In his swing through Europe giving lectures about education, Steiner was facing audiences

who were interested in education, but who were unfamiliar with the supersensible

consciousness upon which Waldorf education was based. He avoided the use of any

terminology that his audience was unfamiliar with, instead using common sense examples and

analogies from the material world. As René Querido says in his Introduction, these lectures

contain "a number of surprising jewels not found anywhere else" by learned readers of his

lectures, and they "could well be placed also in the hands of beginners who wish to find out

in a succinct and clear way what Waldorf Education was really about."

My undergraduate degree was in Physics, so I studied the basis of all the natural sciences

in my search to understand how the world worked. I did not want to be an engineer who builds

things, but rather to understand the nature of things. Nothing, however, that I learned in my

college days gave me any insight into the essence of life itself, what it means for me to be a

human being. I began to see life as a puzzle with an enigma on each end. What happened

before I was born, and what happens after I die. This formed an unanswered question in me

which led me to study the works of other writers and led me eventually to Rudolf Steiner who

provided answers to me in his spiritual science, anthroposophy, the science of the full human

being, body, soul, and spirit.

[page 2] Natural science, with its scrupulous, specialized disciplines,

provides exact, reliable information about much in our human

environment. But, when a human soul asks about its deepest, eternal

being, it receives no answer from natural science, least of all when science

searches in all honesty and without prejudice.

In earlier times, there was only one stream of knowledge which included two worlds: the

everyday world of the senses and the spiritual realities. Today most people accept only the

world of the senses, but back then one felt oneself as part of both worlds; in fact, the idea of

two worlds never occurred to anyone back then. Take, for example, humans in early stages of

Greece which was so different from ours today. Steiner explains with the analogy of a finger.

[page 6] During its earlier stages, the state of the human soul was not the

same as it is today, for in those days there still existed a dim awareness of

humanity's kinship with nature. Just as a finger, if endowed with some

form of self awareness, would feel itself to be a part of the whole human

organism and could not imagine itself leading a separate existence — for

then it would simply wither away — so the human being of those early

times felt closely united with nature and certainly not separate from it.

With the adoption of the Copernican Sun-centered view of the universe and the Baconian

method of focusing only on the external sensory world, the one stream of our earlier integrated

knowledge of the natural and spiritual worlds split into two separate streams of natural science

and spiritual science. Actually when the split occurred, and since then, the separate stream of

spiritual science was called metaphysics and disparaged by natural scientists as illusory and

superstitious. What Steiner has accomplished with his spiritual science is to demonstrate

conclusively that spiritual science can be as practical in enhancing our soul life as natural

science can be in enhancing our everyday physical life.

The curious thing that Steiner points out is how Aristarchus of Samos in ancient Greece

taught a Sun-centered view of our cosmos during a time when the Earth-centered view was

active. The Earth-centered view prevailed for some 2,000 years until Copernicus’s time. The Sun- or helio-centric

view was known in ancient mystery centers, but the leaders of these schools kept it secret from

the common person. Why?

[page 7, 8] Why were ordinary people left with the picture of the universe

as it appears to the eyes? Because the leaders of those schools believed that

before anyone could be introduced to the heliocentric system, they had to

cross an inner threshold into another world — a world entirely different

from the one in which people ordinarily live. People were protected from

that other world in their daily lives by the invisible Guardian of the

Threshold, who was a very real, if supersensible, being to the ancient

teachers.

Why was this a problem? Because if people could see into this world, it would be a world

lacking all soul and spirit!

[page 8, 9] But this is how we see the world today! We observe it and

create our picture of the realms of nature — the mineral, plant, and

animal kingdoms — only to find this picture soulless and spiritless. . . . it

is the kind of knowledge which has become a matter of general education

today.

When I took my first airplane ride at age twenty to travel 600 miles to a job interview, I

felt the loss of a firm ground under my feet! I felt like I was floating 30,000 feet in air above

the ground, as indeed I was. It took me several more flights before this curious sensation finally

left me. Now I read where Steiner described this as the type of feeling that the leaders of the mystery

schools encountered when teaching their students the heliocentric view of the Earth spinning

around the Sun. Their students would have fainted without proper preparation. In my early jet

airplane flights, I felt the world torn away from under me, exactly as the ancients would have

felt if taught the heliocentric view. What took long training of students in ancient times, I

overcame quickly because of the greatly increased human level of self-consciousness as it has

evolved in our time.

[page 9, 10] At the same time, we can see how we look at the world today

with a very different self-consciousness than people did in more ancient

times. The teachers of ancient wisdom were afraid that, unless their

pupils' self-consciousness had been strengthened by a severe training of

the will, they would suffer from overwhelming faintness of soul when they

were told, for example, that the earth was stationary but revolved around

the sun with great speed, and they too were circling around the sun. This

feeling of losing firm ground from under their feet was something that the

ancients would not have been able to bear. It would have reduced their

self-consciousness to the level of a swoon. We, on the other hand, learn to

stand up to it already in childhood.

It is because our consciousness has evolved to be primarily intellect-based that we can

handle, without extra training, concepts such as the heliocentric view of our Solar System

without feeling a loss of footing. We can see how, when we use intellectual reasoning we lose

all experience of our innate sense of feeling, i. e., as Steiner says on page 12, ". . . we are

deprived of the kind of knowledge for which our souls nevertheless yearn." It was indeed for

me the kind of knowledge I yearned for at age 22 and I had no idea where to seek this soul

knowledge, or even if there existed any such knowledge!

If we have intellectual honesty, we cannot imagine our natural world as split away from

the world of the spirit.

[page 23] We do not contemplate nature as being thus alienated from the

world of spirit. And, if people today are honest, they cannot help becoming

aware of the dichotomy between what is most precious in them on one

hand, and the interpretation of the world given by natural science on the

other.

One can look at the stark emptiness of a world devoid of soul portrayed in the dismal

ending scenes of the movie "A. I.". It is the world of people who have adopted the firm footing

of materialistic natural science and have developed a bleak view of the Earth as a tiny speck in

some desolate corner of the Universe which will eventually fall into the Sun and burn away

into nothingness. The very idea of nothingness is a nightmare for the natural scientist. They are

born out of nothing and die into nothing, just as their world itself will do. Life is hopeless and

everything we strive for will disappear in time. That is the message of natural science.

[page 24, 25] This is the point at which spiritual science enters, not just to

grant new hope and belief, but resting entirely on its own sure knowledge,

developed as I have already described. It states that the natural-scientific

theory of the world offers only an abstract point of view. In reality, the

world is imbued with spirit, and permeated by supersensible beings. If we

look back into primeval times, we find that the material substances of the

earth originated in the spiritual world, and also that the present material

nature of the earth will become spirit again in future times. Just as, at

death, the human being lays aside the physical body to enter, consciously,

a spiritual world, so will the material part of the earth fall away like a

corpse and what then is soul and spirit on earth and in human beings will

arise again in future times, even though the earth will have perished.

Christ's words — taken as a variation of this same theme — ring true:

"Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away."

Human beings thus can say, "Everything that our eyes can see will perish,

just as the body, the transient part of the human individuality does. But

there will rise again from this dying away what lived on earth as morality.

Human beings will perceive a spiritual world around them; they will live

themselves into a spiritual world."

Clearly our life is limited by the boundaries of birth and death, but everything we are doing

here on Earth of a moral nature will live on into another world we have no words to describe.

This realization is the goal of spiritual science.

[page 27] It enables us to become aware of our spirituality. It helps us see

in our fellows other beings of soul and spirit. And it helps us recognize that

our earthly deeds, however humble and practical, have a cosmic and

universal spiritual meaning.

"That all sounds good," you may be thinking, but what has spiritual science done to make

my world better?" The full answer to this question would require a detailed study of Rudolf

Steiner's works, but, in a few passages, he describes what has been done so far.

[page 28, 29] Last spring, I was able to show how what I could only sketch

tonight, as the beginning of spiritual-scientific research can be applied in

all branches of science. On that occasion, I showed doctors and medical

students how the results of spiritual science, gained by means of strict and

exact methods, can be applied to therapeutics. Medical questions, which

can often touch on other problems related to human health, are questions

that every conscientious doctor recognizes as belonging to the facts of our

present civilization.

[page 29, italics added] During that autumn course, specialists drawn from

many fields — law, mathematics, history, sociology, biology, physics,

chemistry, and pedagogy — tried to show how all branches of science can

be fructified by anthroposophical spiritual science. . . . The courses were

meant to show how spiritual science, far from fostering dilettantism or

nebulous mysticism, is capable of entering and fructifying all of the

sciences and that, in doing so, it is uplifting and linking each separate

branch to become part of a comprehensive spiritual-supersensible

conception of the human being.

In a few short pages Steiner has shown us that one can lead a practical life full of spirit by

grasping the real nature of spiritual science. Doing so is one of "the paramount needs of our

present age." (Page 30) He sums up his lecture this way:

[page 31] This gives us the hope that those who still oppose spiritual

science will eventually find their way into it because it strives toward

something belonging to all people. It strives toward the spirit, and

humanity needs the spirit.

Why do we need the spirit? Because almost one hundred years after Steiner gave these

lectures, we have learned a lot more about the physical body through advances in physiology,

psychology, and medicine. Yet we, in this nascent millennium, still have a lot to learn about

the greater part of the human being, the soul and spirit, and spiritual science can provide the

answers to the yearnings of our soul by continuing to expand our knowledge into soul and

spiritual realms.

[page 33] Only this spiritual-scientific continuation allows a person to

acquire the kind of knowledge that can answer the deepest longings in the

minds and the souls of modern human being. Thus, through spiritual

science, one really comes to know human beings.

In the list of fields (Page 29 above), I highlighted one special field that Steiner’s spiritual science can benefit, and that is pedagogy, the field of education. Steiner says on page 35, "One of the most important

practical activities is surely education of the young." A quick scan of the list of Waldorf

Education lectures that Steiner gave (see bottom of this review for the list or link to the list)

will show that all but a few of these lectures were given by him in the last five years of his life

(1919-1924). The Roots of Education (March, 1924) were the very last lectures on education

he gave, coming after over 6,000 other lectures during the previous 25 years. He gave few

lectures afterward and died in March, 1925. He had obviously come to realize that the best way

to apply his spiritual science to the practical needs of society was through bringing it into the

service of pedagogy. We need this especially for our children, who arrive in this world as

spiritual beings and deserve to be treated as such, not treated as fodder for some educational

machine to crush, manipulate, and spit out materialistic robots into society. No, our children

deserve the chance to meet their full potential as human beings, and Steiner-inspired Waldorf

educational principles groom teachers to recognize the soul-spiritual nature of each child

and assist each one to grow into a healthy, happy adult, living with an inner harmony of body,

soul, and spirit.

[page 36] And because spiritual science, in its own way, seeks the inner

harmony between knowledge, religious depth, and artistic creativity, it is

in a position to survey rightly — that is spiritually — the enigmatic,

admirable creation that is a human being and how it is placed in the

world.

In the above quote we can deduce that when Steiner says, "survey rightly," he means "understand spiritually." Similarly when he says, "understood rightly," as he does in many lectures, we can take him to mean, "understood spiritually."

If you have ever traced a great river from its source to its delta, you will have noticed that

at times, the water disappears beneath ground and appears again further downstream. It is the

same water appearing in a new location. Steiner uses this metaphor to describe how the way

one plays in one's early youth reappears in one's twenties as aptitude for finding one's way in

the world as an adult. I was fortunate to have four brothers and neighborhood kids to play with,

and our parents occasionally guided, but never restricted our play unless we caused harm to

ourselves or others, which was rare. We were never bored, always finding interesting things

to do, games to play, and fun ways to keep busy.

[page 39, 40] Now, careful observation will reveal that the way in which

people in their twenties adapt themselves to outer conditions of life, with

greater or lesser skill, is a direct consequence of their play activity during

early childhood.

Certain rivers, whose sources may be clearly traced, disappear

below the earth's surface during their course, only to resurface at a later

stage. We can compare this phenomenon with certain faculties in human

life. The faculty of playing, so prominent in a young child, is particularly

well developed during the first years of life. It then vanishes into the

deeper regions of the soul to resurface during the twenties, transmuted

into an aptitude for finding ones way in the world. Just think: by guiding

the play of young children, we, as educators, are directly intervening in the

happiness or unhappiness, the future destiny, of young people in their

twenties!

It is easy to agree with Steiner when he adds, "Such insights greatly sharpen our sense of

responsibility as educators."

This next passage illuminates the need for Waldorf teachers to follow their students from

the first to the eighth grades. It is the longitudinal experience with the growth of each pupil

which will inspire the teachers as they watch the external effects of the child's spirit

descending into and shaping its features, its bodily shape and its actions.

[page 40, 41] At this point, I should mention that those who choose to

become teachers or educators through anthroposophical spiritual science

are filled with the consciousness that a message from the spiritual world

is actually present in what they meet in such enigmatic and wondrous

ways in the developing human being, the child. Such teachers observe the

child with its initially indeterminate features, noticing how they gradually

assume more definite forms. They see how children's movements and life

stirrings are undefined to begin with and how directness and purpose then

increasingly enter their actions from the depths of their souls. Those who

have prepared themselves to become teachers and educators through

anthroposophical spiritual science are aware that something actually

descending from the spiritual worlds lives in the way the features of a

child's face change from day to day, week to week, and year to year,

gradually evolving into a distinct physiognomy. And they know too that

something spiritual is descending in what is working through the lively

movements of a child's hands and in what, quite magically, enters into a

child's way of speaking.

What is the inner mood of a teacher who wishes to take on the vocation of a Waldorf

teacher? Steiner describes this way:

[page 41] The spiritual worlds have entrusted a human soul into my care. I

have been called upon to assist in solving the riddles that this child poses. By

means of a deepened knowledge of the human being — transformed into a

real art, the art of education — it is my task to show this child the way into

life.

Now, ask yourself, dear Reader, is a person who undertook teaching in this manner

someone you would wish to educate your seven-year-old child? Riddles of childhood not

solved by a teacher are like unkissed bruises and bumps on a child's soul which will show up

later in various maladjustments to adult life. My surmise is that the increasing frequency of

adult children returning to their parent's home from some unsuccessful life experience

provides us ample examples of such maladjustments to adult life. Lacking a parental home to

return to, many choose homelessness rather than directly face the exigencies of adult life.

Unkissed bruises can harm the child when it grows into an adult, but not as much as can actually inflicting soul bruises by the premature teaching of reading before writing. Reading involves absorbing completely abstract figures, the letters of the alphabet, and teachers who require this be done by rote learning hit the child with a soul-deadening process, similar to the deadening that occurs from a shot of novocaine by the dentist. The difference is the dentist’s deadening goes away in a few hours, but the soul-deadening can remain unkissed bruises for the rest of a child’s life. Look into the childhood of an adult who reads only what is required by their job and cannot enjoy reading

for pleasure, and you will find someone who was forced at an early age to learn the abstract

letters of the alphabet.

The Waldorf system of teaching writing before reading sometimes creates children who

write and read later than traditionally-trained children. Steiner says that, instead of this being

a problem, the late start is often an advantage. (Page 47)

[page 47, 48] Of course, it is quite possible to teach young children reading

and writing by rote and get them to rattle off what is put before their eyes,

but it is also possible to deaden something in them by doing this, and

anything killed during childhood remains dead for the rest of one's life.

The opposite is equally true. What we allow to live and what we wake into

life is the very stuff that will blossom and give life vitality. To nurture this

process, surely, is the task of a real educator(1).

It is a curious paradox, one that will be lost on inveterate materialists, that much of what

they call the real world consists of completely abstract concepts. Every theory of theirs is filled

with abstract concepts, no matter how useful the theory in predicting events in the sensory

world. Their theories about human beings are also abstract and are applied to human beings

as if they were corpses, those inanimate material bodies lying on an autopsy table. Sometimes

their theories are useful. But theories applied, without the insights of spiritual science, are often incomplete and inaccurate. We need these expanded insights today more than ever to rescue us from a one-sided, materialistic view of the human being. No wonder that horror films about the walking-dead are so popular today. People sense unconsciously that they themselves are treated by

materialistic scientists as if they were mere dead matter which happens to be animated.

[page 49] The pressing demands of society show clearly enough the need

for such knowledge today. By complementing the outer, material aspects

of life with supersensible and spiritual insights, spiritual science or

anthroposophy leads us from a generally unreal, abstract concept of life

to a concrete practical reality. According to this view, human beings

occupy a cental position in the universe. Such realistic understanding of

human nature and human activities is what is needed today.

Where in all of pedagogy is it stated that what a teacher is thinking while speaking to a

class is more important than what the teacher is saying? There is one place, in the Final Paper

I wrote in 2003 for my graduate course "College Teaching." In the section called The Live

Lecturer in the Classroom I explain how I discovered that learning is received directly from the

teacher's mind and that what the teacher says is only the carrier wave of that learning. The real

learning proceeds from the soul of the teacher to the soul of the student on the wings of the words

spoken. [See the end of my review of Jerome Bruner's

The Process of Education where he describes how a college professor discovered this meaning-transfer process.]

Teachers can use the metaphor of the caterpillar becoming a butterfly to demonstrate this

soul to soul teaching and learning process. The first kind of teacher truly believes that this

story evokes the feeling and deep meaning of immortality of human beings, and that what flies

from the teacher's soul to the pupils' souls is this spiritual reality. The second kind of teacher

considers this butterfly life cycle to be a silly analogy, and as a result the pupils will receive only

the supercilious soul attitude of the teacher. Anyone monitoring the classrooms of the two

teachers will observe in the second kind's classroom, a complete lack of involved attention to

the teacher by the pupils, and in the first kind's classroom, a deep level of introspection by the

pupils. And while in the first kind of teacher’s classroom, such a powerful metaphor for immortality may

not be understood directly by the pupils, but it will embed an unanswered question in each of

their minds which will continue to bear fruit as they grow older. What kind of school has

teachers of the first kind?

[page 50] A Waldorf teacher, an anthroposophically oriented spiritual

researcher, would not feel, "I am the intelligent adult who makes up a

story for the children's benefit," but rather: "The eternal beings and

powers, acting as the spiritual in nature, have placed before my eyes a

picture of the immortal human soul, objectively, in the form of the

emerging butterfly. Believing in the truth of this picture with every fiber

of my being, and bringing it to my pupils through my own conviction, I

will awaken in them a truly religious concept. What matters is not so much

what I, as teacher, say to the child, but what I am and what my heartfelt

attitude is." These are the kinds of things that must be taken more and

more seriously in the art of education.

Here is another paradox: the meaning of the word maya has been completely reversed by

modern natural science. In ancient times, maya referred to the external sensory world which

to the ancients, offered them only the semblance or outer appearance of reality. Today, modern

science deems the external sensory world to be the only reality. This represents a complete

reversal of what counts as reality. Rightly understood, the word maya today must be

understood to mean ideology. And what is ideology but abstract logical concepts? This is the

reality in which we are doomed by materialists to live, move, and have our being. If we accept

the materialist's judgment, we live on a tiny mote in an insignificant galaxy in a remote part

of the universe, and upon tiny speck we call Earth all our dreams and accomplishments will

die a fiery death. (Page 53)

[page 54] According to natural science, what rises in the human soul as

ethics, religion, science or art, does not represent reality. Indeed, if we look

toward the end of earthly evolution as it is presented by science, all that is

offered is the prospect of an immense cemetery. On earth, death would

follow, due either to general glaciation, or to total annihilation by heat. In

either case, the result would be a great cemetery for all human ideals —

for everything considered to be the essence of human values and the most

important aspect of human existence. If we are honest in accepting what

natural science tells us — such people had to conclude — then all that

remains is only a final extinction of all forms of existence.

Steiner saw how such a view led to the materialism of the working class and he perceived

the catastrophes ensuing following the Russian revolution which lasted for seventy years and

planted its seeds of discord in other countries around the world. What is the alternate to such

a bleak world view?

[page 55] Anthroposophical spiritual science gives us not only ideas and

concepts of something real but also ideas and concepts by which we know

that we are not just thinking about something filled with spirit. Spiritual

science gives us the living spirit itself, not just spirit in the form of

thoughts. It shows human beings as beings filled with living spirit — just

like the ancient religions. Like the ancient religions, the message of

spiritual science is not just "you will know something," but "you will know

something, and divine wisdom will thereby live in you. As blood pulses in

you, so, by true knowing, will divine powers too pulse in you." Spiritual

science, as represented in Dornach, wishes to bring to humanity precisely

such knowledge and spiritual life.

Steiner observed the state taking over the schools from various denominations and thought

it was a good idea, but he knew that meant education would soon become a servant of the state.

He warned, "The state can train theologians, lawers, or other professionals to become its civil

servants, but if the spiritual life is to be granted full independence, all persons in a teaching

capacity must be responsible to the spiritual world, to which they can look up in the light of

spiritual science." He also predicted, "One must be clear that freedom from state interference in

education will be the call of the future." By doing so he foresaw the advent of "Charter

Schools" which provide a considerable degree of independence from the state schools today.

In New Orleans, the state and local bureaucracy ran horrible schools with a pitiful graduation

rate and abysmal level of educational achievement. No way out of this conundrum was deemed

possible until Hurricane Katrina blew through the city and cleared out the state schools which

were replaced by healthy and vibrant Charter schools. The snakes of coercion from the state

bureaucracy are trying to sneak back into control, and if they do, we can expect a repeat of the

former debacle.

On pages 58 and 59 Steiner discusses the economic sphere and uses the example of

"crabs" in the publishing business as one example of wasteful practices in his time. Back then,

what we know now as "remainders" in the book trade were called "crabs". Today with the

advent of Print-on-Demand books, books can be printed when an order is placed, and this

eliminates the wasteful and unprofitable "crabs" and keeps books available in print form

indefinitely.

What about health and illnesses in the school system? This is an area where Steiner's ideas

have been invaluable in the developing of the Waldorf School system. One of these is how the

introduction of writing, reading, and arithmetic assaults the child's nature. (Page 76) To

counter these necessary assaults, Waldorf teachers learn to first minimize them, by teaching

writing before reading using an artistic approach which harmonizes with the child's basic

artistic instincts. Secondly, the teachers attempt to restore a harmonic balance after these assaults. They ask themselves, “How do I heal the child from these necessary attacks required by civilization?” Awareness of this is required of the teachers.

[page 77] But this awareness is possible only if we have insight into the

whole human organization and really understand the conditions of that

organization. We can be proper teachers and educators only if we can

grasp the principle of the inflicting of malformations and their subsequent

harmonization. For we can then face a child with the assurance that,

whatever we are doing when teaching a subject and thereby attacking one

or other organic system, we can always find ways and means of balancing

the ill effects of leading the child into onesidedness.

This is one realistic principle and method in our education that

teachers can use and that will make them into people who know and

understand human nature. Teachers, if they are able to know the human

being as a whole, including the inherent tendencies toward health and

illness, can gradually develop this ability.

Steiner leaves us an unanswered question, "What is the opposite of illness?" We would

immediately think the answer is health, but he answers that it is "overabundant bliss". He says

that illness comes when one organ is out of whack. I think of it like the way one person out of

step in a marching band disrupts the harmony of the entire formation.

[page 78] What occurs in the case of illness is that a single organ, or

organic system, no longer operates within the overall general organization

but assumes a separate role. This has a complement in the case of a single

organization merging into the total organization.

One might imagine the role of a dictator like Hitler as an example of a single person merging

into a total organization. We call such a system a totalitarian system. Look at the bliss felt at

the huge Nazi rallies when Hitler spoke: can you understand this as bliss? And yet, the people

in rally felt it and it was clearly not healthy for the German people in the long run. Rightly

understood, health is a balance between illness and overweening bliss.

[page 79] Between these two extremes — of feeling ill or pained and the

feeling of well-being or organic bliss — a healthy human being must hold

the balance. This is what health really is: holding the balance.

Before teeth change around age 7, the child's forces are devoted to construction of the

physical body, and afterwards these same forces are diverted into the forces of idea-forming,

memory, and so on, the very forces teachers will call on for the child's educational development

in the primary grades. And teachers do best by activating these forces in an artistic fashion, such as

by teaching writing using artistic designs to develop the child's drawing of the otherwise

abstract letters of the alphabet. The other important aspect is to counteract these assaults on the

child during the morning sessions by devoting the afternoons to purely artistic bodily

movement sessions. In Waldorf schools, such a balance is maintained with watercolor and

eurythmy classes in the afternoons.

Steiner focuses particularly on the ages of 9, 10, and 11 leading up to puberty, saying how

important they are, because the soul spirit nature of the child is re-submerging into the physical

body as puberty approaches. As I recall, that age period was the time when I was taking out 5

books each week when I went to the Westwego Library and reading about every aspect of the

world I could find. I recall it had a collection of about 30 Dr. Doolittle books which I sailed

through because of the varied nature of the adventures the good doctor had. I learned

a lot about the world through his eyes.

[page 83, 84] Indeed our adolescents will develop abnormally if we do not

recognize that we must fill their souls and spirits that are submerging into

their physical being with an interest for the whole world. If we do not do

this, they will become inwardly excitable, nervous or neurasthenic (not to

speak of other abnormalities). As teachers, we must direct our pupils'

interests to the affairs of the wide world, so that our young people can take

into their bodily being as much as possible of what links them to the outer

world.

Waldorf education always comes down to practical application by teachers of their skills.

Rather than having a doctor stand alongside a teacher to determine what should be done for a

specific student, the teachers ingest a knowledge of the child's tendencies toward health or

illness.

[page 85, 86] A healthy situation is possible only when teachers let their

knowledge of health and illness permeate their entire teaching. Such a

thing, however, is possible only if a living science, as striven for by

anthroposophy, includes knowledge of healthy and sick human beings.

In those cases where the teacher must lead a child into onesided development in reading,

writing, and arithmetic, the teacher knows how to take measures to restore the child into

harmony again.

[page 86] If teachers are introduced to both healthy and sick development

of children in a living way, if they can harmonize those two aspects of child

development, then their own feeling life will at once be motivated. They

will face each individual child with his or her specific gifts as a whole

human being. Even if teachers teach writing in an artistic way, they can

still be guiding their children in a onesided way that comes very close to

malformation. But, at the same time, they also stand there as whole human

beings, who have a rapport with their children's whole beings and, in this

capacity, as whole human beings, they themselves can be the counterforce

to such onesidedness.

The teacher learns to develop and utilize the wordless communication from soul to soul.

That is the key to 1,001 imponderables when Steiner refers to in the next passage:

[page 86, italics added] There are two things that must always be present

in education. On one hand, the goal of each particular subject and, on the

other, the 1,001 imponderables which work intimately between one human

being and another.

Teachers do best when they allow their children to open their inner beings to them. When

children believe in the authority of the teacher, the teacher becomes the whole world for them.

This teacher-world continues until the children are released into the outside world upon

graduation. The reason for this change being called commencement is that the children begin

their participation in the larger world outside. (Page 121)

[page 121] If they find a world in us as their teachers, then they receive the

right preparation to become reverent, social people in the world. We

release them from our authority which gave them a world, into the wide

world itself.

People who cannot hold unanswered questions do best to avoid becoming teachers. One

can spot such people because they have an "I know that!" attitude about most any subject one

talks about or discusses with them. Such people, if they became teachers, would likely use familiar

clichés to talk to their children because the clichés describe what they understand.

Unfortunately, if their understanding is at the shallowest level, such teachers will quickly lose

the attention of their children in a classroom. Why? Because they have only the cliché to

describe their shallow understanding and that shallow understanding flows unabsorbed through

their children's ears and souls.

[page 132] And what happens when we speak in clichés — no matter

whether the subject is religious, scientific, or unconventionally open-minded? The child's soul does not receive the necessary sustenance, for

empty phrases cannot offer proper nourishment for the soul.

Children clearly will not love a teacher whose forté is the empty phrase or cliché. Steiner

understood that, and whenever he visited a Waldorf classroom, he asked one specific question

of the students there whose response gave him immediate confirmation that the Waldorf

teacher was doing a great job. Can you imagine what such a question might be?

[page 133] I must confess that whenever I come to Stuttgart to visit and

assist in the guidance of the Waldorf School — which unfortunately

happens only seldom — I ask the same question in each class, naturally

within the appropriate context and avoiding any possible tedium,

"Children, do you love your teachers?" You should hear and witness the

enthusiasm with which they call out in chorus, Yes!" This call to the

teachers to engender love within their pupils is all part of the question of

how the older generation should relate to the young.

I daresay few if any teachers could receive such an enthusiastic response in any classroom

of the average state-run school system today.

Steiner gave over 6,000 lectures in twenty-five years, and never spoke using empty phrases

or clichés. His words, even if talking about a subject he had lectured on before always came

straight from his heart. When we say someone speaks from the heart, we are describing the

process of knowledge flying from the speaker on the wings of words, from one heart to another

heart.

[page 137] It might surprise you to hear that in none of the various

anthroposophical conferences that we have held during the past few

months was there any lack of younger members. They were always there

and I never minced my words when speaking to them. But they soon

realized that I was not addressing them with clichés or empty phrases.

Even if they heard something very different from what they had expected,

they could feel that what I said came straight from the heart, as all words

of real value do.

The practice of foot-binding of young Chinese girls to maintain a small size for their

females, thought to make them prettier, has been universally decried and has disappeared from

use in modern China. But the same liberal thinkers who would decry foot-binding can often

be found teaching children using abstract concepts that are soul-binding, providing soul-shoes

too tight for the children's souls to expand into, producing children of small souls and

constricted understanding of the world. The result is not pretty.

[page 152] It is so easy to feel tempted to teach children clearly defined and

sharply contoured concepts representing strict and fixed definitions. If one

does so, it is as if one were putting a young child's arms or legs, which are

destined to continue their growth freely until a certain age, into rigid

fetters. Apart from looking after a child's other physical needs, we must

also ensure that its limbs grown naturally, unconstricted, especially while

it is still at the growing stage. Similarly, we mst plant into a child's soul

only concepts, ideas, feelings, and will impulses that, because they are not

fixed into sharp and final contours, are capable fo further development.

Rigid concepts would have the effect of fettering a child's soul life instead

of allowing it to evolve freely and flexibly. Only by avoiding rigidity can

we hope that what we plant into a child's heart will emerge during later

life in the right way.

When we understand as teachers, that what we plant in and instill into our children’s hearts will appear much later in life, it should be clear that what can be represented as a letter grade on a

report card at the end of one year is little more than a shallow cliché. This is why Waldorf

School teachers prepare a poem at the end of a term for each student, a poetic representation

which may contain numerous unanswered questions to fructify the child's entire adult life to

come.

Steiner could see no use for experiments done with children. One need only look at an

early experiment when Frederick the Great had a group of children isolated from birth to

discover what language they would speak naturally. The result of the experiment was that all

the children died from lack of human contact! In a similar but less serious vein, the

experiments done on modern day children are death-dealing and soul-weakening.

[page 153] What does one seek to discover through experiments in

children's powers of comprehension, receptivity to sense impressions,

memory, and even will? All of this shows only that, in our present

civilization, the direct and elementary relationship of one soul to another

has been weakened. For we resort today increasingly to external physical

experimentation rather than to a natural and immediate rapport with the

child, as was the case in earlier times. To counterbalance such

experimental studies, we must create new awareness and knowledge of the

child's soul. This must be the basis of a heathy pedagogy.

One will often see people walking and talking together. This is a natural and enjoyable

way to have a conversation between two people. The basis of this felt

enjoyment goes back to how we develop our will and feeling organizations in

our childhood.

[page 155] As young children are learning to walk, they are developing in

their brains — from below upward, from the lower limbs and in a certain

way from the periphery toward the center — their will organization.

In other words: when learning to walk, a child develops the will

organization of the brain through the will activity of its lower limbs.

Next comes the development of the breathing organization which forms the basis of our

ability to talk.

[page 155] The breathing assumes what I should like to call a more

individual constitution, just as the limb system did through th activity of

walking. And this transformation and strengthening of the breathing —

which one can observe physiologically — is expressed in the whole activity

of speaking.

Once more, as with walking, there is a development from below upward.

[page 155] We can follow quite clearly what a young person integrates into

the nervous system by means of language. We can see how, in learning to

speak, ever greater inwardness of feeling begins to radiate outward. As a

human being, learning to walk becomes integrated into the will sphere of

the nervous system, so, in learning to speak, the child's feeling life likewise

becomes integrated.

Thus as adults, our will and feeling functions are most in harmony with each other when

we walk and talk together with someone. There's an old popular song which goes: "Let's go

for an old-fashioned walk, I'm just bursting with talk; what a tale could be told if we went for

an old-fashioned walk." There is much truth in those lyrics. So often in a movie, we'll see a

man go to talk to his boss, and his boss says, "Walk with me." What could otherwise seem like

a move to save time, can now be seen as a way to facilitate the talking by creating a harmony

with the walking.

Another insight which Steiner shares is that vowels come from a mother's soul and

consonants from a father's movements. Certainly the first words spoken by a baby illustrate

this: mama and dada. Say these words and notice how ma-ma focuses on an inner vowel sound,

and da-da focuses on an outward striving consonant which one almost has to spit out to speak.

For over thirty years, since my first grandchild was born, I have insisted that they call me Granpa. Now, it occurs to me why I like the name: it combines a mother's vowel sound 'an' and a father's consonant sound, the 'pa', giving it an androgynous quality which fits best with my approach to being a grandparent.

[page 156] It is wonderful to see, for example, what happens when

someone — perhaps the mother or another — is with the child when it

learns to speak the vowels. A quality corresponding to the soul being of the

adult who is in the child's presence flows into the child's feeling through

these vowels. On the other hand, everything that stimulates the child to

perform its own movements in relation to the external world — such as

finding & the right relationship to warmth or coldness — leads to the

speaking of consonants. It is wonderful to see how one part of the human

organism, say moving of limbs or language, works back into another part.

In the nascent science of doyletics, we postulate that our early memories are full body

states which we call doyles, and our later memories involve more cognitive images and

thinking, a process which neuroscientists call declarative memories. In this next passage

Steiner, speaking a hundred years or so ago, said essentially the same thing. Natural science

has been able to pinpoint the hippocampus of the brain as the gateway which transmits the

experienced events to the cortex for later recall as thinking and images. Our limbic system in

the root brain stores the bodily states for later recall as bodily states or doyles whenever the

hippocampus is not functional; this includes the pre-teeth-change stage of growth and the

later-in-life times of external stress. An extreme stress event will flood the hippocampus with

glutocorticoids, rendering it temporarily non-functional, causing doyles to remain in the limbic

region and resulting in post-traumatic stress syndrome episodes as these stored bodily states (doyles) bleed through.

[page 156] . . . just as we see that a child's will life is inwardly established

through the ability to walk, and that a child's feeling life is inwardly

established by its learning to speak so, at the time of the change of teeth,

around the seventh year, we see the faculty of mental picturing or thinking

develop in a more or less individualized form that is no longer bound to

the entire bodily organization, as previously.

It is important for a teacher to connect with a child using an artistic approach, especially

during the earliest years of a child's life. He says on page 116 that, "A true teacher(2) of our time

must never lose sight of the whole complex of such interconnections."

Steiner refers to the "etheric body" as the "time organism" as he focuses on the post-teeth

change development of the child.

[page 166] There is one moment of special importance, approximately

halfway through the second life period; that is, roughly between the ninth

and tenth years. This is a point in a child's development that teachers need

to observe particularly carefully. If one has attained real insight into

human development and is able to observe the time organism or etheric

body, as I have described it, throughout the course of human life, one

knows how, in old age, when a person is inclined to look back over his or

her life down to early childhood days, among the many memory pictures

that emerge, there emerge particularly vividly the pictures of teachers and

other influential figures of the ninth and tenth years.

The age of 9 and 10 was a time of a lot of early reading for me. I went to our public library

once or twice a week, bringing home five books each time, the most allowed to be checked out.

The librarian, Mrs. Edith Lawson, was a very influential person in my life, and one vivid image

of her sticks in my mind. I was checking my selected books one day and she carefully inspected

this one book, looking at the book, and then into my eyes before finally allowing me to take

the book. She gave me no reason for this unusual delay, so it remained an unanswered question

until a decade or so later, when I realized the cartoon character, whose adventures in the human

body I wanted to see drawn out like a comic book for me, was a syphilis bug. Not even

understanding it was about a disease, I learned a lot about syphilis, how it enters through the

skin and how the disease can cause blindness, for example.

[page 156] What enters a child's unconscious then emerges again vividly

in old age, creating either happiness or pain, and generating either an

enlivening or a deadening effect. This is an exact observation. It is neither

fantasy nor mere theory. It is a realization that is of immense importance

for the teacher. At this age, a child has specific needs that, if heeded, help

bring about a definite relationship between the pupil and the teacher.

A teacher simply has to observe the child at this age to sense how

a more or less innate and unspoken question lives in the child's soul at this

time, a question that can never be put into actual words.

In this next passage Steiner makes explicit an insight I mentioned earlier about the need

for a live lecturer in a classroom. My insight was this: what was communicated soul-to-soul without

being spoken was as important or more important than what was spoken. Children may rebut

a teacher's words, but cannot rebut an insight received directly in their souls.

[page 168] People of materialistic outlook usually believe that whatever

affects children reaches them only through words or outer actions. Little

do they know that quite other forces are at work in children!

There was nothing in my college schooling or in the extensive literature I have read which

revealed this reality about children to me before I encountered it in Steiner's lectures. I was

taught to believe that the content of words spoken was the sole communication. Later when I

studied with Richard Bandler, he taught me that there was an invisible communication channel

in the tone one used when one spoke. Amazing, but still a materialistic aspect of

communication. What Steiner reveals here is a mode of communication that would have to be

ESP (extrasensory perception) by materialists, but it really exists and can be discovered and

utilized effectively by teachers and others.

[page 169] Unseen supersensible — or shall we say imponderable — forces

are at work here. It is not the words that we speak to children that matter,

but what we ourselves are — and above all what we are when we are

dealing with our children.

We must learn to think of our words as the mere carrier waves of the reality we transmit

(to use a radio metaphor). Or perhaps think of our words as carrier pigeons who carry tiny

capsules bound to their feet which contains the real message, the soul message we wish to send

to the other person. What we think about when we speak, speaks louder than the words we use,

rightly understood.

Words as Carrier Pigeons

Meanings fly from soul to soul

on the wings of words

Meanings are carried like cargo

on the wings of words

Meanings are soul messages

carried on the wings of words

Words are but the carrier pigeon

with an encapsulated soul message

Words are not the message

only its carrier pigeon

Bearing capsules of soul and spirit

between two people.

See my review of Towards Imagination, which contains my poem "On the Wings of

Words", for an earlier incarnation of this idea. These capsules of soul and spirit by a parent or

a teacher become implanted in the children and ripen into fruit later in their life.

[page 173] We can therefore plant something like soul-spiritual seeds in

our children that will bear fruits of inner happiness and security in

practical life situations for the rest of their earthly existence.

Some children encounter great difficulties as they grow into early adulthood, being unable

to cope with the challenges of life, flunking out of college, being unable to hold a job, etc.

Steiner explains how this might happen.

[page 180] If we are asked, "Why has a particular child not developed a

healthy ability to discriminate by the time they are thirteen or fourteen?

Why do they make such confused judgments?" We often have to answer,

"Because the child was not encouraged to make the right kinds of physical

hand and foot movement in early childhood."

Eurythmy in Waldorf schools teaches the child to make physical hand and foot movements

because it is speech made visible. Steiner says on page 181, "Each single movement — every

detail of movement that is performed eurythmically — manifest such laws of the human

organism as are found in speech or song." If the child doesn't receive the right kind of hand

and foot movements from its parents during pre-school time, it can receive it during Waldorf

school time.

I grew up as the son of a blend of German and Cajun parents. They were always using

their hands and I mimicked them. Mom crocheted and I even learned to do a little of it myself

as the oldest child. My dad while listening the Gillette Friday night boxing matches would knit

crab and shrimp nets using a hand-made tool and I learned to do a bit of that also. He bought

scraps of lead, heated the lead on the stove, and poured it into wooden forms to make the lead

weights for the edge of the shrimp cast nets he knitted. I got a lead soldier kit from Santa which

I made soldiers melting the lead as I saw my dad do it. If we needed something to use or work

with, Dad always made it by hand, often from discarded material. He built a trailer using the

rear axle on a junk auto. He built a crab boiling burner from a discarded water heater burner.

When he added on a room to our first home, he showed me how to toenail a vertical stud to

keep it upright.

Most of my early footwork was learning to quickly get out of his way when

he was working and to fetch something he needed quickly. My fine motor skills developed as

I watched my dad working in various ways, e. g., building himself a pirogue, resoling our

shoes, cutting my hair and my brothers's hair, catching fish, dancing, hunting, playing, etc. He

rarely told me what was the right thing to do, but he quickly corrected me if he sensed I was

doing something wrong. Stealing and hurting some else brought his wrath quickly. He was my

first teacher about what it was to be a man. From my mother I learned what it was to raise

small children, how to burp them, change their diapers, rock them to sleep, kiss their bruised

knees, and feed them, etc. By age 20 I could have written the Dr. Spock book on parenting.

[page 189] Listen carefully to what I say: teachers do not implant an

ethical attitude by moralizing. To the child, they are morality personified,

so that there is truly no need for them to moralize. Whatever they do will

be considered right; whatever they refrain from doing will be considered

wrong. Thus, in living contact between child and teacher, an entire system

of sympathies and antipathies regarding matters of life will develop.

Through those sympathies and antipathies, a right feeling for the dignity

of human beings and for a proper involvement in life will develop.

Later as the child reaches puberty, these sympathies and antipathies grow into a sense of

morality and moral principles, "a moral attitude of soul".

[page 191] This is the wonderful secret of puberty. It is the metamorphosis

of what had previously lived in the child as living morality into a conscious

sense of morality and of moral principles.

Once more Steiner gives us insight into how what a child learns in early life becomes a

source of youthful energy as one ages into the mid-thirties, the mid-fifties, and beyond. A true

teacher will recognize this and accept this responsibility as a sacred trust to ensure that the

child matures in a healthy fashion.

[page 192] Only at the age of about 35, does a person's soul begin to loosen

itself somewhat from the physical body. At that point, two ways are open

to us — although, unfortunately, all too often there remains no choice. At

that moment, when our souls and spirits free themselves from our physical

bodies, we can keep alive within us the living impulses of feeling, will, and

concepts that are capable of further growth and that were implanted in

our souls during childhood days. In that case, we not only remember

experiences undergone at school but can relive them time and again,

finding in them a source of ever-renewing life forces. Although, naturally,

we grow old in limbs, with wrinkled faces and grey hair and possibly even

suffering from gout, we will nevertheless retain a fresh and youthful soul

and, even in ripe old age, one can grow younger again without becoming

childish.

What some people, perhaps at the age of 50, experience as a second

wave of youthful forces is a consequence of the soul's having become

strong enough, through education, to enable it to function well not only

while it has the support of a strong physique but also when the time comes

for it to withdraw from the body.

Waldorf School teachers do not give a letter or number grade at the end of each term.

Steiner said that he was unable to distinguish from a B or B- or satisfactory versus

unsatisfactory grade. (Page 194) Instead of such grades, the Waldorf teachers write a summary

of the child's life during the year plus a short poem, a verse for the child to consider. I would

hope the verse would contain several unanswered questions for the child to ponder during the

next year and to have answers revealed during the child's later adult life.

[page 195] We do not make use of such marks in our reports. We simply

describe the life of the pupil during the year, so that each report represents

an individual effort by the teacher. We also include in each report a verse

for the year that has been specially chosen for the individuality of the child

in words with which she or he can live and in which he or she can find

inner strength until the coming of a new verse at the end of the next school

year. In that way, the report is an altogether individual event for the child.

Proceeding thus, it is quite possible for the teacher to write some strong

home truths into a report. The children will accept their mirror images,

even if they are not altogether pleasing ones. In the Waldorf school, we

have managed this not only through the relationship that has developed

between teachers and pupils but also, above all, through something else

that I could describe in further detail and that we can call the spirit of the

Waldorf school. This spirit is growing; it is an organic being. Naturally, I

am speaking pictorially, but even such pictures represent a reality.

My parents and my teachers deserve a "poem grade" for the good work they have done so that

I am healthy and happy, and am still working actively as I near 80. It is with gratitude and

thanks that I close this review with a verse for them.

True teachers all,

You inspired me:

Giving me many unanswered questions

to enrich my later life.

Modeling for me

how to use my hands and feet

in fun and productive deeds.

Teaching me to hold my hands

in prayer as a child

So that I may be able

to bless those in need now.

May God Bless all of you

for the abundance of Blessings

you have bestowed upon me.

~^~

---------------------------- Footnotes -----------------------------------------

Footnote 1.

In my review of Human Values in Education, I wrote 20 short stanzas most of which begin with "A true teacher

. ." inspired by Steiner's lectures in the book. This one is a propo of the above passage: "A true teacher allows a

child to learn by doing so they may grow into a full human being instead of a small professor." Read its Endnote

here: http://www.doyletics.com/arj/humanval.shtml#N_20_

Return to text directly before Footnote 1.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Footnote 2.

See my review of Human Values in Education which contains 20 stanzas of free verse which begin with "A

teacher" or "A true teacher".

Return to text directly before Footnote 2.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

RUDOLF STEINER'S LECTURES

and WRITINGS ON EDUCATION

LEGEND: (TBA) indicates this review to be added later.

Underlined Title indicates Available Review: Click on Link to Read Review.

(NA) indicates the Book is NOT in Print presently, so far as we know.

I. Allgemeine Menschenkunde als Grundlage der Pädagogik: Pädagogischer Grundkurs,

14 lectures, Stuttgart, 1919 (GA 293). Previously Study of Man.

The Foundations of Human Experience (Anthroposophic Press, 1996).

II. Erziehungskunst Methodische-Didaktisches, 14 lectures, Stuttgart, (GA 294). Practical Advice to Teachers (Anthroposophic Press, 2000).

III. Erziehungskunst, 15 discussions, Stuttgart, 1919 (GA 295). Discussions with Teachers (Anthroposophic Press, 1997).

IV. Die Erziehungsfrage als soziale Frage, 6 lectures, Dornach, 1919 (GA 296). Previously

Education as a Social Problem. Education as a Force for Social Change

(Anthroposophic Press, 1997).

V. Die Waldorf Schule und ihr Geist, 6 lectures, Stuttgart and Basel, 1919

(GA 297). The Spirit of the Waldorf School (Anthroposophic Press, 1995).

VI. Rudolf Steiner in der Waldorfschule, Vorträge und Ansprachen, 24 Lectures and conversations and one essay, Stuttgart, 1919-1924 (GA 298) Rudolf Steiner in the Waldorf School: Lectures and Conversations

(Anthroposophic Press, 1996).

VII. Geisteswissenschaftliche Sprachbetrachtungen, 6 lectures, Stuttgart, 1919

(GA 299). The Genius of Language (Anthroposophic Press, 1995).

VIII. Konferenzen mit den Lehrern der Freien Waldorfschule 1919-1924, 3 volumes

(GA 300a-c). Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner, 2 volumes: Volume 1, Volume 2 (Anthroposophic Press, 1998).

IX. Die Erneuerung der pädagogisch-didaktischen Kunst durch Geisteswissenschaft,

14

lectures, Basel, 1920 (GA 301). The Renewal of Education (Anthroposophic Press, 2001).

X. Menschenerkenntnis und Unterrichtsgestaltung, 8 lectures, Stuttgart, 1921

(GA 302). Previously The Supplementary Course: Upper School and Waldorf Education

for Adolescence. Education for Adolescents (Anthroposophic Press, 1996).

XI. Erziehung und Unterricht aus Menschenerkenntnis, 9 lectures, Stuttgart, 1920, 1922,

1923 (GA 302a). The first four lectures are in Balance in Teaching (Mercury Press, 1982); last

three lectures in Deeper Insights into Education (Anthroposophic Press, 1988).

XII. Die gesunde Entwicklung des Menschenwesens, 16 lectures, Dornach, 1921-22

(GA 303). Soul Economy: Body, Soul, and Spirit in Waldorf Education (Anthroposophic Press, 2003).

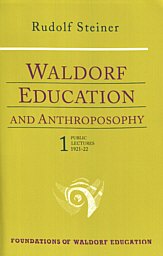

XIII. Erziehungs- und Unterrichtsmethoden auf anthroposophischer Grundlage, 9 public lectures, various cities, 1921-22 (GA 304)

Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy 1 (Anthroposophic Press, 1995).

XIV. Anthroposophische Menschenkunde und Pädagogik, 9 public lectures, various cities,

1923-24 (GA 304a). Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy 2 (Anthroposophic Press, 1996).

XV. Die geistigseelischen Grundkräfte der Erziehungskunst, 12 Lectures, 1 special lecture,

Oxford, 1922 (GA 305). The Spiritual Ground of Education (Anthroposophic Press, 2004).

XVI. Die pädagogische Praxis vom Gesichtspunkte geisteswissenschaftlicher

Menschenerkenntnis, 8 lectures, Dornach, 1923 (GA 306) The Child's Changing Consciousness as the Basis of Pedagogical Practice (Anthroposophic Press, 1996).

XVII. Gegenwärtiges Geistesleben und Erziehung, 14 lectures, Ilkley, 1923

(GA 307) Two Titles: A Modern Art of Education (Anthroposophic Press, 2004) and

Education and Modern Spiritual Life (Garber Publications, 1989).

XVIII. Die Methodik des Lehrens und die Lebensbedingungen des Erziehens, 5 lectures,

Stuttgart, 1924 (GA 308). The Essentials of Education (Anthroposophic Press, 1997).

XIX. Anthroposophische Pädagogik und ihre Voraussetzungen, 5 lectures,

Bern, 1924 (GA 309) The Roots of Education (Anthroposophic Press, 1997).

XX. Der pädagogische Wert der Menschenerkenntnis und der Kulturwert der Pädagogik, 10 public lectures, Arnheim, 1924 (GA 310) Human Values in Education(Rudolf Steiner Press, 1971).

XXI. Die Kunst des Erziehens aus dem Erfassen der Menschenwesenheit, 7 lectures, Torquay,

1924 (GA 311). The Kingdom of Childhood (Anthroposophic Press, 1995).

XXII. Geisteswissenschaftliche Impulse zur Entwicklung der Physik. Erster

naturwissenschaftliche Kurs: Licht, Farbe, Ton — Masse, Elektrizität, Magnetismus

10 lectures, Stuttgart, 1919-20 (GA 320). The Light Course (Anthroposophic Press, 2001).

XXIII. (NA) Geisteswissenschaftliche Impulse zur Entwicklung der Physik. Zweiter

naturwissenschaftliche Kurs: die Wärme auf der Grenze positiver und negativer Materialität, 14

lectures, Stuttgart, 1920 (GA 321). The Warmth Course (Mercury Press, 1988). This Mercury Press edition may still be in print.

XXIV. (NA) Das Verhältnis der verschiedenen naturwissenschaftlichen Gebiete zur Astronomie.

Dritter naturwissenschaftliche Kurs: Himmelskunde in Beziehung zum Menschen und zur

Menschenkunde, 18 lectures, Stuttgart, 1921 (GA 323). Available in typescript only as "The

Relation of the Diverse Branches of Natural Science to Astronomy."

XXV. Six Lectures in Berlin, Cologne, and Nuremberg from 1906 to 1911, (Misc. GA's.)

The Education of the Child — Early Lectures on Education (a collection; Anthroposophic Press, 1996).

XXVI. Miscellaneous.

~^~

List of Steiner Reviews: Click Here!

Any questions about this review, Contact: Bobby Matherne

To Obtain your own Copy of this Reviewed Book, Click on SteinerBooks Logo below:

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

22+ Million Good Readers have Liked Us

22,454,155

as of November 7, 2019

Mo-to-Date Daily Ave 5,528

Readers

For Monthly DIGESTWORLD Email Reminder:

Subscribe! You'll Like Us, Too!

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

Click Left Photo for List of All ARJ2 Reviews Click Right Bookcover for Next Review in List

Did you Enjoy this Webpage?

Subscribe to the Good Mountain Press Digest: Click Here!

CLICK ON FLAGS TO OPEN OUR FIRST-AID KIT.

All the tools you need for a simple Speed Trace IN ONE PLACE. Do you feel like you're swimming against a strong current in your life? Are you fearful? Are you seeing red? Very angry? Anxious? Feel down or upset by everyday occurrences? Plagued by chronic discomforts like migraine headaches? Have seasickness on cruises? Have butterflies when you get up to speak? Learn to use this simple 21st Century memory technique. Remove these unwanted physical body states, and even more, without surgery, drugs, or psychotherapy, and best of all: without charge to you.

Simply CLICK AND OPEN the

FIRST-AID KIT.

Counselor? Visit the Counselor's Corner for Suggestions on Incorporating Doyletics in Your Work.

All material on this webpage Copyright 2019 by Bobby Matherne