Sacks wanted to be an experimental researcher in the field of neurological diseases and got on the

track of lipids in the myelin sheath which he spent ten months accumulating from earthworms to get a

decent size sample. He wrote, "I felt like Marie Curie processing her tons of pitchblende to obtain a

decigram of pure radium." (Page 116) His bosses could overlook the crumbs on his workbench and even

in one of the centrifuges, but when he lost all his collected myelin sample, he was done for, or rather

destined for becoming a clinical physician instead of a researcher.

Eventually Sacks found his own unique way of doing what he loved most:

"talking, reading, and writing." (Footnote Page 137).

One time Sacks had a landlady with a case of a rare disease, scleroderma, which is a very slowly

progressing illness. When his skin began changing color and spots began forming Sacks called Carol, a

fellow intern with him back at UCLA, in a panic thinking he had come down with a case of acute scleroderma. She came

with her black bag in hand and diagnosed him immediately, saying, "Oliver, you idiot, you've got chicken

pox." Oliver apparently never had chicken pox before and it was not likely he had just been exposed to

it as an adult, so Carol probed him.

The story of Arnold P. Friedman who ran the migraine clinic where Sacks did a lot of work is

interesting on several levels. He was very friendly and paid Sacks more for his work there than other places

did, even introducing him to his daughter, as a potential suitor. Suddenly Friedman grew very angry when

Sacks showed him the book on migraines that he had written, even threatening him if he ever published

his book. Sacks saw his manuscript being photocopied by Friedman's clerk, and didn't think much of it,

until after Sacks' Migraine was published and Sacks got letters from his colleagues asking if he had

published earlier versions of the manuscript under the pseudonym, A. P. Friedman. Clearly Friedman was

a primary thief who thought because Sacks did work at his clinic, that gave him the right to all of Sacks'

thoughts and writings about migraine(2)

Sacks recognized the deadly aspect of Friedman's primary theft

and Friedman's lesser talent. Primary thieves, like secondary thieves, are rarely innovative, using time-honored methods of taking what is not theirs from its proper owner. "Delusions of ownership" affects both

primary and secondary thieves, does it not? It is their very unoriginal justification for taking as their own

property something which clearly does not belong to them.

[page 158] I think Friedman had delusions of ownership, a feeling that not only did

he own the whole subject of migraine but that he owned the clinic and everyone who

worked there and was therefore entitled to appropriate their thoughts and their

work. This painful story — painful on both sides — is not an uncommon one: an

older man, a father figure, and his youthful son-in-science find their roles reversed

when the son starts to outshine the father. This happened with Humphry Davy and

Michael Faraday — Davy first giving every encouragement to Faraday then trying

to block his career. I am no Faraday, and Friedman was no Davy, but I think the

same deadly dynamic was at work, at a much humbler level.

What a moral man does is this: he gives unabashed credit and shows gratitude to a person whose

ideas helped shape his own original work. Sacks does exactly that in this next passage.

[page 179] In 1968, I read Luria's Mind of a Mnemonist. I read the first thirty pages

thinking it was a novel. But then I realized that it was in fact a case history — the

deepest and most detailed case history I had ever read, a case history with the

dramatic power, the feeling, and the structure of a novel.

Luria had achieved international renown as the founder of neuropsychology.

But he believed his richly human case histories were no less important than his great

neuropsychological treatises. Luria's endeavor — to combine the classical and the

romantic, science and storytelling — became my own, and his "little book" as he

always called it (The Mind of a Mnemonist is only a hundred and sixty small pages),

altered the focus and direction of my life, by serving as an exemplar not only for

Awakenings but for everything else I was to write.

Another way Sacks showed respect and gratitude for the innovators in his field is that he

recommended their works to his students. One such student from forty years earlier, Jonathan Kurtis,

visited Sacks recently and told him "the only thing he remembered from his medical student days was the

three-month period he spent" with him. Sacks would have Jonathan visit a patient with the illness being

studied, spend hours in the room, and give him a full report when he returned to Sacks. (Page 182)

[page 182] We would discuss the patient and the "condition"in more general terms,

and then I would suggest further reading; Jonathan was struck by the fact that I

would often recommend original (often nineteenth century) accounts. No one else in

medical school, Jonathan said, ever suggested that he read such accounts; they were

dismissed, if mentioned at all, as "old stuff," obsolete, irrelevant, of no use or interest

to anyone but a historian.

To a respecter of primary property, those original accounts are pure gold because reading them allows

one access to the originator's thoughts which often provides invaluable insights. Besides that it give one

the opportunity to show gratitude to the originators and give them credit for their great works, two

essentials that are often glossed-over in the rush of modern day life. Sacks even gives credit to the Ibsen

play, When We Dead Awaken, for inspiring the title of his own book, Awakenings. It appears in a footnote

on page 194. Footnotes are the way people credit the source of their inspirations, and people who don't

write or read footnotes often reveal themselves to have "delusions of ownership" which they prefer, like

A. P. Friedman, to keep to themselves.

A good friend of Oliver was Wystan H. Auden and when Auden headed back to England for the last

time, Oliver and Orlan Fox went to help him pack up his stuff and drive him to the airport. It was a

poignant goodbye to the USA for Auden and for Oliver and Orlan to their friend and colleague.

[page 199] We arrived early, then, and whiled away the hours in a meandering

conversation; it was only later, when he left, that I realized that all the amblings and

meanderings returned to one point: that the focus of the conversation was farewell

— to us, to those thirty-three years, half of his life, which he had spent in the United

States (he used to call himself a transatlantic Goethe, only half-jokingly). Just before

the call for the plane, a complete stranger came up and stuttered, "You must be Mr.

Auden. . . . We have been honored to have you in our country, sir. You'll always be

welcome back here as an honored guest — and a friend." He stuck out his hand,

saying, "Good-bye, Mr. Auden, God bless you for everything!" and Wystan shook

it with great cordiality. He was much moved; there were tears in his eyes. I turned

to Wystan and asked whether such encounters were common.

"Common," he said, "but never common. There is a genuine love in these

casual encounters." As the decorous stranger discreetly retired, I asked Wystan how

he experienced the world, whether he thought of it as being a very small or very large

place.

"Neither," he replied. "Neither large nor small. Cozy, cozy." He added in an

undertone, "Like home."

He said nothing more; there was no more to be said. The loud impersonal call

blared out, and he hurried to the boarding gate. At the gate, he turned and kissed us

both — the kiss of a godfather embracing his godsons, a kiss of benediction and

farewell. He suddenly looked terribly old and frail but as nobly formal as a Gothic

cathedral.

On his fortieth birthday Oliver met a man who was a student at Harvard on this way home shortly

after his first visit to England. He was to be what Oliver called a "perfect present". Oliver had been set

up on arranged dates with women, but never had sex with them. It took him getting falling down drunk

to have his first sexual encounter with a man who lifted the zonked out Sacks up off the street and carried

him to a nearby flat and had sex with him while he was unconscious. Over two decades he had several

love affairs, but always discreetly. He did not want to be alone on his birthday this year. So when this new

friend invited him a nearby apartment, he accepted.

[page 203] I did so, happily, without my usual cargo of inhibitions and fears —

happy that he was so nice looking, that he had taken the initiative, that he was so

direct and straightforward, happy, too, that it was my birthday and that I could

regard him, our meeting, as the perfect birthday present.

We went to his flat, made love, lunched, went to the Tate in the afternoon, to

the Wigmore Hall in the evening, and then back to bed.

We had a joyous week together — the days full, the nights intimate, a happy,

festive, loving week — before he had to return to the States. There were no deep or

agonized feelings; we liked each other, we enjoyed ourselves, and we parted without

pain or promises when our week was up.

It was just as well that I had no foreknowledge of the future, for after that

sweet birthday fling I was to have no sex for the next thirty-five years.

He relates this detail from his fall off a cliff while running away from a bull on a remote mountain

trail in Norway. Note how he becomes a doctor examining himself as if he were a patient.

[page 215] One can have dissociations in times of extremity. My first thought was

that someone, someone I knew, had had an accident, a bad accident, and only then

did I realize that I was that someone. I tried to stand up, but the leg gave way like a

strand of spaghetti, completely limp. I examined the leg — very professionally,

imagining that I was an orthopedist demonstrating an injury to a class of students:

"You see the quadriceps tendon has torn off completely, the patella can be flipped

to and fro, the knee can be dislocated backwards: so." With that, I yelled. "This

causes the patient to yell," I added, and then again came back to the realization that

I was not a professor demonstrating an injured patient; I was the injured person. I

had been using an umbrella as a walking stick, and now, snapping off the handle, I

splinted the stem of the umbrella to my leg using strips of cloth I tore from my

anorak and started my descent, levering myself down with my arms. At first I did so

very quietly, because I thought the bull might still be in the vicinity.

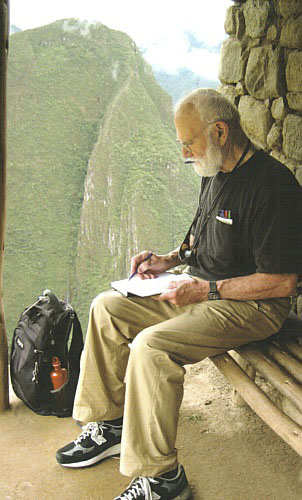

Oliver Sacks was a doctor without a formal job, but he visited patients in nursing homes all over the

boroughs of New York City as a "peripatetic neurologist" which allowed him to do his three favorite things,

"talking, reading, and writing".

When a former mentor in neurology at UCLA visited in New York, he asked Oliver about his work

and exclaimed, "But you have no position!"

[page 222] I said I did have a position.

"What? What sort of position do you have?" he asked (he himself had

recently ascended to chair of neurology at UCLA).

"At the heart of medicine," I answered him. "That's where I am."

Oliver was a doctor of the brain and the heart, and he brought heart into everything he did and wrote

his heart out upon the pages he gave to the world to read. The conditions he encountered in the nursing

homes, the so-called manors, in New York City, tore at his heart.

[page 223] In some of these places, generically referred to as "the manors," I saw the

complete subjugation of the human to medical arrogance and technology. In some

cases, the negligence was willful and criminal — patients left unattended for hours

or even abused physically or mentally. In one "manor," I found a patient with a

broken hip, in intense pain, ignored by the staff and lying in a pool of urine. I

worked in other nursing homes where there was no negligence but nothing beyond

basic medical care. That those who entered such nursing homes needed meaning — a

life, an identity, dignity, self-respect, a degree of autonomy — was ignored or

bypassed; "care" was purely mechanical and medical.

But he found hope in the places run by the Little Sisters of the Poor. He knew of their places as a boy in London,

as his parents consulted in them. His Auntie Len would tell him, "If I get a stroke, Oliver, or get disabled,

get me to the Little Sisters; they have the best care in the world." (Page 224)

[page 225] Though I was dispirited by the "manors" and soon stopped going to them,

the Little Sisters inspire me, and I love going to their residences, I have been going

to some of them, now, for over forty years.

While working on the final stages of A Leg to Stand On, Oliver got out of his car, slipped on some

black ice and laid flat on his back. The attendant came up to him and asked what he was doing.

"Sunbathing", Oliver replied. The attendant asked again, and this time he said, "I've broken an arm and

a leg." When Colin, to whom he had finally turned over the job of publishing the book, heard he was in the

hospital, he came to him and said, "Oliver! You'd do anything for a footnote." (Pages 239, 240) Here was

the accident he had been fearing he would have if he didn't get his book completed.

In the science of doyletics we postulate that doylic memories aka procedural memories are created

primarily during the pre-five-year-old stage of human development. During this phase the hippocampus

and cortex are reaching critical mass, and after that stage, all events are transmitted to the cortex by the

hippocampus as cognitive memory aka declarative memory. Speech and gestures both require storage in

doylic memory for rapid recall. Language learned after five years old is difficult, especially the unique

phonemes of a new language. For me, the T-sound at the beginning of

Zeit or Zauber, e.g., in German

is difficult as I learned the language at age 18 in college and didn't hear it as a child, even though

my Matherne ancestors came here from Germany speaking it several centuries before I was born. I can say Zauber fine if I prepare for it, but it requires a tad of my consciousness, some cortical processing for me to speak a phoneme that a native German acquires unconsciously by age five in doylic memory. Sacks explains how critical this pre-five period is in development.

[page 269] Deaf, signing parents will "babble" to their infants in sign, just as hearing

parents do orally; this is how the child learns language, in a dialogic fashion. The

infant's brain is especially attuned to learning language in the first three or four

years, whether this is an oral language or a signed one. But if a child learns no

language at all during the critical period, language acquisition may be extremely

difficult later. Thus a deaf child of deaf parents will grow up "speaking" sign, but

a deaf child of hearing parents often grows up with no real language at all, unless he

is exposed early to a signing community.

For many of the children I saw with Isabelle at a school for the deaf in the

Bronx, learning lip-reading and spoken language had demanded a huge cognitive

effort, a labor of many years; even then, their language comprehension and use was

often far below normal. I saw how disastrous the cognitive and social effects of not

achieving competent, fluent language could be (Isabelle had published a detailed

study of this).

After a visit to him, Oliver's friend in San Francisco wrote him in a letter, "I have thought about what

you said of anecdote and narrative. I think we all live in a swirl of anecdotes." That wonderful

phonological ambiguous phrase "live in a swirl of anecdotes" inspired me to write this poem:

Inspired by Thom Gunn's "swirl of anecdotes" on page 272, and Sack's comments on 273.

This World of Anecdotes

The swirl of anecdotes

within which we compose ourselves —

A digital selfie machine

we use to capture ourselves

as this world photo-bombs us.

For what are we

without this world,

without the swirl of anecdotes

we find ourselves within?

Do you want chocolate or vanilla?

"Give me the swirl!

What is life without the swirl?"

Do you write books or poems?

"To me books are vanilla,

poems are chocolate.

I like the swirl —

I find myself in the swirl."

Do you write continuously?

"I write in fits and starts —

of light and dark,

Vanilla and chocolate,

I like the swirl."

Oh, like the Quick and the Dead?

"Yes, smooth like Breyer's 'Vanilla Bean'

or with chunks and cherries

like Ben & Jerry's

'Cherry Garcia'."

Those two make a luscious world, don't they?

"A luscious swirl, in deed!"

~^~

Oliver wrote that Thom Gunn rarely reviewed what he didn't like, something that I have found true

of myself. Any book which has a scintilla of insight or delight will get a review from me. Others, the

occasional book foisted on me by a well-meaning friend, will be so outside my range of enjoyment that

I will throw the book away rather than say something bad about it which might trigger someone else to

want to read the book, thinking, "Oh, it can't be that bad!"

Thom Gunn's poem "On the Move" must have inspired the author or his publisher to use the phrase

to describe a book on Oliver Sacks' life. The words below Oliver wrote about Thom undoubtedly equally

well apply to himself.

[page 278, 279] In "On the Move," which Thom wrote in his twenties, are the lines

At worst, one is in motion; and at best,

Reaching no absolute, in which to rest,

One is always nearer by not keeping still.

Thom was still on the move, still full of energy, in his seventies. When I last

saw him, in November of 2003, he seemed more intense, not less intense, than the

young man of forty years earlier. . . . He had, so far as I could judge, no thoughts of

slowing down or stopping. I think he was moving forward, on the move, till the very

minute he died.

Oliver had some famous relatives, among them two cousins, Abba Eban of Israel fame, and Al Capp

of Dogpatch fame. I read Li'l Abner in the comics daily for decades and wondered what happened to Al

Capp to cause him to stop drawing the cartoon. Rumors about sexscapades with college girls did him in,

apparently. Oliver writes about his cousin Capp.

[page 292] There was a scandal, and Al was fired by the hundreds of syndicated

papers that he had worked for all his life. Suddenly the beloved cartoonist who had

created Dogpatch and the Schmoo, who was in some ways the graphic Dickens of

America, found himself reviled and out of a job. . . . He remained depressed, and

in declining health, until his death in 1979.

In a story about his cousin Aubrey aka Abba Eban, Oliver writes of Aubrey's visit to Einstein in his

home in Princeton. Asked by Albert if he'd like some coffee, Aubrey said yes, and Albert proceeded to

make coffee for him. "This showed the human and endearing side of the world's greatest genius," Abba

related to Oliver.

Carl Jung once wrote that "nothing so drives a man in his career than what his father almost, but

never quite did in his own life." Oliver experienced that drive from his father who had considered a career

in neurology.

[page 313] At one time, my father had thought of a career in neurology but then

decided that general practice would be "more real," "more fun," because it would

bring him into deeper contact with people and their lives.

In the last years of his life Oliver Sacks had a melanoma in the back of an eye, which was controlled

by radiation, and he experienced intense pain from knee surgery which required him to stand up for

reading and for writing. He said, "The concentration involved in writing, I found, was almost as good as

the morphine and had no side effects. I hated lying in bed, in a hell of pain, and spent as many hours as

I could writing at my improvised standing desk." We can choose to remember the man who was always

on the move spending his last years standing, writing his way into the future and into our hearts.

~^~

BOOKS by OLIVER SACKS

Click to Read Review

1. The Island of the Colorblind

2. Uncle Tungsten — Memories of a Chemical Boyhood

3. Musicophilia — Tales of Music and the Brain

4. An Anthropologist on Mars — Seven Paradoxical Tales

5. On the Move — A Life

6. A Leg To Stand On — A Neurography

7. Gratitude

8. The Mind's Eye

To Be Reviewed

9. Seeing Voices — A Journey into the World of the Deaf

10.

Awakenings — A newly revised edition of the medical Classic

11. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat — A Collection of Neurographies

12. Migraine

13. Hallucinations

14. Oaxaca Journal

------------- Footnotes -------------

Footnote 1.

Since a child under five can catch chicken pox from a person with shingles and later in life have shingles as a mature adult, we can posit that shingles is contagious, but only over a long period of time. While an adult can catch chicken pox from someone with shingles, that adult will not ever have shingles after the bout of chicken pox because the healing states are not stored as a doylic memory if the person is over five years old. The science of doyletics explains why adults cannot catch shingles from someone with shingles.