If you're an employee and your boss tells you to "Hit the road!" that is usually not a good thing, but

when Simon's boss told him that, he suggested Simon go traveling and write a book about his travels. In fiction, there are

two main plots, 1) a hero goes on a journey and 2) a stranger comes to town. Simon calls these cultural

myths and lays them out for us:

[page 1] The mysterious traveler who blows into town, the life-changing encounter with

a stranger, never forgotten, never recovered, the slow climb that reveals the

breathtaking view — we all share these cultural myths, as we trudge to work or sit

halfheartedly at the desk.

The difference between tourist and traveler, I've heard, is this: a tourist has a lot of money and little

time, a traveler has little money and a lot of time. It's hard to say which category Simon fits into because

his expenses were picked up by his boss, but his decision to avoid fast modes of transportation, walking

whenever possible, suggests him to be of the traveler mode, almost a pilgrim. I say almost because he didn't

travel alone, taking along his copy-editor, attorney wife and a couple of friends which morphs his journeys

into a Woody-Allen-type film, but with more grist and less laff. One bit of sage wisdom suggests that a

pilgrim focus on the journey more than the destination.

[page 1] The trouble is that any really serious pilgrim travels alone. You are meant to

make a journey where the very traveling leads you to explore yourself, your relation

to God, or your life or your past. The endpoint is somehow only a small part of the

process of inward transformation.

The answer to Simon's dilemma was easy: he likes to spend long hours reading, but doesn't like to eat,

drink, sleep, walk, or even be silent for long. He interjects on page 2, "I am not necessarily the person you

want to sit next to in the library." His wife was reluctant to join Simon on his travels, "You want me to be

the straight man to your pilgrim wit." And added, "I'm not taking time off for that." Simon says to one side,

"Lawyers do not think of time like you or I do. There is no place for pleasure, let alone a journey of self-discovery. Time is divided simply into billable and nonbillable hours." (Page 3) But she finally gives in to

join him on his journey, and they invite two close friends along to provide more conversation during eating,

drinking, and walking, which he expected to spend a lot of time doing. All that decided, Simon could focus

on the destinations for his journeys, places that would not leave him "gaping or aping". By aping he meant

looking like a Westerner in a sari, "sadly mimicking a longed-for mystique." (Page 3) The reasons for Simon's

averseness to gaping is spelled out in this passage:

[page 16] For me, books opened a world of the imagination, a world in the mind: why

would you want to shut the door on such a greater landscape to fixate on some merely

real place or object?

Simon opted for something which befitted his career as a college professor of Greek literature, so he

didn't aim for Agra, India where he would have to stand gaping at the Taj Mahal. It might have been an

ineffable experience for him, all fine and good, but how does one turn the ineffable into effable for one's

readers? See the problem? So, Simon says, "no gaping or aping", and when a command begins with "Simon

says", you know you have to do it.

The something Simon chose was a type of traveling, a phenomenon which first appeared in the nineteenth century, "the tour to visit

writers' homes".

[page 7, 8] The birthplace, the grave, the house where the writer lives, or even where

the writer was now living — all, for the first time, became sites of pilgrimage. The

journey was treated like a visit to a saint's shrine.

On trips, I have at times visited a writer's home: there was the garret in the wall in Prague where Franz

Kafka wrote, the small home which Anne Frank hid in and wrote, and Campobello Island off the coast of

Maine, where Franklin Delano Roosevelt spent his summers and likely placed his buttocks in the rocker and

wrote at the desk in his office, and most recently I walked through the apartment of the famous writer,

Frances Parkinson Keyes, which is off the patio of the Hermann-Grima House in New Orleans' French

Quarter.

Simon added one further fillip to his travel plans, it would be Victorian-style, the way the staff in

Downton Abby might travel on a journey.

[page 14] Like so many characters in Victorian stories, we would consult the train

timetable, wear stout shoes, and stay in the local inn.

What is a literary lion and how did that phrase come into being? Simon says we owe its existence to

a famous lion in the London Zoo, famous because it attracted thousands of visitors to its cage. When authors

became so famous as to attract thousands of readers, they were called literary lions and were said to have

been lionized thereby. There is another word usage that came into English from the London Zoo. Our

ubiquitous American word on everything from cereal boxes to sodas, JUMBO, came from a name P. T.

Barnum coined for the large elephant he donated to the London Zoo. Soon the word jumbo was used for

everything of a large size. Once during WWII, my mother wrote to her sister-in-law, Nancy, a war-bride still

living in England, giving her a recipe for gumbo. Nancy's mother, reading along with her, commented,

"Those poor people, they have to eat elephant!" It may have been a jumbo gumbo; Cajun gumbos usually

fill a large pot and feed a large family. All of which brings us to Simon and his first literary lion, Sir Walter

Scott.

In the early days of the Internet, many people likely thought, "Oh, what a tangled web we weave when

first we practice to receive" data over the voluminous World-Wide Web, and that would be a close

paraphrase of "what a tangled web we weave when first we practise to deceive" from Scott's Marmion.

Then the Google Search Engine came along to untangle the web into useful skeins of information in a few milliseconds. Scott's

famous line has remained famous, even though his literary lion status may have paled over the decades. While his Rob Roy,

The Bride of Lammermoor, Waverly, and The Heart of Midlothian are mostly forgotten and rarely read

outside the academy, Ivanhoe made a big splash at the movies and TV in the 20th Century.

Have you heard the joke where the Puritan preacher wagged his finger at a parishioner in a low cut

dress, attempting to shame her by saying, "St. Peter is wagging his finger at you!" Alas he gets the words

finger and Peter reversed. Read the next passage, quoted verbatim, and imagine Simon wagging his figure

at nonbelievers. This has become part of my collection of "creative typos" — those typos which add some humor to the text in which they appear. Perhaps his copy-editor wife was rushing to get back to her billable attorney hours? Or perhaps she laughed so much, she decided to leave it in.

[page 22] . . . Scott is the earliest of the nineteenth-century authors we will be following,

and not just because — I found myself almost wagging my figure (sic) at the non-believers — he is so important in the history of the novel and of writers' celebrity. The

house itself justifies the trip.

Scott was such a celebrity in his time that a monument was erected of him at the Waverley Railroad Station

named after his novel "Waverley". Simon asks us to imagine the equivalent scene in our time, to imagine,

perhaps, how ludicrous it would be to have a "What Man Hath Roth" statue for arriving train passengers in

New York City. Please no Complaint from any of you. As the man accused of statutory rape explained to

the judge, "Honest, Judge! If I had known she was a statue. . ."

[page 26] So, you get into New York, and arrive not at Grand Central but at Portnoy

Station, and walk down Forty-second Street into Times Square to see a huge statue and

monument to Philip Roth (designed by Andy Warhol). Dream on.

I have walked the streets of Manhattan and seen Greeley's and Washington Irving's modest statues,

modest monuments to writers, and there are probably many more such statues to writers, but none to

compare with the one to Walter Scott. Ah, yes, one could call Thomas Jefferson a writer and point to his huge

statue carved into Mount Rushmore, but there's certainly no Declaration of Independence Railroad Station

nearby, is there?

As for the eponymous Scott's Buttocks, here is the passage where Simon refers to the famous derrière,

the trousers which enclosed it, and the chair upon which it sat to write. Yes, they displayed the trousers he

wore just before his death next to his chair.

[page 32] While the chair on which the Wizard of the North had sat was treated with

awe, the trousers were somehow too close to the body of the man himself. The chair was

the receptacle of suitably clothed genius, the trousers housed something more fleshy.

The desire to feel the intimate presence of the author was amply fulfilled without such

distracting immediacy.

Clearly Abbotsford, the house of Walter Scott, is to Scotland what Graceland, the house of Elvis

Presley, is to Memphis, Tennessee: both are houses of real persons which attract many pilgrims. But what

about imaginary places such as Hogwarts of Harry Potter, or the real house used to film a fictional story?

Yes, there's a reconstruction of Hogwarts in Disneyworld. And believe it or not, the house in Cleveland,

Ohio used to film the fictional tale "A Christmas Story" (1981) has become a place of pilgrimage in recent

years.

Nothing gets off scot-free from notoriety. But that's Dred Scot, not Walter Scott. No good deed goes

unpunished, it seems.

William Wordsworth didn't get a piece of the title, but he got a sizeable piece of the book.

Unfortunately I found only one suitable quotation which summarizes the two Wordsworth places of

pilgrimage for Simon and his three companions.

[page 57] It's as if Dove Cottage is an element in a picturesque scene: the poor but

pretty cottage framed by flowers. But Rydal Mount is a stage set for the poet as the

spectator of all he surveys.

A curious note: Wordsworth was a pilgrim to Scott's home and scribbled a note there and signed it.

Now Wordsworth's two places of residence are being scribbled upon by modern scribes.

The Brontës' home Haworth is the next place of pilgrimage, and Simon, our author, is distressed by its

condition, how much its buildings have been changed in rebuilding, making it look as it did in old pictures,

but now a brand new, clean, Disneyesque reproduction, not the original buildings. He bemoans this state of

affairs, comparing it to his experience of Jerusalem. I have often wondered how authentic such sites of

pilgrimage as the Way of the Cross were, and now Simon says what I have always suspected is true.

[page 68, 69] I have spent a lot of time in Jerusalem at sites of religious pilgrimage that

are not only back-constructions but back-constructions of things that never happened

and certainly didn't happen there. I still find it weird watching pilgrims intently kissing

the ground of the route of the Stations of the Cross, when we know that the ground

Jesus walked is many feet below the current level, that most of the stations are based

on fabricated medieval stories, and that even if Jesus did go from court to crucifixion

at the site memorialized by the Church of the Holy Sepulcher this was not the route.

But I have also learned that powerful feelings aren't often swayed by academics yelling

about fakes and truth. Deriding relics and other people's sacred rites has been good

sport for centuries, but it is far more interesting to think about why we all need our

pilgrimages. Haworth isn't quite like the Stations of the Cross, but it is worth asking

why it continues to have such a pull on the imagination

His wife, copy-editor, and companion on his journeys for this book, rebuffs him, not with lawyerese

talk, but from a purely feminine perspective, with the need for every woman to have, as Virginia Woolf wrote in her famous novel, A Room of Ones Own.

[page 69] "Darling!" said my wife, with a certain exasperation, "It's girl stuff." That

must be true. Charlotte Brontë is the story of the girl who struggled to find a voice, who

epitomizes the difficulties of becoming a writer as a woman, then, of course, but still

now. Haworth stands for every woman's home, the repression of the inner self in social

propriety — and Charlotte's need to use a man's name to publish at first demonstrates

the social constraints against which she fights, just as Jane Eyre is the story of a girl's

journey into self-assertion, a pilgrimage in itself. Haworth is the symbol of a woman's

struggle for self-expression.

Simon says going to Haworth felt to him like joining a cult, a condition much fostered by Winifred

Gérin's biography of the four Brontë children and of Mrs. Gaskell, the first Brontë biographer.

[page 71] The fascination with the Brontës bites deep and leads the biographer to walk

in every footstep, to collect every discarded tchotchke as a relic (Anne's teapot is a

"silent witness" to her true character! I ask you . . .), and to believe that you can get to

their inner world by living where they lived. The only other place you see language like

this is with religious pilgrims. At this level, going to Haworth feels like joining a cult.

In one light moment, Simon says that in a time when the outdoor privy (outhouse) was normal, Haworth

had a two-seater. My grandmother had a two-seater when I was a pre-teen and the idea of using it for

applying makeup or long conversations would have never occurred to any user of the facility, alone or not.

But perhaps Victorian Britain had a less acute sense of smell. . . .

[page 75] It opened up visions of Anne and Emily taking their makeup and going out

together for a gossip and a pee. Haworth lightened up.

Another light moment comes with the curious contiguity of death and laundry — it seems that the

washer women of Haworth used the tall headstones of the nearby graves to hang their laundry upon to dry.

This seems imminently practical to me, the stones are constantly wet by the rain, why not by damp

clothes hanging to dry? Beats hanging the clothes on a line held up by a clothes pole as we did back in the

pioneer days of the 1940s before automatic gas and electric dryers became ubiquitous in every home. But

Reverend Nichols, later Charlotte's husband, angrily stopped that practice.

[page 76] There is something touchingly fitting to the painful banality of Victorian

working life in the earnest curate's anger at the washerwomen's earthy combination

of death and laundry.

On page 81 Simon says after leaving Haworth that the Brontë myth "works best when it takes up

residence in the imagination". Imagine that! Why? Because the physical residence has been purified and

sanitized to suit a museum curator more than earnest pilgrims hoping to find the place the Brontës created

in their imagination.

[page 80] In the parsonage, nothing can be touched — and nothing was particularly

touching. It was all too clean. The real behind glass. Without any grit, without the feel

of such materiality, the house had lost its soul as a lived-in space.

Simon's next trip was to Stratford-on-Avon to visit Shakespeare's House which remained a pub, a

public house until the 1950s when it was restored, looking afterward "so smug and so new. . . It had been

'restored,' a word to strike terror into the heart of an antiquary, not to mention a man of taste," by John

Mounteney Jephson (1863), as the note under the photo on page 97 remarks. One can compare it newness

to its authentic pub facade in 1850 on the facing page 96. The restoration stripped Shakespeare's office bare

except for a desk, but the 1850s office was full of stuff, books, and even busts of Shakespeare himself. One

can imagine Will telling someone, "I want a bust of myself to put in my office." But clearly these busts were

cast long after Will's death and placed there by someone else.

Simons says, rather asks, about the preservation of historic buildings, "Should an old building be

allowed to fall away, naturally, as Ruskin demanded? Should it be rebuilt according to an original plan?

Preserved as a ruin? Redesigned according to modern taste?" My home city of New Orleans, founded nearly

three hundred years ago, has dealt with preserving its French Quarter quite well, I think. One can enter Jean

Lafitte's original Blacksmith shop and enjoy a Sazerac at the bar while a Saints NFL game is on TV. Its outside

still leans a bit, but the shop retains its original size, facade, colors and shape and will not be allowed fall

down. There is a man who specializes in the original colors used during various periods of construction on

the exteriors of buildings and one must consult with him before re-painting the outside of your home. Vieux

Carre (Old Square) Commission enforces any architectural modifications. Changing an outdoor lean-to patio

cover into an indoor office is possible, but must be approved first by the Commission. We have a friend who

managed the feat, and was quite proud of his accomplishment. The French Quarter with its narrow streets

supports a vibrant community of residents from artists to ordinary people who wish to live in an

extraordinary place where every day there's a party or parade going on only a few steps away. And no one

needs a car to get around. The Pontabla Apartments are almost nearly 300 years old and still provide a prime

place to live and work above the ground-level shops. On foot one can visit homes of Tennessee Williams,

Frances Parkinson Keyes, Edgar Degas, and many other authors and artists who called the French Quarter

home. Only a few blocks away are located the home of our beloved cornet player and singer Louis Armstrong and

the tomb of Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau. The preservation societies begun in Victorian times will find a kindred spirit in the Vieux Carre Commission which ensures that there will always be an authentic French

Quarter for people of all kinds to visit and enjoy.

Freud's house on Maresfield Gardens was a familiar spot to Simon Goldhill when he was growing up.

[page 107] When I grew up around Maresfield Gardens, there were plenty of elderly

German-speaking men and women around, part of the soundscape of the city. The was

a famous café on the corner of the main road where you could get coffee and strudel,

and, if you were old and German, sit all day and talk about die Heimat, the home

country.

Freud's office, when he moved from Berlin to London, was reconstructed exactly as it was, full of

antiquities, mostly small items which might catch the eye of a patient coming into the office or reclining on

the couch, which Freud would notice and include in his observation and shaping of the analytical session

with the patient. Walter Scott's slogan, an anagram of his name: "Safe behind walls", is emblazoned on a

sign at his baronial estate. At Freud's Maresfield Gardens home, where his desk resides in a room full of the

artifacts of a "middle child, pushy Jew, overintellectual, North Londoner" as Simon's lawyer wife began her

description of Freud, one might slip in a few extra words for Freud's sign, "Safe behind walls in one's

orifice."

As the last chapter of this book, it includes a wonderful summary of Simon's peripatetic journey with

his wife and friends through the homes and estates of literary lions.

[page 105, 106] Yet Freud's house fulfills the trajectory of this book perfectly, the icon

at the end of a thematic journey. Shakespeare's birthplace was invented to give voice

to a national identity, a truly English selfhood. The parsonage at Haworth in its

moorland setting became a physical expression of the interiority of the self — a new

sense of the passions and sensitivities swelling inside a woman in a restrictive and

restricted social world. Wordsworth's cottages in the lakeside landscape are treated as

a route to rediscover his journey into the self through memory, self-exploration, and

friendship — the Romantic psyche. Scott's house was built as an embodiment of his

baronial self-projection — as his novels and poems created a fictional world through

which readers found themselves through the work of the imagination. All of our writers

so far have been important for the Victorian reader precisely because they offered new

articulations of the self, new journeys of self-discovery, new ways of finding oneself

through words and the imagination. . . . Freud, too, opened pathways into the life of the

mind, through which the reader's self-awareness was fundamentally altered.

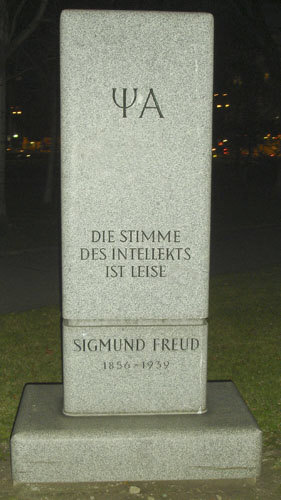

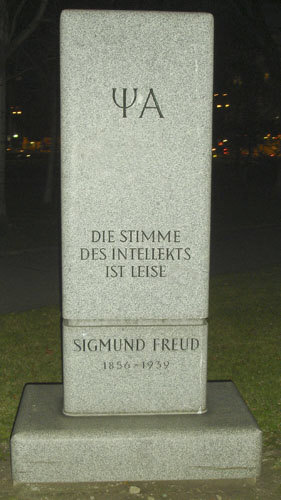

In Vienna, Austria one can view a stone cenotaph to Sigmund Freud which reads, "Die Stimme des Intellekts ist leise" which I translate as "The voice of the intellect is stilled". But as we can attest, dear Readers, the voice of a writer is never stilled.

~^~

Any questions about this review, Contact: Bobby Matherne

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

22+ Million Good Readers have Liked Us

22,454,155

as of November 7, 2019

Mo-to-Date Daily Ave 5,528

Readers

For Monthly DIGESTWORLD Email Reminder:

Subscribe! You'll Like Us, Too!

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

Click Left Photo for List of All ARJ2 Reviews Click Right Bookcover for Next Review in List

Did you Enjoy this Webpage?

Subscribe to the Good Mountain Press Digest: Click Here!

CLICK ON FLAGS TO OPEN OUR FIRST-AID KIT.

All the tools you need for a simple Speed Trace IN ONE PLACE. Do you feel like you're swimming against a strong current in your life? Are you fearful? Are you seeing red? Very angry? Anxious? Feel down or upset by everyday occurrences? Plagued by chronic discomforts like migraine headaches? Have seasickness on cruises? Have butterflies when you get up to speak? Learn to use this simple 21st Century memory technique. Remove these unwanted physical body states, and even more, without surgery, drugs, or psychotherapy, and best of all: without charge to you.

Simply CLICK AND OPEN the

FIRST-AID KIT.

Counselor? Visit the Counselor's Corner for Suggestions on Incorporating Doyletics in Your Work.

All material on this webpage Copyright 2019 by Bobby Matherne