Someone called this book the story of Death, and maybe it is so, Axel writes, after all, he has been

wrestling with Death for so long, his companion at the bedside during the plague of cholera in Naples

as a young man when he watched, administered what he could, and waited as so many died. He

personified Death, talked to him, and drew comfort from his presence at times when he was alone but

for him, with otherwise only the dying for company.

[page ii] I have been wrestling so long with my grim colleague; always defeated

I have seen him slay one by one all those I have tried to save. I have had a few

of them in mind in this book as I saw them live, as I saw them suffer, as I saw

them lie down to die. It was all that I could do for them.

But Axel had lots of company in his long life, as a reader of his book will discover. In the Preface,

he imagines seeing them active in Heaven in ways similar to how he saw them when they were alive in

his world. None so prominent as the Italian postman, a female letter carrier who climbed from Capri

to Anacapri every day to deliver letters to Axel and the few other people in the small town. They

provide a perspective of his life in a nutshell, a chance to know all about Axel Munthe before reading

the book — these were the people who loved the good Dr. Munthe, among many others.

[page ii, iii] They were all humble people, no marble crosses stand on their

graves, many of them were already forgotten long before they died. They are

all right now. Old Maria Porta Lettere, who climbed the 777 Phoenician steps

for thirty years on her naked feet with my letters, is now carrying the post in

Heaven, where dear old Pacciale sits smoking his pipe of peace, still looking

out over the infinite sea as he used to do from the pergola of San Michele, and

where my friend Archangelo Fusco, the street-sweeper in Quartier

Montparnasse, is still sweeping the stardust from the golden floor. Down the

stately peristyle of lapis lazuli columns struts briskly little Monsieur Alphonse,

the doyen of the Little Sisters of the Poor, in the Pittsburgh millionaire's brand

new frock coat, solemnly raising his beloved top hat to every saint he meets,

as he used to do to all my friends when he drove down the Corso in my

victoria. John, the blue-eyed little boy who never smiled, is now playing lustily

with lots of other happy children in the old nursery of the Bambino. He has

learnt to smile at last. The whole room is full of flowers, singing birds are flying

in and out through the open windows, now and then the Madonna looks in to

see that the children have all they want. John's mother, who nursed him so

tenderly in venue des Villiers, is still down here. I saw her the other day. Poor

Flopette, the harlot, looks ten years younger than when I saw her in the night-café on the boulevard; very tidy and neat in her white dress, she is now second

housemaid to Mary Magdalen.

Axel went back to the Latin Quarter in Paris, working to complete his medical studies, learning to

"handle the sharp edged weapons of surgery, to fight on more equal terms the implacable Foe, who,

scythe in hand, wandered His rounds in the wards, always ready to slay, always at hand any hour of

the day or of the night." (Page 23) By the time chestnuts were in bloom, he had become the youngest

M. D. ever in France.

His youth did not serve him well at first, as he needed to intern in the real world and to find out

that what was wrong with people was not so important as what he told them was wrong with them. In this

next passage we catch our glimpse of his sense of humor. His private practice opened him to a set of

people that he had never met in the hospital as an intern. There were people who came in with a laundry

list of complaints and didn't want the diagnosis to be something trivial.

[page 32] They seemed quite upset when I told them that they looked rather

well and their complexion was good, but they rallied rapidly when I added that

their tongue looked rather bad — as seemed generally to be the case. My

diagnosis, in most of these cases was over-eating, too many cakes or sweets

during the day or too heavy dinners at night. It was probably the most correct

diagnosis I ever made in those days, but it met with no success. Nobody wanted

to hear anything more about it, nobody liked it. What they all liked was

appendicitis. Appendicitis was just then much in demand among better-class

people on the look-out for a complaint. All the nervous ladies had got it on the

brain if not in the abdomen, thrived on it beautifully, and so did their medical

advisers. So I drifted gradually into appendicitis and treated a great number of

such cases with varied success. But when the rumor began to circulate that the

American surgeons had started on a campaign to cut out every appendix in the

United States, my cases of appendicitis began to fall off in an alarming way.

Cutting out an appendix! That would never do for these patients. As one doctor said, "I never

heard such nonsense! Why, there is nothing wrong with their appendices, I ought to know, I who have

to examine them twice a week. I am dead against it." Dr. Axel was learning about human nature, and

being paid well by the volunteers who showed up at his office to be examined.

[page 33] It soon became evident that appendicitis was on its last legs, and that

a new complaint had to be discovered to meet the general demand. The Faculty

was up to the mark, a new disease was dumped on the market, a new word was

coined, a gold coin indeed, C O L I T I S! It was a neat complaint, safe from the

surgeon's knife, always at hand when wanted, suitable to everybody's taste.

Nobody knew when it came, nobody knew when it went away. I knew that

several of my far-sighted colleagues had already tried it on their patients with

great success, but so far my luck had been against me.

When a young Countess came to him positive that she had appendicitis and Dr. Axel assured

her it was not. She sobbed when told that, wanting to know what it was. He told her to be brave and

to stay calm and revealed to her reluctantly that it was colitis.

[page 34] Colitis! That is exactly what I always thought! I am sure you are

right! Colitis! Tell me what is colitis?" I took good care to avoid that question,

for I did not know it myself, nor did anybody else in those days. But I told her

it lasted long and was difficult to cure, and I was right there. The Countess

smiled amiably at me. And her husband who said it was nothing but nerves!

The cure required she return to the good doctor twice a week, but that was not soon enough for

her as she returned the very next day. Axel was stunned by the change in her appearance, so cheerful

and bright, and asked what she wanted. Well, she wanted to know if colitis was catching. Seems like

she was concerned about her husband and wanted the good doctor to tell him it was safer if they do

not sleep in the same room. Soon, Axel was able to report that the twice a week sessions were doing

her good. "It was evident that colitis suited her better than appendicitis, her face had lost its languid

pallor and her big eyes sparkled with youth." (Page 40)

[page 50] What is confidence? Where does it come from, from the head or from

the heart? Does it derive from the upper strata of our mentality or is it a

mighty tree of knowledge of good and evil with roots springing from the very

depths of our being? Through what channels does it communicate with others?

Is it visible in the eye, is it audible in the spoken word? I do not know, I only

know that it cannot be acquired by book-reading, nor by the bed-side of our

patients. It is a magic gift granted by birth-right to one man and denied to

another. The doctor who possesses this gift can almost raise the dead. The

doctor who does not possess it will have to submit to the calling-in of a

colleague for consultation in a case of measles.

This last note about measles caused me to chuckle as I recalled the day when I noticed my internist

in a hallway outside of the consultation room where I sat waiting for him to return with his diagnosis for

my strange symptoms. I was thirty-five at that time, had been bed-ridden for most of a week, and my

regular doctor had sent me to this internist for a consultation. Not only could he not yet tell me what was

wrong with me, but he had brought in a fellow internist and the two of them were looking up something

in the large medical dictionary in full sight of me! ! ! I trembled as he returned to explain to me what was

wrong. "Don't worry," he said, "it's just that it's not often we get a case of red measles in an adult."

Me, who had red measles as a young boy, confirmed by my mother who raised five boys and a girl and

ought to know, with red measles! Sure enough, the flood of the measles symptoms came back to me

and they matched exactly the strange symptoms I had been experiencing, fever, red spots on my body,

my eyes sensitive to light.

This next passage reveals how Axel Munthe talked to animals, this time to a Polar Bear in a zoo,

likely one from his own native land of Sweden.

[page 53] And Ivan, the big Polar Bear at the Jardin des Plantes, did he not

clamber out of his tub of water as soon as he saw me, to come to the bars of his

prison and standing erect on his hind legs put his black nose just in front of

mine and take the fish from my hand in the most friendly manner? The keeper

said he did it with nobody else, no doubt he looked upon me as a sort of

compatriot. Don't say it was the fish and not the hand, for when I had nothing

to offer him he still stood there in the same position as long as I had time to

remain, looking steadfastly at me with his shining black eyes under their white

eye-lashes and sniffing at my hand. Of course we spoke in Swedish, with a sort

of Polar accent I picked up from him. I am sure he understood every word I

said when I told him, in a low monotonous voice how sorry I was for him and

that when I was a boy I had seen two of his kinsmen swimming close to our

boat amongst floating ice blocks in the land of our birth.

In a wonderful paean to dogs, Axel explains the dog's nature better than anyone else I have

encountered. My own dog, Steiner, a Schnauzer, when I am in a hurry walking around the yard, is in

my way, seeming to know ahead of time where I am heading and managing to be there before me,

indicating a type of prescience that has always amazed me.

[page 59, 60] A dog gladly admits the superiority of his master over himself,

accepts his judgment as final, but, contrary to what many dog-lovers believe,

he does not consider himself as a slave. His submission is voluntary and he

expects his own small rights to be respected. He looks upon his master as his

king, almost as his god, he expects his god to be severe if need be, but he

expects him to be just. He knows that his god can read his thoughts and he knows

it is no good to try to conceal them. Can he read the thoughts of his god? Most

certainly he can. . . He knows by instinct when he is not wanted, lies quite

still for hours when his king is hard at work as kings often are, or at least ought

to be. But when his king is sad and worried he knows that his time has come

and he creeps up and lays his head on his lap. Don't worry! Never mind if they

all abandon you, I am here to replace all your friends and to fight all your

enemies! Come along and let us go for a walk and forget all about it.

Like Axel, I have never taught my dogs any tricks. He says, "Personally, I have never taught my

dogs any sort of tricks, although I admit that many dogs, their lesson once learned, take great pleasure

in showing off their tricks." (Page 63) Often it has occurred to me that what is called a dog trick is

actually a trick which the dog has taught the master and to which the master submits openly upon any request

of the dog, usually pointing carefully to how well the dog accomplishes his wishes and blithely ignoring

how well he carries out the dog's wishes himself. My dog has taught me many tricks which I gladly

carry out for him if he will only shake his tail vigorously enough.

When our beloved Steiner stayed for days under the cover of ginger plants in our yard, not eating,

not wagging his tail, and causing us concern, we followed Axel's wise advice and left him alone. We

only checked briefly each morning to see if he had survived the night, and were overjoyed when after

a week, his tail was wagging again and his normal habits returned with his sleeping in his bed in the utility

room at night. It's been several years since that trial on our patience and Steiner is alive and well as

ever.

[page 63, 64] Never disturb a sick dog when not absolutely necessary. As often

as not your untimely interference only distracts nature in her effort to assist

him to get well. All animals wish to be left alone when they are ill and also when

they are about to die.

Among the famous people Axel knew and worked with was Louis Pasteur during the time of his

experiments with a cure for hydrophobia. Axel assisted in the care of the six Russian peasants who had

been mauled by a pack of rabid wolves and were in Paris, seeking against all odds a cure from the

famous Pasteur.

Axel tackled an epidemic of diphtheria in a poor section of Paris with "no means of disinfection

either for others" or himself. Here's his report on that experience.

[page 83] I had to sit there for hours, painting and scraping the throat of one

child after another, there was not much more to be done in those days. And

then when it was no longer possible to detach the poisonous membranes

obstructing the air passages, when the child had become livid and on the point

of suffocation and the urgent indication for tracheotomy presented itself, with

lightning rapidity! Must I operate at once, with not even a table to put the child

on, on this low bed or on its mother's lap, by the light of this wretched oil-lamp

and no other assistant than a street-sweeper!

When the epidemic was over and he was able to return to his fashionable patients, he wondered

about leaving Paris entirely, but these thoughts came to him, about his rich, self-indulgent clientele which

now filled his days.

[page 85] What a waste of time! thought I as I walked home, dragging my tired

legs along, the burning asphalt of the Boulevards under the dust-covered

chestnut-trees gasping with drooping leaves for a breath of fresh air.

I know what is the matter with you and me," said I to the chestnut-trees, "we need a change of air, to get out of the atmosphere of the big city."

But how are we to get away from this inferno, you with your aching roots

imprisoned under the asphalt and with that iron ring round your feet, and I with

all these rich Americans in my waiting-room and lots of other patients in their

beds? And if I were to go away, who would look after the monkeys in the Jardin

des Plantes? Who would cheer up the panting Polar Bear, now that his worst

time was about to come? He won't understand a single word other kind people

may say to him, he who only understands Swedish! And what about Quartier

Montparnasse? Montparnasse! I shuddered as the word flew through my

brain, I saw the livid face of a child in the dim light of a little oil lamp, I saw the

blood oozing from the cut I had just made in the child's throat, and I heard the

cry of terror from the heart of the mother.

Were there spirit folk, goblins and such? Lars Anders told Axel a story which indicated that one

shouldn't be too sure that they don't exist. One man did and died.

[page 142, 143] Were there any Goblins in this neighborhood? Yes, there

were plenty of Little People sneaking about in the dusk. There was one little

goblin living in the cow-stable, the grandchildren had often seen him. He was

quite harmless as long as he was left in peace and had his bowl of porridge put

out for him in its usual corner. It would not do to scoff at him. Once a railway

engineer who was to build the bridge over the river had spent the night in the

Forsstugan. He got drunk and spat in the bowl of porridge and said he would

be damned if there was any such thing as a goblin. When he drove back in the

evening across the frozen lake his horse slipped and fell on the ice and was

torn to pieces by a pack of wolves. He was found in the morning by some

people returning from church, sitting in the sledge, frozen to death. He had shot

two of the wolves with his gun and had it not been for the gun they would have

eaten him as well.

There was a passage on page iv of the New Preface which needs to be quoted here.

[page iv] One reviewer has discovered that "there is enough material in 'The

Story of San Michele' to furnish writers of short sensational stories with plots

for the rest of their lives." They are quite welcome to this material for what it

is worth. I have no further use for it.

I would say there is material enough for a dozen or more different movies or just one epic movie

like "Doctor Zhivago" in this book, except for the absence of a prominent love story. My nomination

for the best story is the one in Chapter X The Corpse Conductor. No synopsis or review of the story

can do more than spoil the plot and surprise ending of this amazing story which Axel relates about

conducting an eighteen-year-old Swedish man home from San Remo. Dying of consumption, his mother

was called from Sweden to accompany the doctor and her son. When they arrived in Basel,

Switzerland, the mother had a heart attack which nearly killed her and necessitated that Axel put himself

and the dying son up in a fancy hotel, and wait for the mother's recovery. The son dies and suddenly Axel is faced with a dead person who needs to be embalmed and a hotel room being torn apart to remove the bed linens and carpets, all at Axel’s expense. He does a quick embalming based on his assisting at one while in medical school because it is much cheaper and he is footing the bill for the embalming. Then he tries to get the body onto the train and the train master insists that a Leichenbegleiter (Corpse companion) is necessary to accompany the body, someone who will ride in a sealed compartment with the coffin all the way to the ferry to Sweden. Axel won’t have that as he has seen more of the body than he wants and has already purchased himself a ticket in Second Class. What happens next is the meat of comedy, tragedy, farce, and human folly all rolled into one.

Just as the train car is about to be shuttled to the side track because of a lack of a companion, one

appears from nowhere, a dwarf who is a professional Leichenbegleiter. Axel is relieved but soon finds

out that this dwarf is here to be companion to a Russian general who had died and is being sent to

the same port to board a ferry to Russia. After some amazing maneuvering, Axel gets the station master

to sunder the bureaucratic morass of regulations and allow the dwarf to companion two corpses.

If you have guessed how this tale might end up, it is probably because someone has already taken

Axel's suggestion and written a story based on the plot of this true story as he experienced it. Will the

boy's mother survive and want to see her son's body? Will she be shocked when Axel opens the coffin

for her? Will his makeshift, home-brewed embalming preserve the boy's body? Truth is often stranger

than fiction, and this story proves the old adage. Here's a short piece of the amazing story, in which the

dachshund puppy which Axel bought as his own companion on the lugubrious journey, Waldmann,

plays an important part.

[page 198, 199] While the station master returned to the perusal of his

entangled documents, I took the hunchback aside, patted him cordially on the

back and offered him fifty marks cash and another fifty marks I meant to

borrow from the Swedish Consul in Lubeck if he would undertake to be the

Leichenbegleiter of the coffin of the boy as well as of that of the Russian

general. He accepted my offer at once. The station master said it was an

unprecedented case, it raised a delicate point of law, he felt sure it was

"verboten" for two corpses to travel with one Leichenbegleiter between them.

He must consult the Kaiserliche Oberliche Eisenbahn Amt Direktion Bureau,

it would take at least a week to get an answer. It was Waldmann who saved the

situation. Several times during our discussions I had noticed a friendly glance

from the station master's gold-rimmed spectacles in the direction of the puppy

and several times he had stretched his enormous hand for a gentle stroke on

Waldmann's long, silky ears. I decided on a last desperate attempt to move his

heart. Without saying a word I deposited Waldmann on his lap. As the puppy

licked him all over the face and started pulling at his porcupine moustaches, his

harsh features softened gradually into a broad, honest smile at our

helplessness. Five minutes later the hunchback had signed a dozen documents

as the Leichenbegleiter of the two coffins, and I with Waldmann and my

Gladstone bag was flung into a crowded second-class compartment as the train

was starting.

Of course, Waldmann was house-broken, but he was not permitted in second-class, and soon

both Axel and his traveling companion were relegated to the same space as the corpse companion and

the two corpses, and the five of them traveled to the port together, keeping each other company as

much as possible in the stuffy railroad car, during which much is revealed to Axel about the Russian

general and his embalming. Axel even got a much-needed shave from the dwarf, who had shaved many

corpses before and "never heard a word of complaint." Axel complained about being made to lie flat

on his back to be shaved, and got this explanation. "It is a matter of habit," explained the

Leichenbegleiter, "you cannot make a corpse sit up, you are the first living man I have ever shaved."

(Page 203)

Axel was forced into a duel by Vicomte Maurice after Axel saved a dog from being further

brutalized by the Vicomte. Axel couldn't shoot, had never shot a gun, and didn't plan to pull the trigger

at all, hoping the Vicomte would miss as often happened in those days. His gun went off much to his

surprise and mortally wounded the Vicomte. Axel was later surprised to find that a bullet had gone

through his own hat, barely missing his head, luck ever on Axel's side. When Rosalie come to see him with

his breakfast, he indicated he was going out in a half hour and this conversation ensued:

[page 246, 247] "But really Monsieur cannot go about visiting his patients in

this old hat, look! there is a round hole in front and here is another behind, how

funny! It cannot be made by a moth, the whole house is stinking with

naphthaline ever since Mamsell Agata came. Can it be a rat? Mamsell Agata's

room is full of rats, Mamsell Agata likes rats."

"No, Rosalie, it is the death-watch beetle, it has got

teeth as hard as steel and can make just such a hole in a man's

skull as well as in his hat, if luck is not on his side."

"Why does not Monsieur give the hat to old Don

Gaetano, the organ grinder, it is his day for coming and playing

under the balcony to-day."

"You are welcome to give him any hat you like but not

this one, I mean to keep it, it does me good to look at those two

holes, it means luck."

Dr. Axel Munthe always kept hope and small wooden horses in his medicine bag. Hope was what

he gave those patients with wretched doctors who had taken all hope away from them, making it likely

that they will die shortly of the fear imbued in them by their own well-meaning doctors. The wooden

horses were toys to give to children which had never had a toy or a small thing of their own to play with.

It was a child's token of hope and love. In one case he brought a still born baby boy to life using his

own breath and gave him up for adoption. Three years later he rescued the boy from an abysmal life

in a shoemaker's shop, looking like a skeleton, unkempt, barely alive. He became Axel's mascot for

Axel says he never slept so well as after he took a look at the little boy asleep in his cot before going

to bed. Later Rosalie, his housekeeper, and an elegant lady who never had a child of her own became

little John's daily caregivers. John loved riding in the lady's carriage, and she soon took to carrying him

upstairs and bathing him and seeing him to bed each day. After John died quite young, Axel embalmed

the body and gave him to the lady to bury in the parish churchyard near her home in Kent, England.

This time Axel didn't bother to ask permission, suggesting she place the body in its sealed coffin on her

yacht and sail away immediately. Hope and toys kept little John alive for years longer than his lugubrious

existence with the shoemaker would have.

Hope kept the elegant lady alive. Here is a bit of her story.

[page 258, 261] I had been chucked by the wife of the English parson, but

plenty of her compatriots were taking her place on the sofa in my waiting-room.

Such was the luster that surrounded the name of Professor Charcot that some

of its light reflected itself even upon the smallest satellites around him. English

people seemed to believe that their own doctors knew less about nervous

diseases than their French colleagues. They may have been right or wrong in

this, but it was good luck for me in any case. I was even called to London for

a consultation just then. No wonder I was pleased and determined to do my

best. I did not know the patient but I had been exceptionally lucky with another

member of her family which, no doubt, was the cause of my being summoned

to her. It was a bad case, a desperate case according to my two English

colleagues, who stood by the bedside watching me with gloomy faces while I

examined their patient. Their pessimism had infected the whole house, the

patient's will to recover was paralyzed by despondency and fear of death. It is

very probable that my two colleagues knew their pathology far better than I.

But I knew something they evidently did not know: that there is no drug as

powerful as hope, that the slightest sign of pessimism in the face or words of

a doctor can cost his patient his life. Without entering into medical details it is

enough to say that as a result of my examination I was convinced that her

gravest symptoms derived from nervous disorders and mental apathy. My two

colleagues watched me with a shrug of their broad shoulders while I laid my

hand on her forehead and said in a calm voice that she needed no morphia for

the night. She would sleep well anyhow, she would feel much better in the

morning, she would be out of danger before I left London the following day. A

few minutes later she was fast asleep, during the night the temperature

dropped almost too rapidly to my taste, the pulse steadied itself, in the morning

she smiled at me and said she felt much better.

Her mother implored me to remain a day longer in London, to see her

sister-in-law, they were all very worried about her. The colonel, her husband;

wanted her to consult a nerve specialist, she herself had tried in vain to make

her see Doctor Phillips, she felt sure she would be all right if she only had a

child. Unfortunately she had an inexplicable dislike of doctors, and would

certainly refuse to consult me, but it might be arranged that I should sit next

her at dinner so as at least to form an opinion of her case. May be Charcot

could do something for her?

Perhaps you have guessed that what Munthe did for her was to allow her to befriend the young

boy, John, take him on carriage rides, give him toys, and fill the void in her own life, truly a masterful

cure administered by a student of Charcot's. A Dickens story lived out and related by Axel Munthe.

There are many great stories in this book, but my favorite is the staging of Hamlet in Lund, Sweden

by a friend of Axel's, his old pal from the university in Upsala, Erik Carolus Malmborg, whose presence

prompted him to attend the production. Axel thought Erik was destined to become a priest back then,

but here he was appearing in the production of Shakespeare's Hamlet in the very town in Sweden that

Axel was visiting at the time. The production was, however, like many of Axel's patients when he was

called to them, on its death bed. The last series of performances had been disastrous and had left Erik and

his traveling theater company broke. Well, here's the rest of the story.

[page 273, 275] Suddenly I also remembered having heard that he had taken

to the stage, of course it must be my ill starred old friend who was the Hamlet

of to-night! I sent my card to his room, he came like a shot overjoyed to see me

after a lapse of so many years. My friend told me a distressing story. After a

disastrous series of performances to empty houses in Malmö the company,

decimated to one third of its members, had reached Lund the evening before

for a last desperate battle against fate. Most of their costumes and portable

belongings, the jewels of the queen mother, the crown of the king, Hamlet's

own sword which he was to run through Polonius, even Yorick's skull had been

seized by the creditors in Malmö. The king had got a sharp attack of sciatica

and could neither walk nor sit on his throne, Ophelia had a fearful cold, the

Ghost had got drunk at the farewell supper in Malmö and missed the train. He

himself was in magnificent form, Hamlet was his finest creation — it might have

been expressly written for him. But how could he alone carry the immense

burden of the five-act tragedy on his shoulders! All the tickets for the

performance tonight were sold out, if they should have to return the money,

complete collapse was inevitable. Perhaps I could lend him two hundred kronor

for old friendship's sake?

I rose to the occasion. I summoned a meeting of the leading stars of the

company, instilled new blood into their dejected hearts with several bottles of

Swedish punch, curtailed ruthlessly the whole scene with the actors, the scene

with the grave-diggers, the killing of Polonius,. and announced that, ghost or no

ghost, the performance was to take place.

It was a memorable evening in the theatrical annals of Lund. Punctually

at eight the curtain rose over the royal palace of Elsinore, as the crow flies not

an hour's distance from where we were. The crowded house chiefly composed

of boisterous undergraduates from the University proved less emotional than

we had expected. The entrance of the Prince of Denmark passed off almost

unnoticed, even his famous "To be or not to be" missed fire. The king limped

painfully across the stage and sank down with a loud groan on his throne.

Ophelia's cold had assumed terrific proportions. It was evident that Polonius

could not see straight. It was the Ghost that saved the situation. The Ghost was

I. As I advanced in ghost-like fashion on the moonlit ramparts of the castle of

Elsinore, carefully groping my way over the huge packing-cases which formed

its very backbone, the whole fabric suddenly collapsed and I was precipitated

up to the armpits in one of the packing-cases. What was a ghost expected to

do in similar circumstances? Should I duck my head and disappear altogether

in the packing-case or should I remain as I was, awaiting further events? It was

a nice question to settle! A third alternative was suggested to me by Hamlet

himself in a hoarse whisper: why the devil didn't I climb out of the infernal box?

This was, however, beyond my power, my legs being entangled in coils of rope

and all sorts of paraphernalia of stage craft. Rightly or wrongly I decided to

remain where I was, ready for all emergency. My unexpected disappearance

in the packing-case had been very sympathetically received by the audience,

but it was nothing compared to the success when, with only my head popping

out from the packing-case, I began again in a lugubrious voice my interrupted

recital to Hamlet. The applause became so frenetic that I had to acknowledge

them with a friendly wave of my hand, I could not bow in the delicate position

I was. This made them completely wild with delight, the applause never ceased

till the end. When the curtain fell over the last act I appeared with the leading

stars of the company to bow to the audience. They kept on shouting: "The

Ghost! The Ghost!" so persistently that I had to come forth alone several

times to receive their congratulations, with my hand on my heart.

We were all delighted. My friend Malmborg said he had never had a

more successful evening. We had a most animated midnight supper. Ophelia

was charming to me and Hamlet raised his glass to my health offering me in the

name of all his comrades the leadership of the company. I said I would have to

think it over. They all accompanied me to the station. Forty-eight hours later

I was back to my work in Paris not in the least tired. Youth! Youth!

Axel never knew what his income was as a doctor. He saw his profession like that of a priest, after

all, he asked of us Readers, "What was to the heart of the mother the value in cash of the life of her

child you had saved? What was the proper fee for taking the fear of death out of a pair of terror-stricken eyes by a comforting word or a mere stroke of your hand?" And his biggest question of all,

"Why didn't we build more hospitals and fewer churches, you could pray to God everywhere but you

could not operate in a gutter!" (Page 279) Axel knew about operating in a gutter, for often during the

cholera epidemic in Naples, that was where he found his patients dying as well as in the poorest

sections of Paris during the diphtheria epidemic.

"How much should one pay a doctor who saved both of one's legs from amputation?" I'm asking

the question for Axel, as he never asked it. But surely he must wondered that about Professor Tillaux,

the famous surgeon whose clinic was in Hôtel Dieu, who saved his own legs during a catastrophic

avalanche after his climb to the top of Mount Blanc, upon which he smoked his pipe in a place most

people are panting to catch some oxygen in the thin air. He had his boots cut from his feet after being

rescued and staggered into Tillaux's clinic.

[page 293] Professor Tillaux stood washing his hands between two operations

as I staggered into the amphitheater of Hôtel Dieu the next morning. As they

unwrapped the cotton wool round my legs he stared at my feet, and so did I,

they were black as those of a negro.

"Sacré Suédois, where the devil do you come from?" thundered the

Professor.

Tillaux had taught Axel enough surgery that he was sure Tillaux was going to amputate both his

legs. Any doctor in Paris would have done so, as Axel well knew. But Tillaux kept coming for six days,

three times a day until Axel was in the clear and then administered the worst penalty Axel could endure:

bed rest for six weeks. After that Axel walked on crutches for another month and he was all right. How

can one ever repay for such a doctoring?

The next time Axel needed doctoring was for his insomnia. His good friend Norstrom was his

doctor and his eventual cure was to insist that Axel Munthe return to his beloved San Michele, build

his own home there and never leave there so long his sight remained fully. Axel writes in the last

sentence before this next passage, "Voltaire was right when he placed sleep on the same level as hope."

This is a brilliant insight into what happens to the human being during sleep: hope is build up by our

spiritual guardians like corn ensiloed during the summer months to provide nourishment to animals

during the winter months when they survive on the ensiloed corn. When we awake we feed off of the

hope which our guardian angel and their helpers have ensiloed in our soul. Note especially near the end

of the passage where Axel's insomnia gives him a reputation for kindness.

[page 328, 329] I did not go off my head, I did not kill myself. I staggered on

with my work as best I could, careless, indifferent what happened to myself,

and what happened to my patients. Beware of a doctor who suffers from

insomnia! My patients began to complain that I was rough and impatient with

them, many of them left me, many stuck to me still and so much the worse for

them. Only when they were about to die did I seem to wake up from my torpor,

for I continued to take keen interest in Death long after I had lost all interest

in Life. I could still watch the approach of my grim colleague with the same

keenness I used to watch him with when I was a student at the Salle St. Claire,

hoping against hope to wrench his terrible secret from him. I could still sit the

whole night by the bedside of a dying patient after having neglected him when

I might have been able to save him. They used to say I was very kind to sit up

like that the whole night when the other doctors went away. But what did it

matter to me whether I sat on a chair by the bedside of somebody else or lay

awake in my own bed? Luckily for me my increasing diffidence of drugs and

narcotics saved me from total destruction, hardly ever did I myself take any

of the numerous sleeping-draughts I had to write out the whole day for others.

Rosalie was my medical adviser. I swallowed obediently tisanes after tisanes

concocted by her [RJM: herbal teas], French fashion, from her inexhaustible

pharmacopæia of miraculous herbs. Rosalie was very worried about me. I even

found out that often on her own initiative she used to send away my patients

when she thought I looked too tired. I tried to get angry but I had no strength

left to scold her.

Norstrom was also very worried about me. Our mutual position had now

changed, he was ascending the slippery ladder of success, I was descending.

It made him kinder than ever, I constantly marveled at his patience with me.

He often used to come to share my solitary dinner in Avenue de Villiers. I

never dined out, never asked anybody to dinner, never went out in society

where I used to go a lot before. I now thought it a waste of time, all I longed for

was to be left alone and to sleep.

Norstrom wanted me to go to Capri for a couple of months, for a

thorough rest, he felt sure I would return to my work all right again. I said I

would never return to Paris if I went there now, I hated this artificial life of a

big city more and more.

And so Axel returned to Capri, to Anacapri, to Mastro Nicola, to Timberius's summer palace's

ruins, to the San Michele Chapel where he spent the rest of his life, except for a winter or so in Rome

where he made money off rich Swedes and English folk to finance his work on his new home. "It was

all done by eye", Mastro Nicola called Axel's architectural design for San Michele.

[page 339] The huge arcades of the big loggias [RJM: vine-covered walkways]

rose rapidly out of the earth, one by one the hundred white columns of the

pergola [RJM: columned portico across front of home] stood out against the

sky. What had once been Mastro Vincenzo's house and his carpenter

workshop was gradually transformed and enlarged into what was to become my

future home. How it was done I have never been able to understand nor has

anybody else who knows the history of the San Michele of today. I knew

absolutely nothing about architecture nor did any of my fellow workers, nobody

who could read or writer ever had anything to do with the work, no architect

was ever consulted, no proper drawing or plan was ever made, no exact

measurements were ever taken. It was all done all'occhio as Mastro Nicola

called it.

[page 432] I told Mastro Nicola that the proper way to build one's house was

to knock everything down never mind how many times and begin again until

your eye told you that everything was right. The eye knew much more about

architecture than did the books. The eye was infallible, as long as you relied on

your own eye and not on the eye of other people.

At times Axel saw the red-cloaked figure walking among the loggia, the same one that had

appeared to him in a dream to tell him that he would build San Michele, and he seemed to be inspecting

the work of Axel and his workers. Surely this was Sant' Antonio, the patron saint of Anacapri, Axel

thought.

The episode in Chapter XXI about the telegram is worth the price of the book itself, but I will

leave it as a homework exercise, dear Reader, as it spans several pages — I will only hint at the delight

of the first telegram ever sent by wireless from the mainland to Capri using semaphores or flags. And

the anguish of the aged letter carrier Maria Porta-Lettere trying to deliver a telegram no one could

translate to God only knows who. Eventually, the Swedish minister arrived and wanted to know if Axel

got his telegram. Did he get it? Everyone in Anacapri got to see it, but not a single one could decipher

it! The minister insisted on knowing why he did not acknowledge his telegram and warn him about the

777 Phoenician steps he would have to climb to visit him!

[page 345] Of course I got it, we all got it, I nearly got drunk over it. He

softened a bit when I handed him the telegram, he said he wanted to take it to

Rome to show it to the Ministero delle Post e Telegrafi. I snatched it from him,

warning him that any attempt to improve the telegraphic communications

between Capri and the mainland would be strenuously opposed by me.

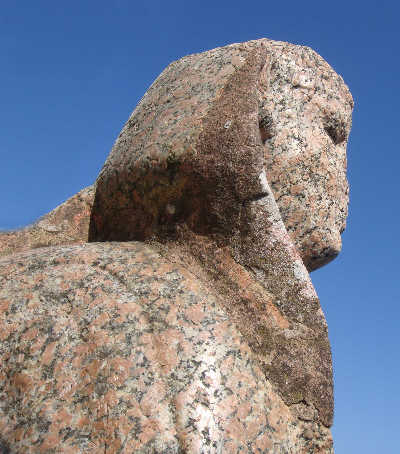

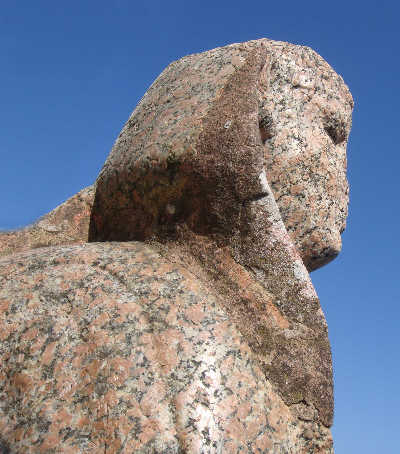

When Axel showed him around San Michele, the Minister was full of admiration, but when Axel

pointed out the place he had selected to install the huge Egyptian sphinx of red granite, the Minister

asked for a glass of wine and a quiet place to have a talk with Axel. Soon he was asking Axel about

who his architect was and about the source of his funding. A similar thing was asked me by my friend

Clay Andrews, also a doctor, when I told him that Axel tended the sick of Capri at no charge while he

built his beloved San Michele.

[page 347] He gave me another uneasy side glance and said he was at least

glad to know I had left Paris a rich man, surely it needed a huge fortune to

build such a magnificent villa I had described to him.

I opened the drawer of my deal table and showed him a bundle of

banknotes tucked in a stocking. I said it was all I possessed in this world after

twelve years' hard work in Paris, I believe it amounted to something like

fifteen thousand francs, maybe a little more maybe a little less, probably a little

less."

The Minister's advice to start up a practice in Rome during the winter months and spend his

summers in Capri shook Axel up so much that he took a swim in the sea and didn't dare to return to

San Michele until he had done so. And thus began his fortuitous adventures in the Piazza di Spagna area

of Rome, no doubt the very popular area now called the Spanish Steps. His first client had been treated

by all the doctors in Rome to no effect when Charcot himself recommended Axel to her, and soon

Axel's reputation was good as gold after Axel's strong dosage of hope and a minor massage got her

paralysis completed abated, and half the fashionable Roman society had seen her walking along the

Villa Borghese using only a cane.

[page 353] Soon it became very difficult for any foreigner in Rome to die

without my having been called in to see him through. I became to the dying

foreigners what the Illustrissimo Professore Baccelli was to the dying Romans

— the last hope, alas, so seldom fulfilled. Another person who never failed to

turn up on these occasions was Signor Cornacchia, the undertaker to the

foreign colony and director of the Protestant Cemetery by Porta San Paolo. He

never seemed to have to be sent for, he always seemed to smell the dead at a

distance like the carrion-vulture.

Plus, Axel's penchant for not setting any specific fee, nor bothering to send out bills, soon infuriated

the medical guild in Rome who sent a deputation to him with the aim of correcting this failing of his, as

they saw it, by insisting he join their Mutual Protection Society. Especially egregious was Axel charging

only a hundred francs for an embalming instead of the guild's fee of five thousand francs. Here in part

is Axel's answer to the deputy:

[page 355] I answered I was sorry I could not see the advantage either for me

or for them of my becoming a member, that anyhow I was willing to discuss with

them the fixing of a maximum fee but not of a minimum fee. As to the injections

of sublimate they called embalmment, its cost did not exceed fifty francs.

Adding another fifty for the loss of time, the sum I had charged for embalming

the parson's wife was correct. I intended to earn from the living, not from the

dead. I was a doctor, not a hyæna.

He rose from his seat at the word hyæna with a request not to disturb

myself in case I ever wished to call him in consultation, he was not available.

I said it was a blow both to myself and to my patients, but that we would have

to try to do without him.

The deputy was soon to call Axel to see him after a stroke, at which time he told Alex the guild

had been busted and he couldn't trust any of his so-called friends to heal him. Alex soon had him back

on his feet and flourishing.

Another hilarious moment came when Axel healed a monkey belonging to a retired old English

chemist, reported to be a renown surgeon for the South during the Civil War. The old monkey was a

horrible sight, having been almost scalded to death from upsetting a boiling tea kettle. The monkey,

named Billy, was fond of whiskey, as was the old doctor, and led to the drunken bout involving the two

of them, Billy and the old doctor, one day which Axel happened upon. Billy was later to come into

Axel's possession after the old doctor died and lived out his days with Axel in San Michele, sober of

course, Axel cured him of his dipsomania. Billy would do tricks for the chemist such as bringing him a

fig when asked, as he demonstrated to Axel. The old doctor called Billy his son, a term of endearment,

and understandable since Billy was the closest thing to a son the doctor had, often married, but having

no offspring, or did he? This sounds like something from the pen of a Southern writer like William

Faulkner.

[page 358, 359] Billy got slowly better. I saw him every day for a fortnight, and

I ended by becoming quite fond both of him and his master. Soon I found him

sitting in his specially constructed rocking chair on their sunny terrace by the

side of his master, a bottle of whisky on the table between them. The old doctor

was a great believer in whisky to steady one's hand before an operation. To

judge from the number of empty whisky bottles in the corner of the terrace his

surgical practice must have been considerable. Alas! they were both addicted

to drink, I had often caught Billy helping himself to a little whisky and soda out

of his master's glass. The doctor had told me whisky was the best possible

tonic for monkeys, it had saved the life of Billy's beloved mother after her

pneumonia. One evening I came upon them on their terrace, both blind drunk.

Billy was executing a sort of negro dance on the table round the whisky bottle,

the old doctor sat leaning back in his chair clapping his hands to mark the time,

singing in a hoarse voice:

"Billy, My son, Billy, my sonny, soooooooonny!" They neither heard

nor saw me coming. I stared in consternation at the happy family. The face of

the intoxicated monkey had become quite human, the face of the old drunkard

looked exactly like the face of a gigantic gorilla. The family likeness was

unmistakable.

"Billy, my son, Billy, my son, sooooooony!" Was it possible? No, of

course it was not possible but it made me feel quite creepy. . . .

Once Dr. Axel was called in by a dying man and was introduced to William James, the famous

psychologist, who was there to receive a message from his friend, his first words sent psychically from

the spiritual world after he died. Unfortunately James' pad was still empty when Axel left after the friend

died. (Page 373)

People might say that Axel was for the birds, and they would be right. He single-handedly got the

lucrative practice of netting and killing all the nesting migratory birds on the mountainside of Capri

outlawed. Do you know how they decoyed the birds into their nets to capture them? They used blind

birds. The blind bird sings all night.

[page 458] Long before science knew anything about the localization of the

various nerve-centers in the human brain, the devil had revealed to his disciple

man his ghastly discovery that by stinging out the eyes of a bird with a red-hot

needle the bird would sing automatically.

One had to sting the eyes out of the bird and have it survive, something that was very difficult to

do as only one out of a hundred birds survived the operation and lived to sing all night. Only when the

bird butcher of the Isle of Capri was dying, and asked, begged his sworn enemy Axel to attend to him,

did Axel extract a pledge from him to stop the butchery of the birds. Axel was truly for the birds.

In the amazing story of the Bambino (Jesus as a baby) we learn that a bush of rosemary in flower

is used every year to decorate the altar, actually the nursery of the Baby Jesus. Why rosemary?

"Because when the Madonna washed the linen of the Infant Jesus Christ, she hung his little shirt to dry

on a bush of rosemary." I read these words only a couple of weeks after seeing the first rosemary in

bloom while I was in California and have included a photo so you may see as well.

As the end of his life draws near, Axel Munthe leaves his beloved San Michele for the mainland

and the Tower of Materita where he will spend his time, dialoguing in earnest with his lifelong

companion, the earnest harvester who never gives up, never leaves a field unharvested, ungleaned,

removing the very last grain. The harvester asks if Axel wished a priest to be sent for, "They always

send for a priest when they see me coming." No, Axel replied, "It is no use sending for the priest, he

can do nothing for me now. It is too late for me to repent and too early for him to condemn, and I

suppose it matters little to you either way." Axel continues:

[page 511, 512] "I heard a golden oriole sing in the garden yesterday, and just

as the sun went down a little warbler came and sang to me under the window,

shall I ever hear him again?"

"Where there are angels there are birds."

"I wish a friendly voice could read the 'Phaedo' to me once more."

"The voice was mortal, the words are immortal, you will hear them

again."

"Shall I ever hear again the sounds of Mozart's Requiem, my beloved

Schubert and the titan chords of Beethoven?"

"It was only an echo from Heaven you overheard."

"I am ready. Strike friend!"

"I am not going to strike. I am going to put you to sleep."

"Shall I awake?"

No answer came to my question.

"Shall I dream?"

"Yes, it is all a dream."

Axel's book ends with a magnificent dream in which he is met by St. Peter who will not let him

enter until Axel tells him something he did that no other human had done. All the things that Axel thinks

of, St. Peter can think of many other men, many other doctors had done. Axel is saved at the last

second by a tiny bird, who landed on his shoulder and whispered into his ear, "You saved the life of

my grandmother, my aunt and my three brothers and sisters from torture and death by the hand of the

man on that rocky island. Welcome! Welcome!" St. Francis of Assisi rose in front of the mighty judges

and looked them in the eyes, "his wonderful eyes that neither God nor man nor beast could meet with

anger in theirs." At that, Axel's head sank on St. Francis's shoulder, thinking that he was dead and did

not know it.

A fitting end to the life of a fascinating man, Dr. Axel Munthe, architect and builder of San

Michele, and beloved doctor to the peoples of the Isle of Capri and the cities of Naples, Rome, and Paris.

~^~

---------------------------- Footnotes -----------------------------------------

Footnote 1.

The idea of a time wave from the future is embodied in my Matherne's Rule #36: Remember the future. It

hums in the present.

Return to text directly before Footnote 1.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~^~

Any questions about this review, Contact: Bobby Matherne

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

22+ Million Good Readers have Liked Us

22,454,155

as of November 7, 2019

Mo-to-Date Daily Ave 5,528

Readers

For Monthly DIGESTWORLD Email Reminder:

Subscribe! You'll Like Us, Too!

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

Click Left Photo for List of All ARJ2 Reviews Click Right Bookcover for Next Review in List

Did you Enjoy this Webpage?

Subscribe to the Good Mountain Press Digest: Click Here!

CLICK ON FLAGS TO OPEN OUR FIRST-AID KIT.

All the tools you need for a simple Speed Trace IN ONE PLACE. Do you feel like you're swimming against a strong current in your life? Are you fearful? Are you seeing red? Very angry? Anxious? Feel down or upset by everyday occurrences? Plagued by chronic discomforts like migraine headaches? Have seasickness on cruises? Have butterflies when you get up to speak? Learn to use this simple 21st Century memory technique. Remove these unwanted physical body states, and even more, without surgery, drugs, or psychotherapy, and best of all: without charge to you.

Simply CLICK AND OPEN the

FIRST-AID KIT.

Counselor? Visit the Counselor's Corner for Suggestions on Incorporating Doyletics in Your Work.

All material on this webpage Copyright 2019 by Bobby Matherne