existence requires not

only activity but also the accompanying state of tiredness after the accomplished work.

We must not only be able to get tired, we must also from time to time be able to carry

tiredness around within us. To pass our days in such a way that we go to sleep at night

simply because it is customary to do so, is not healthy; it is certainly less healthy than

to have the due amount of tiredness in the evening and for this to lead in the normal way

into sleep. So too, the capacity to become tired-out by the phenomena meeting us in life

is something that must be.

In a contrary view to that expressed by the old saying, "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy."

Steiner tells us, in effect, "All play and no work makes a dull boy." A child educated by play will have fun, but

learn nothing from it.

[page 73] The right thing is for teachers to be able to handle what does not give the child

joy, but perhaps a good deal of toil and woe, in such a way that the child, as a matter of

course, submits to it. It is very easy to say what should be taught to the child. But

childhood can be ruined by learning being made into a game. For it is essential that we

should also be made tired in our soul by certain things; that they should cause toil and

exertion. One must express it thus, even if it sounds pedantic.

As a lesson for adults, he suggests his own cure for insomnia: work harder. He doesn't need to tell me

I learned that on my own. I have not been beset by insomnia, but there have been times when I woke up in the

middle of the night or early morning about 3 am and instead of tossing around on the bed, I simply got up and

did some work. Sometimes I worked all day, sometimes only a hour or so, but every time the experience seemed

a beneficial one to me. It helps one's sleep patterns to always have work that is waiting for your attention to fill

these occasional bouts of sleeplessness when they arise. Steiner directed his comments to the young adults in his

audience, but it would seem to apply equally as well to older adults, who need to provide their own guiding line,

while the younger get their guiding line mostly from their elders.

[page 74] . . . what permeated the young, at the turn of the nineteenth century and the

twentieth century, derived a quite special character the character of the life force in

human beings who go to bed at night, who are not tired and keep turning and twisting

about without knowing why. I do not want to imply anything derogatory, for I am not of

the opinion that these forces, which are there at night in human beings when they turn

and twist about in bed because they are not tired, are unhealthy forces. I am not calling

them unhealthy. They are quite healthy life forces, but they are not in their proper

place; and so it was, in a certain sense, with those forces that worked in the young at the

turn of the nineteenth century. They were thoroughly healthy forces, but there was

nothing to give them direction. The young had no longer the desire to apply these forces

to what was told them by their elders. Yet, forces cannot be present in the world without

being active, and so, at the time referred to, innumerable forces yearned for activity and

had no guiding line.

We meet people whose writings fire us up and others whose writings leave us completely cold. Steiner

contrasts two such writers for us, Albertus Magnus and Johann Friederich Hebart. Magnus was hot and Hebart

was icy. He uses these two writers to show how the style of thought and expression changed dramatically

between the Middle Ages of Magnus and the nineteenth century of Hebart.

[page 75, 76] When Albertus Magnus devotes himself to knowledge-something that

lights up in him or becomes dim-we feel him as it were in a fiery, luminous cloud, and if

we are gradually able to enter into such a soul, we come into this fire ourselves. Even

if for the modern soul it is antiquated, we feel that it is not a matter of indifference, when

we steep ourselves in what is moral, write it down, speak about it, or even just study it,

whether or not one is sympathetic or antipathetic toward a divine-spiritual being. This

feeling of sympathy or antipathy always plays a part.

On the other hand, if we steep ourselves in the way Herbart objectively and

scientifically discusses the five moral ideas: goodwill, perfection, benevolence, rights,

and retribution, we do not have a cloud that encircles us with warmth or cold, but

something that gradually freezes us; it is objective to the point of iciness. And that is the

mood that has crept into the whole nature of knowledge and reached its climax at the

end of the nineteenth century.

Steiner describes a society he knows very well, the Theosophical Society, which produces a lot of books

and educational material. I tried reading some of their material before I found Steiner's works, and my eyes glaze

over and I would become immediately sleepy. To me , it should have been named, the Theosoporificial Society,

for the sleep-inducing quality of its written materials.

[page 78] For what is contained in Theosophical literature is to a great extent a sleeping

potion for the soul. People were actually lulling them selves to sleep. They kept the

spirit busy, but look at the way in which they did so. By inventing the maddest

allegories! It was enough to drive a sensitive soul out of its body to listen to the

explanations given to old myths and sagas. What allegories and symbols were thought

up! Looked at from the biology of the life of soul, it was all sleeping potion. It would

really be quite good to draw a parallel between the turning and twisting in bed after

spending a day that has not been tiring and the taking of a sleeping draught in order to

cripple the real activity of the spirit.

Several years ago, I was taking a graduate course called "College Teaching" and it gave me a chance to

study and ponder the question of how teaching and learning happens in the presence of a live teacher. So much

of today's teaching takes place over the Internet or by use of recorded audio or video lectures that this question

is an important one. What is added by having the teacher present? The obvious answer is you can ask the teacher

a question if one is present, but even if you don't ask a question, what is happening that is important to learning,

which cannot happen through pre-recorded lectures? The answer I came up with was surprising to me. I came

to understand that true learning takes place directly between the teacher and the learner, in both directions, and

non verbally. It happens if the teacher has fully assimilated the material being covered and is used the words to

track through the ideas which are going on inside her head. The ideas are transferred directly to the learners' mind

and the words she used act as a way of recalling those ideas later. This is a quick summary of my insight, which

can be read in detail in my term paper, Teaching and Learning in the College Classroom. It is clearly applicable

for all levels of teaching and learning, and its implication for our methods of education are important. One cannot

depend solely upon pre-recorded lectures to accomplish education there must be live teachers present in the

classroom, and not just to answer questions, not just for discipline, but for truly deep transmission of ideas and

processes to take place.

This insight also brought me a new understanding of what happens during lesson plan preparation by a

teacher. By poring over the material in preparation for the next day's lesson, the teacher begins to form the ideas

which he will be thinking of while going through the material the next day. It is those ideas which will be

communicated using his words as a carrier wave, if you will, a carrier wave which also acts as a route to be taken

through the important ideas that need to be transmitted directly from the teacher's mind while he is talking. If a

teacher is so poorly prepared as to have to talk about material he doesn't understand, the pupil's eyes will glaze

over and their attention will be anywhere else, out the window, on a beach date for the weekend, whatever, but

no teaching or learning will take place. Enough of that happens to pupils who are not interested in the material,

but this will also happen to those who are actually interested in the material which is supposed to be covered.

Steiner gives us an example of the attitude of such students:

[page 77] They say of those teachers: "They are wanting to teach me something that

they first have to read. I should like to know why I am expected to know what they are

reading. There is no reason for me to know what they are only now reading for

themselves. They do not know it themselves, otherwise they would not need to stand

there with the book in hand. I am still very young and am expected to learn what they,

who are so much older, do not know even yet and read to me out of a book!"

It is not the book in hand that is the problem, rather it is that the teacher does not know the material, and the

students feel empty during the reading because nothing comes forth directly from the teacher's mind! In earlier

times, this kind of teaching by reading out of books would no have been tolerated. The feeling for the direct

transmission of learning received from the teacher was experienced as a fire within and was as real as anything

received by the eyes or ears of the students.

[page 81] In olden times people understood the experience of having something kindled

within them in mutual interaction with another human being. They counted somebody

else's telling them what they themselves did not know as among the things they needed

in order to be able to live. It was reckoned so emphatically as one of the factors

necessary for life that it was considered equal to perception through the eyes and the

ears.

Can we understand at all today that there are divine spiritual beings who walk through our world today,

leaving footprints on our minds which we call thoughts? I recall the wonderful question that Jane Roberts asked

about our thoughts, "Where is the tree from which fruit drops into mind's basket?" She and Seth knew about the

reality of the spiritual world from which thoughts percolate into our minds and steep into our brains(4).

[page 86] There is a divine weaving streaming around the Earth just as in the physical

world the atmosphere streams round it; and in this streaming, beings, the thoughts,

remain behind and reveal themselves to human beings. They are, so to speak, the

footprints of the divine world surrounding the Earth, which are buried in human beings

as thoughts.

Unless and until we rise out of the immured passive thinking encouraged by our times, unless and until we

enliven our thinking as befits our current incarnation on Earth, we cannot understand freedom nor develop true

freedom in our lives. The message is there in Steiner's classic work, The Philosophy of Freedom, but it requires

work by all readers to remove the insulation of passive thinking and allow the sparks of spiritual insight to infuse

and enliven their thinking.

[page 93, 94] In what I have named anthroposophy, in fact in the foreword to my

Philosophy of Freedom, you will meet with something that you will not be able to

comprehend if you give yourself up only to the passive thinking so specially loved today,

to that popular godforsaken thinking that was already godforsaken in the previous

incarnation. You will only understand it if you develop, in freedom, the inner impulse to

bring activity into your thinking. You will never get on with spiritual science if that

spark, that lightning, through which activity in thinking is awakened, does not flash up.

Through this activity, we must re-conquer the divine nature of thinking.

Steiner creates a metaphor for passive thinking: a man is lying motionless in a ditch. When asked why, he

says he doesn't want to move and even resents the Earth's forcing him to move as it revolves. This is the attitude

of an immured passive thinker, walled on all sides by passive thinkers from an early age, she resents or ignores

anyone who attempts to move her to active thinking. I have known both men and women who were passive

thinkers and had no clue as to existence of active thinking and if one attempted active thinking with them, one

would be derailed or ignored before completing a single sentence. Their entire world of thought and conversation

comprised repetitions of what they saw or heard others do or say. Passive thinkers can be very active in

conversation, but not in thought. Holding a real conversation with a passive thinker is like having a tug-of-war with

someone who won't pull the rope, only follow its tug.

[page 94] This is how people appear who do not wish to bring activity into thinking, the

power that alone can bring back, out of the human being, a connection between the

human soul and the divine-spiritual content of the world again. Many of you have

learned to despise thinking because it has met you only in its passive form. This,

however, is only head-thinking in which the heart plays no part. But try for once really

to think actively, and you will see how the heart is then engaged. Human beings of our

age enter with the greatest intensity into the spiritual world if they succeed in

developing active thinking. For through active thinking we are able to bring hearty,

courageous forces into our thinking again.

What is the meaning of the word intellectualism which Steiner uses frequently in these lectures to his young

audience? He uses the word to refer to the abstract logical way of thinking which pervades so much of extant

thought and science today. To understand how changed we have become from the ancient Greek times, one need

only read the Iliad and the Odyssey's opening words, "Speak to me, O Muse, . . ." clearly showing the words

of the two tales were coming from the spirit. Homer's epic existed for hundreds of years before being written

down, and so almost a thousand years or more could have passed before in Roman times Virgil penned his

Aeneid, which begins, "Of arms and a man I sing. . ." Clearly an evolution of consciousness had occurred

between Homer's time and Virgil's. Homer spoke the words of a Muse and Virgil wrote out of himself.

[page 96] Among the Greeks, concepts, ideas, were bestowed by the spirit. Because of

this, their intellect was not so cold, so lifeless and dry as ours is today, which is the

result of being worked out by ourselves. Intellectualism has first arisen through the

special development of the consciousness soul.

In Steiner's time, the early twentieth century, educators were already experimenting with the use of gadgets

such as calculating machines to keep the teaching as objective as possible. We have gone even further in the

ensuing ninety years, replacing live teachers with programmed instruction, classes over the internet, standardized

textbooks, lesson plans, and achievement tests, etc.

[page 100] Today when we speak of visual or object teaching, we keep the teaching

quite apart from the personality of the teacher. We drag in every possible kind of

gadget, even those dreadful calculating machines, in order that the teaching may be as

impersonal as possible. We try to separate it entirely from the personal. Such a

separation is not really possible. The endeavor to keep the teaching entirely apart from

the personal only leads to the worst sides of teachers coming into play, and their good

sides are quite unable to unfold when so much objectivity is dragged in.

How can we correct this trend to overweening objectivity? We could stop striving in education to fill a human

being with knowledge as if we were dropping coins into a piggy bank, and instead seek to understand the human

being, the full human being.