~~~ Tidbits of Memory: Annette & Buster Remember their Life ~~~

A Collection of Memories from Annette and Buster Matherne

Recorded, Transcribed, and Edited by their son

Bobby Matherne ©2003

Site Map: MAIN / Tidbits / This Page

A Collection of Memories from Annette and Buster Matherne

Recorded, Transcribed, and Edited by their son

Bobby Matherne ©2003

Annette Mae Babin Matherne remembers her early life in Donner, among other things. Hilman Joseph “Buster” Matherne remembers his early life. These memories were recorded, transcribed, and word processed by their son, Robert Joseph “Bobby” Matherne, in the Fall of 1999. Photo Taken Fall of 1999, around the time they told these stories.

Clicking Here!

== == == == == == == TABLE OF CONTENTS== == == == == ==

First Interview with Annette

Oral History, Part ISecond Interview with Annette

Oral History, Part IIBuster Remembers

Recollections by Hilman Joseph MatherneHow Donner Got Its Name

A Story by Leah Durkes EsteveThrough the Sawmill Town of Donner

A Song by Bobby Matherne== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

FIRST INTERVIEW, NOVEMBER 4, 1999:

== == == == == == ©2003 by Bobby Matherne == == == == == == == == ==

This is a transcription of a video tape of Annette Matherne. It contains her early memories of growing up in Donner, Louisiana, among other things. She talks some about her life in Westwego and has stories about Nancy Matherne, Odette Clement, Lillian Bonvillain, Lydia LeBlanc, Elaine Orgeron, and Carolyn Matherne, among others. All material without quotes was spoken by Annette. Bobby's questions are in quotes. Buster's words are prefaced by [Buster] and appear also in quotes. I have endeavored as much as possible to transcribe exactly Annette's words, without deleting an extra word or changing words to "fix" the grammar. This is the way my mother talked all her life, and, as a first generation speaker of English who never went to college, she did pretty well. She was almost 82 at the time she did this interview. There are gems of little stories in this interview that will repay anyone who takes the trouble to read entire text. This has been a labor of love, a labor that I can feel in my wrist and fingers as I type these prefatory notes after completing the transcription, and, more important, a love that I can feel in my heart. Thanks, Mom! Anyone that reads this material and has information to add to or help fix some error of fact, I'll be glad to receive it and incorporate it appropriately into the material with credit. Email it to Bobby Matherne by Clicking Here!

[Note: After the long interview with Annette are some memories that Buster wrote down, which are included in full. ]

In 1918, right before the war ended, I was born in a little cypress sawmill town called Donner. I was born Jan. the 28th 1918, and I was the seventh child of Pierre Gabriel Babin and Daisy Himel.

There were six children born before me: Lillian, Dio,

Lester, Mamie, Odette, Charlton, and then I was born. My mother had 12 children altogether - Charlton died at the age of 6 and Mamie died at 3 months old of pneumonia.

My dad was the operator of the little planing mill - he used to tend to the mill and start it off in the morning.

I started school when I was five years old. The year after I started school we had a hurricane. That was 1926. The whole school was demolished; they had to build a new school. My teacher was Ms. Claire Ledet in the first grade.

My earliest memory is: I fell, we were playing hide and seek. Those big cypress roots used to stick out of the ground in front of the cypress trees in the yard, and we'd use that as our base. I was running to the base, and I fell over and knocked all my front teeth out. Our principal then it was Ms Ingrid Petersen. She came and took me to the doctor and brought me home. She was carrying me in her arms when we got to the door. It was the day after Mazel was born, and Mom didn't know what happened to me - she was kinda shook up. Ms Petersen said, "Don't worry, she's all right. She just has a few teeth knocked out." (Laughs) I looked a sight for awhile, but they grew back.

I was sort of a little tomboy, like I used to wear overalls and I borrow my brother's BB gun to try and shoot birds. Mom and Dad had always made a big garden. I used to always be out there helping them in the garden, because my sisters didn't like to be outside. So I ended up working in the garden. Mother always had her own cows because we needed milk. I used to go bring (sic) them to pasture - it was about two blocks away from the house - and I had to go bring them down that lane and put them in the pasture. Sometimes it was so muddy and soggy, that I to put knee boots on and I would sink all the way to my knees with the boots on bringing the cattle to the pasture.

We had a lot of fun in Donner because there was a lot of things that we played, games. We had old steel wheels that we used to get from ... Daddy used to get them at the mill. They'd throw them away after they'd change them. We to get a piece of wire and make an indention (sic) around the wheel, and leave a handle on it. Then we'd wheel them down the road. We'd have fun going running up down the road to see who would get the furtherest (sic) before their wheel would fall ov . . . fall down.

We also had a lot of what you call "China ball trees" - they bloomed the prettiest little purple flowers, and you could pull them out one at a time and make them into chains during the summer months. While we were in school, we had a lot of fun playing marbles. We couldn't wait for recess to come, and everybody would bring their bag of marbles to school. We got bawled out if we dropped any on the floor during the school class room. (laughs) It was a lot of fun because I haven't seen a child in this age sitting down playing marbles, which is a very nice game. Even the adults used to play with us some times.

"Did you play for keeps?" (Bobby's voice in quotes.)

Oh yes.

"How did that work?"

Well, if you, I don't know how many you had to hit in the ring, but you'd win the whole ring, whatever was in the ring. If anybody would hit a couple of them out, they would keep them. But, after, if you were the last one to shoot, and you shot one out the ring, well, you got the rest that was left in the ring. So, it was like a big ring that we would make.

We had a lot of a fun fishing around Donner. Donner had a lot of fish around the area because it was a cypress town, and we had a lot of bayous that went back and forth to the planing mill. Right back of the mill, where they would haul in the logs, there was a big pond, and my neighbor's daughter, Nettie Bonvillian, would call me all the time. She would say, "'Nett! You wanta come fishing?" I said, "Yeah!" And I'd grab my fishing pole, we'd go. And we'd always comeback with a big string of perch. They were beautiful!

"Was that Dennis's sister?"

Yes, that was my brother-in-law's sister.

"So, he and Lillian knew each other from a very early age."

Yes. Yes. The year after it they (Dennis's Family) moved from Donner, Lillian had went (sic) to my uncle's house in Marrero, Uncle Bill's house, to spend a week, and they (Dennis and Lillian) ran off and got married. Then they called Mama. Because his sister Nettie was getting married (laughing), he said he wasn't going to dance bare feet at his sister's waiting. Which happened to me at one of my sisters weddings.

"You actually danced barefoot?"

No. I skipped out and they couldn't find me. I went to the show in Thibodaux while the reception was going on. (laughing) But... we had a lot of fun in Donner. We also had basketball teams - we couldn't wait for lunch-hour to run and play basketball. Also during blackberry season, we had a big railroad track that was passing right in front of the school house, and they had blackberry vines like crazy along there. And during lunch hour, well, we would go home to eat, go eat and come back, so we would take blackberries going back to school. We would go in and teachers would know that we picked blackberries 'cause our tongues were all purple. (laughing)

"Did they not like you to pick blackberries?"

They didn't stop us from picking blackberries.

"But they could tell."

One thing: whenever there was any disciplinary (sic) to be done, we had these yellow daisy things that grew in the schoolyard all over the place. When somebody did something they shouldn't have done, she'd make you go pull either fifty or a hundred and put them in a pile. Then she'd stand by you and have you count them (laughing) - see how many you had in that pile. That was a lot of fun. It was something, I'm telling you: the kids hated that.

<pause>

Our school went through the 8th Grade. After 9th Grade, we had to go to Houma to Terrebonne High. That was the only high school in the parish. We used to drive over a gravel road all the way to Houma and back to Donner. We'd leave at 5:30 in the morning and didn't get home until 5:30 at night. Had to take a bus early in the morning.

"It must have been dusty at times."

It was it was dusty -it was an old gravel road and bumpy, and - y'all complain, the kids complain about school buses now, y'all should have rode all in some of the buses we rode on. When you would walk into the bus the seats would go across on each side. You had to sit in the middle or sit by the windows. That was the most horrible drive, back and forth to school. And, of course, we didn't complain because at least we were getting an education - those that wanted an education went. There was a lot of them that didn't make it. It wasn't compulsory that you get a high school education.

"Were you speaking French before you learned English?"

No, I didn't speak French at all. I spoke a few words to my grandmother, because she didn't speak English at all. But I had to struggle to save a few words that I did.

"How about Lillian?"

Lillian knew because Mama didn't know any English until Lillian started school, and she started to learn from Lillian and Dio. By the time she got to me, she knew enough English that she never spoke French to us. So that was the thing. But a lot of people didn't know how to speak English at all, they would just talk French, there was a lot of French-speaking people in our area.

We also had, like . . .they talk about segregation today. We were segregated in our little town. There were the wealthy, the next-to-wealthy, then the Italians, then the Colored. We had the rich people living in one area, we called them rich people, and us poorer people lived in another area, and right next to us they put the Italians, and next to the Italians they put the Colored, the Blacks. So if y'all think segregation's bad, it was bad in those days. Half of the people wouldn't let the Italians children play with their children. And Mama said, "They can come anytime they want to." My friend, Anna Mae Scaruffi said, "I always remembered your Mama because she said, 'You come over and play with my children anytime you want to.'" And today she's still says that to me, "I appreciated that so much."

<pause>

"What kind of jobs did the Italians do, and what kind of jobs did the Blacks do?"

The Blacks did most of most of the logging, and . . .

"cutting the trees?"

They did most of the hardest labor, in the Italians Anna Mae told me what her Daddy did, now I forgot, but Daddy ran the planing mill, and the others, the richer ones worked in the office. They were considered the wealthy. And we had a doctor, a family doctor, a company doctor. The first one was Doctor Lehman. He was the one that delivered me. And then Dr. Kleinpeter came to Donner. And he said, "Anytime y'all want to come use the phone, call Thibodaux, y'all can come use my phone. I have a direct line to Thibodaux." So, he was very nice. And his son graduated the same year I did, and he's a doctor still in Thibodaux. And Mannie D. Payne was a doctor, and he's still in the New Orleans area.

Then we had our dentist, Dr. Thibodaux, who is still a member of our Donner congregation. We meet with him every year. He graduated with us. And we were the two artists in the bunch. We loved to draw. We would talk at all the Donner reunions about the drawings. And I still like all that - I like drawing, I like quilting, I make pine needle baskets, I do knitting, I do crocheting, and I learned all this from my parents. We used to do a lot of quilting in Donner on those old frames. I remember my grandmother and them - they'd sit down and quilt, and they'd invite all the people in the neighborhood to come over - it was like a big day - they'd bake cakes, serve desserts, and everybody had a quilt day to put their quilt on the frame.

And today, well, I belong to a quilting club. I was trying to revive some of it in the area. I got a few of them interested, and they are very good quilters today, so at least I'm passing some of that on to the next generation.

"Why don't you talk about this one. This is one the you just finished, isn't it?"Yes, this is a Three Bear quilt. The Three Bears - the baby bears. And this will be for one of my grandchildren. I've given one to almost every one of my grandchildren when and they had a baby. This is a baby quilt. And I've quilted one large quilt for almost every one of them, too. So they all have some kind of memory of my quilting.

"Talk about the quilt you did when you were twelve."

Also I did an applique quilt, when I was 16, and I I'd seen some pictures, some patterns on the Times Picayune - it was back in 1934.

Patterns were coming out in the paper every day, so I would cut them out and save it. Mama said, "Well, I'll buy the backing, and if you want to start, we have got enough scraps to do the applique. And it was all bouquets of flowers, each center was appliqued on with different flowers in the center of each of twelve blocks. And it won two blue ribbons at the State Fair in Donaldsonville. And I still have the quilt today - Mama gave it to me and I passed sit along to my daughter, Janet, about two years ago. I let her have it - I said well, it'll go down in the family. And I think I'm going to leave JoAnn have it for her museum for a couple of months. She wants to put it in her museum when she opens it up. She is supposed to call me about it.

Also, when, during this summer months Dad and them worked at the planing mill. Daddy and my brothers, Lester and Dio. And we used to go bring them their lunch in a big straw basket with a handle on it. Mama would fix a hot meal, and I'd carry it to the mill for them. We would pass through the lumber yard where they stacked the lumber to dry , and go walk and bring it to them. When we would come back, we would sit under the lumber stacks and eat what was leftover. (laughing) . . and enjoy a little rest because it was so hot. (more laughing). We thoroughly enjoyed that. It was like a picnic every day.

"You said, 'planning mill,' but is this where they shaved the wood boards to make them smooth?"

Where they make the boards, where they make the moldings . . . 'cause my dad also made it be in knives for the molding machine.

"Did they use tupelo gum for the molding?"

No, they used cypress, tupelo gum they just made boards out of them. [Bobby Note: My research of the time indicates that tupelo gum was only used for moldings and were shipped all over the country. Cypress on the other hand was mainly used for board stock. Note she continued to use "planning" for planing throughout all of the interview, so I corrected it from the beginning.] Lester use to work back of one of the machines that did the planing, him and Uncle Louis. They would be one on each end, one pushing the board through and one catching it and stacking it on a train dolly. They had little tracks that went into that part of the mill. They had the train dollies there, and they would just put the lumber on them, then they would take them out to the lumber yard and stacked them out there.

"Was that Uncle Louis Himel, your mother's brother, Earl's father?"

Yes, we used to call him Paràn. My grandfather and grandmother, Silvani Himel and Azelda Himel, lived three houses away from us. He used to work at the mill, too, but he got rheumatism, at least that's what the doctor said, in those days, he got rheumatism so bad he couldn't walk anymore. So Grandma sewed, she was a seamstress for the wealthier people in the town, the Gilberts, and the Kellers, and the . . . uh, I can't remember the other people, but she did seamstress work for them.

<long pause>

"Did you have electricity in your home when you were a . . ."

Oh, well that's another thing, electricity was, we called it "electric lights" - they didn't have, we couldn't put too much on the lines, it was just mostly for lights. They ran a light system through the town in everybody's house, and they would put the lights on at 6 PM in the winter time and 6:30 in the summer time, and they would stay on until 10 o'clock at night. If you didn't finish your homework by 10 o'clock, many a time I set by lamplight to do my studying because the lights had already gone out. I had a lot of studying to do when I was in high school.

"Did you had anything else that used electricity back in those days?"

No, they had a few people who owned, I think, an electric iron, maybe. One of two people that owned electric irons maybe, but we couldn't afford that.

"So how did you do ironing then?"

We had an iron made out of cast iron. And we used to heat them on the stove. And we had to have some beeswax to rub our iron on, and smooth it off on the cloth before we would iron with it. I still was using those irons when we got married. I'm sorry I'd didn't keep any, because they are relics now. And pots, the same thing, it was all cast iron pots. You didn't have no aluminum or nothing out in those days. It was all black pots to cook in.

"And you were cooking on wood stoves?"

It was all wood stoves. That was another thing. With the wood, the mill used to. . . whatever end they would chop off, the end of the pieces, they would put them in trucks, and delivered a truck load for 50 cents - they would dump it in your yard. For 50 cents you had a whole truck load of wood. Daddy and them used to cut down a couple of trees for the bigger pieces to put into our heaters. We had these potbellied heaters.

"How big a house were you living in?"

We lived in what you call a shotgun house. We had, let's see, one, two, three, three rooms and they added a big kitchen in the back.

"Outdoor bathroom?"

Outdoor baths, we didn't have a bathroom in the house, we had to use an outside commode - that's what we called them.

"And you bathed in No. 3 tubs?"

And bathed in big galvanized No. 3 tubs. Every time we would take a bath we had to haul the tub out in the cold weather, whatever it was.

"Did you have water coming into the house?"

We had water coming from the cisterns, and Daddy piped them to the house, yeah, they did that. But we would run out of water, and we would have to get water from Houma. They would come with big tank cars and fill up our cisterns. And we had to pay so much for that. I don't remember how much Dad paid to have our cisterns filled. But we used a lot of water from the bayous and everything. We had a deep well by the garden to water the garden with. So, that was a big help. And then, the company ran a water line across almost every street, but you had to walk a piece to get the water, you know. To bring it to water your flowers and everything. And that was all swamp water.

"Did you have sidewalks, from house to house?"

We had walks but they weren't sidewalks, they were plank walks. We called them plank walks. It was boards they'd use, and they'd build us plank walks.

"Raised off the ground?"

Yes. Raised a piece off the ground. Just about that high (Annette gestured about 4 inches with her hands.) Just a board to hold them, a 2X4. We had board walks all around our house. Then we had to scrub all that every Saturday. Get some water and soap and scrub the banquettes from the front to the back.

"They got muddy?"

Sure they got muddy - you walked off that road, it was a gravel road. And if you went in the garden, and came out of the garden, it got all over the place. It was a lot of things that we

did. Scrub the porches. We all had front porches, and we would scrub that with bricks sometimes. Saturdays. Get down on our knees and scrub that every Saturday morning.

"How about newspapers? Did you have a newspaper?"

Yes, we had the New Orleans States. My cousin Earl Himel delivered the paper for us. He was the paper carrier. He bought his first bicycle from delivering newspapers. Earl lived . . . Earl's parents died when he . . . must have been 12, Charles was only about 10, I think, when his mother died. They lived with my mother after that.

Then, in 1935, I graduated from Terrebonne High. It was the year the mill closed. And my dad heard about this farm in Bourg that was up for sale, so he went and bought it. And I didn't want to go to Bourg with them. I said, 'I am gonna go see if I can find work in New Orleans.' So Lillian said 'Come by my house.' So I went by her house.

"Where did she live, in New Orleans?"

She was living on Avenue E.

"So they were living in that Avenue E. house back in 1935?"

Yes. . . No, they lived on Louisiana Street when I went to live with them. And I had to walk... Ooh, say half a mile, up to the railroad track, cross the railroad track to catch a bus to go to work. And that was early in the morning. I started working for Lane's Cotton Mill.

"How did you get there? You took a bus to where? You took a ferry?"

I went to... I walked up to the tracks in Westwego, I'd catch a bus, and we go all the way to Marrero, and cross the ferry in Marrero at Napoleon Avenue, 'cause it was right on the beginning of Tchoupitoulas, Lane's Cotton Mill was.

"Could you walk to work from the ferry?"

Oh yeah, everybody walked. I worked there for five weeks, 5 ½ days, and I was making only $5.50 for the five and a half days that I worked. Barely paid my ferry fare and bus fare. Then I started getting piece-work.

"So they paid you how mucha day?"

In piece-work . . . I don't remember how much they were paying us per bolt, but I'd make 17 to $18 a week on piece work, more than my Daddy was making at the mill. So you can about guess how much they paid them at the mill. Of course, in those days it was a lot of money.

"Recall the bus trip from Westwego to Marrero - was there a Celotex plant at that time or an open field? "

No, they had the Celotex plant because Dio was working there. Dio left Donner, went to Chacahoula, and then he went work there. No . . . he went straight to Celotex when he left Donner, because he left Westwego and went back to Chacahoula after.

"So what did you do after that? What were you doing in the Cotton mill? "

I was selvedge hand. I was pulling the selvedges through the warps, on the big warps, the little thick part on the material, you call that selvedge. Well, I had a hook, a special little hook, you had these reeds, these needles that were hung on racks, three or four racks of needles. You had to count them, one, two, three, and you had to know exactly which one you had to pull that thread through if it was broken. Cause when it was broken, you had to make a weaver's knot, and pull the thread through.

"So the machines would run automatically until something broke?"

Yeah, it was like a wooden shuttle that would shoot back and forth, weaving it. You had to crank a handle. Then you had to tell the loom fixer what was wrong with the loom to fix the loom cause they didn't know. They come there, "What's wrong with it?" So you had to know was wrong with your machine for 'em to fix it. I'd say, "the shuttle needs to be sanded, or something. It looks like it was catching the material or something." And they'd sand the thing. Or if there was something wrong with one of the needles, they'd fix it. But, most of the time, you had to tell them what was wrong with your machine.

"So what did you do during your time off while ya'll were working there?"

Aw, on Saturdays, my cousin Ethel Cancienne, they were living in New Orleans then, and she was going to Soulé's. We used to meet every Saturday morning - we'd go to two shows, bring our bathing suits, and go to Audubon Park and swim until nine o'clock at night. When they would close the pool, we'd leave and come back home.

"What theaters did you go to back then?"

The Saenger and the Orpheum. Sometimes the Loew's.

"You remember any pictures?"

I really . . . it was so long ago, I don't remember that.

"Any movie stars you remember from those days?"

Barbara Stanwyck. Errol Flynn. I can't remember too many of them. If I'd be Barbara, I could remember them, my sister-in-law, she knows, oh, she can remember names, it's something I'd never paid too much attention to. <pause> I'm trying thing to - I can't remember too much more.

"How many children did Lillian and Dennis have then?"

They had Rosemae and Sonny. We used to help them with their math, algebra, but math mostly, they weren't in algebra yet.

"So you decided to go back to Bourg?"

Well, Mama wasn't feeling good. I said, "Well, I think I'm going to go back in help her awhile." Oh, talking about that, I got to come back to one of the days while we were still working at the mill. Dad was going to dig potatoes. I had never seen them dig potatoes. You know, I'd helped Daddy with a pitchfork in the garden. He'd pitchfork them and I'd pick them up and put them in a bucket, but I'd never seen them done with a plow. So, I'd told Odette, "I'm going home this weekend, I'm going to help Daddy with his potatoes."

"Was she working at the mill with you?"

Yes, she worked at the cotton mill, too.

"Where was she living at the time?"

She was living with Lillian, too. So, she said, "Okay." So, I went home. I put old jeans on, I went out there. Dad was opening the rows; it was so pretty to see those potatoes falling out. I'd get on all fours - I was picking 'em up and putting 'em in the bucket, and I kept on. So Sunday morning, I was so sore! So and I got home, and I had to go to work that next night, cause it was night shift, Odette was coming off of day shift, cause it was during the war - Odette was coming off of day shift and I was getting ready to go in, she says, "You look terrible - what's the matter?" Cahw, my legs hurt so much. She says, "Come on back home, don't go to work, you crazy?" [laughs] So so I went home and rested that night so the next day I felt better. That was an experience! But I enjoyed it so much!

"How did you get from Westwego to Bourg in those days, what kind of car, how did you go?"

We caught buses. They had a transit bus that went all the way to bridge circle from Westwego. [Note: The Bridge Circle Inn, where the buses stopped, is no longer there.] From there, we'd take a bus to Houma, and Dad and Mom would pick us up in Houma. I did that when ya'll were children, you and Paul. And I swore that was it! Buster and I! [laughing as she talks] We had four suitcases, cause it was winter time . . .

"Ya'll went on a bus ride when I was a baby?"

Oh yes! How you think you'd get anywheres? We didn't have a car until after Steve was born. I think Steve was a baby when we bought that car. That first Chevrolet. I said, "I'm not going back to Bourg."

[to Dad] "You don't remember when you got that first car?"

[Dad] 1940 Chevrolet.

Somebody from Tennessee owned it. That's who we bought it from.

[Dad] I paid more for it when it was four or five years old than it cost when it was brand-new. That was in the middle Forties.

No, Paul was a baby. That was in 1942.

[Dad] Cause I was working at Nine Mile Point then.

Yeah, cause I told him, he used to have to walk all the way from Westwego to Nine Mile, you remember, you used to have to walk that to work. And I told him, I said, "Look, that's enough of that! Let's try to get us a car. You got to stop that long walking.

"So tell me about the bus ride. How old was so I when you went on those bus rides to Bourg?"

Well, Paul was about a year.

"So I was about three?"

No, Paul wasn't a year old. I was pregnant for Steve. Paul was a baby. And I'd told him, never again. Too much - totin' stuff and all that.

"Was that around Christmas time?"

Then I went one time without your Daddy. You were a baby. And he had to work. And I swore I'd never leave him for Christmas after that. Cause it was so lonesome when everybody else is together and here you are with just me and Bob there. So I told Mama, "We'll come visit you Christmas evening, but I'll never come on Christmas Eve again." And Janet was born December 5th, and when, the night, well, she was still just a few weeks old Christmas Eve, my neighbors came and they sat in front of the house and sang Silent Night - and Buster, your dad, was working shift work, so another Christmas Eve [laughing] I sat with just you and the children, listening to the carols. That was Dr. Wells, you remember the Wells that live next-door? Rev. Wells and his wife?

"Carol Wells, the son? I remember going to Assembly of God summer school, bible school, with Carol."

They were some nice people.

"Where did everybody sleep? I know how small that house was in Bourg. It seems like you only had a couple of bedrooms. Three bedrooms? "

You mean Mama's house? You talking about the old house or the new one? Cause when they moved there, they had the old upright siding, no, no, wasn't sealed inside, it was an old, old house they bought, they lived in there two years.

"Did they tear it down and build the other one?"

They tore that one down and built another one. They lived with Grandma until that house was built. The original house, the one in Bourg that's still there, well we had beds in every one of the bedrooms, and then the big couch in the living room was a day bed. So they had a lot of room. And, if there wasn't enough room, we'd throw something on the floor and then sleep on the floor.

"I remember the feather mattresses."

Yeah.

"What was the first wedding they had there? I remember Clarise and Tee-Al."

Yeah, Clarise and Tee-Al. They had that outside in the yard.

"Was that after the second world war?"

Yeah, cause Tee-Al was in the service.

"Sailor?"

Mm-huh. He was in the Navy. He used to go down in the submarines. That's why today he couldn't go down in any kind of closed area. He said he did that so much during the war that he'd get, how you call that when you get . . .

"Claustrophobia?"

. . . claustrophobia. He'd get claustrophobia. Yeah, he was an electrician, huh? [implied question directed to Dad, who was in the room during interview] Tee-Al? Wasn't he electrician, or was it Purpee that was an electrician?

"Purpee was an electrician."

I think Tee-Al was too, he was in the submarine.

[Dad] "I guess, I don't know."

"So when Grandpa bought the farm, you lived off of income from the farm?"

Sugar cane. He planted sugar cane. And a few potatoes for his own use. Plant some green beans. So some beans, too, at the market. Cause we went and helped them pick beans a few times after we got married. Planted beans, he planted potatoes, but he had a lot of sugar cane.

"Had a bunch of chickens too, huh?"

Aw, they just raised chickens for them. Her own use. They always had cows. They had two cows.

"And they used to slaughter pigs?"

Oh, well, in Donner, too, we always had a pig. We'd raise pigs, and around November.

"Did he raise pigs at the Bourg house?"

Yeah, we used to have a boucherie in November. We used to call that "boucheries." We'd have a big boucherie every winter, in the fall months. During World War II, they pickled all their salt meat cuts - you could not buy stuff like that, so when they slaughtered a pig, they pickled it down. Put it in big crocks.

"Fill it with lard."

Yeah, they'd render the pork rinds and use the lard, pour lard over it.

[Dad] "Butter."

Make your own butter. I still have Mama's original butter churn. This came from Grandpa Matherne's store. This butter churn I have. Cause when Buster's Daddy was getting ready to close his store, he said, "Buster, you want that butter churn?" He said, "Yeah, I'm gonna give that to my mother-in-law." I still have its sitting on the counter there.

[Dad] "Before that, they used to put the Cream in a quart jar, and shake it until it turned to butter."

Oh, yeah, we had to shake it in a quart jar, and we'd shake, and shake, it took a while before it turned into butter. But

that's the way we originally made butter. I made quite a good bit after we were in Westwego, because we could buy the pure milk then. And we had about two inches of cream in every jar. I'd spoon it out, put it in the jar, and I'd make my own butter.

"I know you used to make creole cream cheese. How'd you do that?"

Well, whatever milk would turn sour, you just put it in a dish and let it clabber. Clabber overnight. And you poured it in a cheese cloth or any kind of cloth that was kinda thin, muslim would be fine, too, make a little bag, and pour that in it, and let it hang. All the water would drain out, and you'd pour it in a bowl, and there was the cream cheese.

"Will that work with homogenized milk?"

I don't know, I've never tried it. I don't know if you can buy pure milk anymore. They don't sell it unless it's pasteurized. So, I don't know if pasteurized milk will do it.

"Only place you can buy Creole Cream Cheese anymore is Dorignac's. Since they closed down the Borden's plant, you can't buy it in the supermarkets anymore."

Yeah, that used to be the best, the Borden's.

"Okay, let's talk about: you went back because your mamma was sick, Grandma Babin was sick, was that just temporary, or she got better?"

She had a little touch of malaria.

"How many kids were still living at home when you went back? Was Merlin a teenager then?"

There were five of them left. Cause I was the sixth. Let's see, I was the seventh, then there was Zelda, Mazel, Clara, Clarise, and Merlin still home. Azelda was getting ready to graduate . . no . Azelda graduated and got married before I went back home. We even paid for some of her . . . Odette and I put in together and bought all her stuff she needed for graduation. Bought her prom gown, her shoes, and everything. Cause she got married right after she graduated. And the year after that, I came to Bourg, when we got married, Daddy and I. I came back in January. And I met Daddy at . . . I went with one of the neighbors to Bourg to a basketball game. We went to the Post Office, because we didn't have mailed delivered then, we had to go to the Post Office to get it. And so we walked to Bourg, got the mail, and went to the basketball game. Your daddy came up and asked me to hold his wrist watch until after the game. He was . . .[laughing] . . .

[Dad] "It was our first date."

Yeah, and he asked to walk me home.

"Was he playing basketball?"

He was coaching it. And so he came and walked me home. Then after that . . .

"Did you introduce him to Grandma and Grandpa then?"

Yeah.

"Did y'all shop at Grandpa's store?"

Yeah. Then he asked me if I was going to the dance. I believe that was at the American Legion, huh? [to Daddy] and that was the first date we had together. For Mardi Gras, right before Mardi Gras. Right before Lent ended (sic), because everybody goes to a dance, the day before Lent ends (sic, she meant the "day before Lent starts"), after that you can't go. We wouldn't dance anymore during Lent; nobody could dance during Lent. [laughing] That was a big penance. [Note the ambiguity: not dancing was like a penance, and if you did dance, you had to confess it, and that brought a big penance, like 25 Hail Mary's or a full rosary to be said.]

"So, where did you get married at? The old St. Ann's church?"

Yeah, we got married in Bourg, St. Ann's church, Father Schexnayder."

"Oh, and for a reception, what did you do after?"

We had a reception at Mom's, outside, like we had for Clarise, under the pecan trees. Carolyn was about 18 months old; she was young. Carolyn must be going on 62, huh? How old are you?

"59. She's three years older than me."

She is 62 then. She made 62 in July. It's gonna be 62 years we were married; she was just over a year old, walking all over when we got married.

"Who stood in your wedding? Who was the best man? "

Lester and Eddie, and Elaine and Alicia. Elaine and Alicia stood when we celebrated our 60th.

"Where did ya'll live at first? Was Daddy already working at the time?"

Daddy was working for Autin's Packing Co. And he used to ride with Daddy [Peter Babin] to Houma every day. . . [to Buster] You used to go with Daddy to Houma every day? [no response, Buster's hearing is poor even with the hearing aid, she repeats question, louder this time] How you used to get to Houma every day when you worked at Autin's? With Daddy?

[Buster] "Daddy'd pick me up."

My Daddy would pick him up and take him to Autin's every morning. Well, right before we got married, his Daddy had a little barber shop, on the side of the bayou across from their store, where he used to cut hair, and he told Buster, "I could fix that shop - add a little room for the kitchen." So that's what he did. He fixed that up, and we rented that from him when we first got married. Then we moved to West Main in Houma. Rented two rooms from a Mrs. Babin. No relation, but, she was a widow, lost her husband. Then, before you were born, we moved to the street right there where the slaughter house was, Autin's slaughter house was down that street, he [Mr. Autin] had a couple of houses he had built for his employees. We rented one and moved into it. It was a three room house. And then, from there, we moved . . . Buster quit working for them, sued Autin's for back pay, and went to Westwego, uh, Marrero, we lived with Odette for about six weeks, and then we got a house on Avenue F. Rented a house on Avenue F, no, it was Avenue E. We built a house the year Paul was born on Avenue F, and from there we moved here [304 Mimosa St, Luling].

"Wait, you said you lived with Odette? I thought it was Hilda."

No, I lived with Odette - Hilda lived with us while we were building, and they kept the house we were living in, when we moved.

"Oh, so you rented half of a double shotgun house on Avenue E, Aunt Hilda lived with you, until you moved, and then remained there in the house they lived in for so long?" [until 1960 or so, as best I can remember]

Yeah, Slim couldn't hardly make a living on just working on farms around Bourg. He'd get little odd jobs. We kept saying, "Why don't you come to Westwego? Get a job somewhere around Westwego. So he came and went to Rheems and put his application in, and got hired. So they moved in with us until we got finished building our house."

[Buster] "That's the only job he ever had. He retired from there."

And he stayed with them all that while.

"Was Lydia living there at that time?"

No, she moved in later. [Lydia lived in the next double towards Fourth Street, across the alleyway. ] Lydia lived with, was it Hilda? When she was going to Ochsner's, [to Buster] to study to be a technician? I believe so, she was living with Hilda. Either Hilda or Elaine, I don't remember which one. But I think she was living with Hilda.

<pause>

"What was it like, having your own house?"

Aw, it was nice! To tell you the truth, when we built our house, Daddy had, we had, I can't remember how it was, what we had saved, it wasn't much high no, it was just enough to pay for our bathroom fixtures, cash. But we did get some money from Autin's, so it paid for the lot, and we made a loan for $1000.

[Buster] $891.

Eight hundred and ninety-one dollars. We had enough to pay for the house with that, pay the carpenter, build a four room house, two bedrooms, a bath, a kitchen, and a living room, and a little porch in the front. And 300 dollars for the lot, which was a little over a thousand something dollars. About 1100. We built our first house.

"Did you have neighbors on both sides?"

Oh, yeah. We had Nat Lee, Mr. Nat Lee was living next to us [the side towards Fourth St]. And the Robichaux's on the other side.

"And Aunt Lady, was she living there at that time?"

Oh, yeah. That's who we got the lots from. I think it was her that own . . . was it Uncle Lucius that owned those lots?

[Buster] No, it was a friend of his that had moved away. He gave him the power of attorney to buy [sic] it.

If we wanted to buy it.

"Was Paul's Motors already there across the street?"

No, it was built after. There was nothing - it was just a pasture out there.

"I don't remember that."

Paul's Motors built not too long after we built, but they weren't there when we moved there.

"That's why we don't have any pictures of it then, cause we didn't have anything to take a picture with."

Nope. [laughing] And then we couldn't afford to take too many pictures. [more laughing] We had a little-bitty old Brownie camera. We used the heck out of that.

"So, when you went shopping - got dressed up to go shopping, where did you go?"

Well, I didn't have to shopping too much, the grocery used to deliver the groceries to your house. Just call them on the phone, and they'd deliver it. Or sometimes Daddy would go and pick them up. But, if we wanted to do any clothing shopping, we'd take the bus. Go to Gretna, or go across the river in New Orleans.

"I remember you taking me on Sala Avenue, so you did some shopping on Sala Avenue?"

Yeah, Merlin's Shoe Store, Rubenstein's, I believe, was the name of the clothing store.

"And, you remember the first library? On Sala Avenue? Remember taking me there?"

Yeah, mhm.

"How old was I?"

You must have been only about three or four years old. Cause I used to bring you and leave you pick out the books you wanted.

"So, did I start reading before I went to school?"

I don't remember, Bob. You knew your alphabets and your numbers.

"About how old was I when Maude [Boudreaux, of Paul's Motors] gave us that box of books?"

I don't remember about how old you were, Bob.

"You remember when she brought the books over?"

Yeah, I remember that. Those books. Children's books. It was something she got in the Parts place, they had given 'em to them.

[Buster] "You must remember when we used to go to Lake Pontchatrain and throw a cast net?"

"Yeah, I do."

[Buster] "And catch a bushel basket of shrimp in one evening. We used to go at night."

"Used to stop and buy some clams and a ball peen hammer, and our job was to smash the clams, and you would throw them in the water to attract the shrimp, right?"

[Buster] "You had to crack them. I had made a ramp, so we wouldn't have to get down where it was slippery. It was easy to throw. We'd really had . . . we'd go pretty regular. We'd come back, after we'd boil the shrimp, save the hulls and make shrimp dust. And then take corn meal and cook it with the shrimp dust and make balls. And throw that instead of the clams. They'd go for that.

"You had to dry the shrimp hulls?"

[Buster] "After it's boiled, dry them and then you'd beat 'em."

"You mixed it with what?"

[Buster] "Cornmeal."

You'd put the shrimp dust in the middle of the ball, and roll 'em up, you know, like a little . . .

"I just barely remember that."

Yeah, and we'd throw 'em in the water. The shrimps used to come for that.

[Buster] "Sometimes we'd take a can of dog food, punch holes in it, and throw that out there."

"I remember you knitting cast nets."

[Buster] "I used to make them myself. I used to make crab nets. We'd go crabbing off the seawall, too. Beautiful crabs."

Beautiful, golden fat in them. They were the color of gold inside of 'em when you'd open 'em up. So beautiful! And we took ya'll on many a trip out to the lake, too. Lakefront, when they still had the Pontchatrain Beach. Carolyn! Carolyn would come back from work, "Ya'll ready, kids?!" [laughing] That's all she had to say, ya'll'd put on your bathing suits, grab a towel, and we'd take off. Cause most of the time your dad was working and couldn't bring ya'll. She'd take us. She really enjoyed that. She still talks about it.

This picture she has on the Millennium Family Reunion thing. "You know," she says, "I even think I have a gun hanging from my hip! Look good, you don't think that's a gun?" I said, "It could be, Carolyn." [laughing] It was taken from - she took those two pictures out of a picture - she's gonna have to show it to you.

"I can't see it." [looking at picture]

No, she's not in there. You can just barely see one of the heads in front of Momma.

"Oh, that's right! There's a couple of heads."

Well, they were in there. Guess where I got those. But, let me show the picture I took that from.

"That's the only picture I have of Grandma Nora. Don't we have any other pictures of her?"

I got some in my album. I have the one in the bedroom.

"I mean, snapshots, and stuff."

I must have some somewheres in my old pictures. I have to look through them. Got quite a few old pictures.

"I remember her cooking spaghetti, that's about the only memory I have of her. Did she cook spaghetti a lot?"

Oh, yeah, she used to cook. Oh yes! And talking about cooking spaghetti, I'll never forget, after your Aunt Nan came in from England, after she married Ray, Mom had to go into Houma, either her glasses or a doctor's visit, and she asked Nancy, "Do you think you can make the spaghetti today?" "Don't worry," Nan said, "I'll make it - I watched you." So she got the spaghetti goin', she did it good, but she grabbed the filé instead of the pepper, [Note: filé, also known as gumbo filé is ground up sassafras leaves and is used to thicken gumbo by adding right before eating - if you add it while the gumbo's still cooking, it becomes very slimy and inedible. Laughter.] the black pepper, and she put filé in there, and when they got ready to eat, everybody said, "Ugh, it's slimey!" [laughter] Nancy said, "I'll never outlive that one! " (sic) [laughter] She said, "They told me that all the time!" She said, "They kidded me more about that spaghetti I made!"

That was like when she was married to Ray and living in England still, and she'd write to me. That was during World War II. She said, " 'Nett, tell me how you make your gumbo." So when I wrote back, you know, she, her mother read the letter that I wrote back to her, 'you put this and that in your gumbo' - her momma says, "Those poor people! They're eating elephant over there?" [laughter] She thought it was 'Jumbo' instead of 'gumbo', you know! [laughing]

<pause>

Well, I guess that's about it, Bob.

"I remember having a wooden bomber. It must have been during the Second World War, as a toy. I was a kid, but it seems that for a kid it was about this big. Remember that, by any chance? It was gray, big wooden airplane, and had bombs that fell out of it."

I remember that and I remember Dad making wooden airplanes for the kids, too. You remember those? Made two of 'em.

"He made one for David; that's the only one I remember."

I thought he had made two of them.

"Do you remember how big I was when I had the bomber?"

No, but when you said that, I remembered it.

"I must have been at least three because I was walking good."

[END of FIRST INTERVIEW]

[START of SECOND INTERVIEW]

"Alright, we're ready to start. Let's see what the date is. November the tenth, 1999. Okay, anytime."

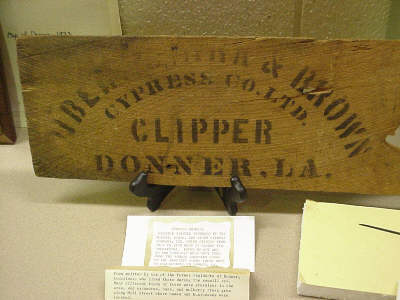

The sawmill in Donner was owned by Dibert, Stark, and Brown. And every year for Christmas since I was a little-bitty baby, a little-bitty child, I could remember we had a large Christmas tree put up in the old theater, and they'd give a gift to every kid that went to school in Donner whether their parents worked for the mill or not. But, if your daddy worked for the mill, they'd give gifts for the kids at home from a baby on up. And they gave the best gifts for Christmas! They also gave us each a pound of Elmer's chocolate candy. They had pound boxes of candy and a gift to the child as you'd go on the stage. And, uh, as a childhood friend, my best friend in Donner was Olga Boudreaux. Her and I used to go to churches together. If we had a summer bible school at her church, I'd go to it with her. Then, during Lent, she'd come and attend the Lenten service with us at our little chapel, St. Agnes.

And often we'd go, we had a beach built in Morgan City, about ten or twelve miles from Donner, and Dad would take us to the beach, two and three times during the summer months. And we'd go on, we'd have picnics on the beach, and we'd swim. The water was beautiful. It was a sandy beach.

"Was that on the Atchafalaya River?"

I don't remember what river it was. What was the name of that place? I don't remember right now.

"It wasn't in the Gulf?"

No, uh-uh. We used to go crabbing, too, there in the mornings along that lake. It was a lake. And we had wonderful teachers in Donner. And our principal was Mrs. Ingrid Peterson. And she used to tell the boys - this was right before World War II cause, uh, let's see, this was, uh, World War II was in Forty - what year did World War II start in? "1941" and this was 193. . . the early Thirties - and she knew that there was trouble brewing, and she kept telling the boys, "Look! Ya'll don't have to go to war, if ya'll don't want to. Ya'll go out in the woods, and let me know where ya'll at, and we'll bring you food, and build you a camp out there." [laughter] She was against war! She said that it was useless to go out there and get murdered and butchered!

And my grandparents lived just two doors down from us. We'd, uh, on our way to school and on our way back from school, he'd sit on that porch swing on the front of the house and he'd wait. We'd stop and give him a hug and a kiss on the way to school and on the way back from school. If we didn't stop, he hollered at us, "Come back here! I want my hug!" Grandpa Himel. Sylvania Himel.

"What did he do? Was he retired then, not working?"

Oh, he had to stop working. There was no such thing as retirement in those days. When you got too bad off to work, you just had to quit working. You didn't get no kind of pension or anything. My grandmother sewed for out to get money to keep them up. She used to sew for the Kellers [Note: name sounds like "Kellesiz"], and I think she sewed for the Gilberts and I think she did some sewing for the Paynes. She did a lot of sewing for out.

"What kind of work was he in when he was working?"

I don't know what part of the mill he worked in. But I had an uncle that worked in the mill. He worked with my brother in the Planing Mill, on the boards in the mill. Uncle Louis Himel. Then we had . . . I already told you that about . . .

"Just go down the list."

I remember when we all had the measles. They had an outbreak of smallpox in Donner at one time. So Momma put us all in one room, and she'd watch us close in case we'd break out in any kind of sores that looked like chickenpox. But then they came around and gave us shots, no, not chicken pox, smallpox. They gave us each a vaccine. Well, we were sick with that! We ran fever and everything, but we never caught it. But everybody had to get a vaccine because we had two cases of smallpox in Donner at the time.

And we had movies in this theater, but they weren't talking movies, and you could eat, eat popcorn, and make all the noise you want, because it was a silent movie. It was so funny when I went to the first movie that had talking, I really, you couldn't laugh too much or talk too loud because they'd tell you, "Shhhh!" And we found that so funny because we used to make all the noise we wanted to at the movie theater! We used to watch Charlie Chaplin and I forget . . .

"Did they have a piano player or organ to go with it?"

No! uh-un, No, no! This was silent! Nothing! Just the movie, and they'd have the words written after each scene, you know, to tell you what they were saying. They'd sell popcorn and candy and stuff, you could buy that at the door.

And we used to love to go to the drugstore. Mr. Stephans used to own the drugstore. And they had a soda bar. We could sit at the bar and buy ice cream sodas, whatever you wanted, and that was fun, you know, when we'd earn a few extra nickels, we'd go to the soda bar and get us a soda.

[Thanks to note from Frances White, March 29, 2015, I can now identify the man Annette called "Stephans" as Mr. Anatole J. Stevens who later owned a drugstore in Thibodaux on Jackson Street. He was Frances's grandfather.]"Was he the same one that played the violin at night?"

He's the same man that played the violin at night - we used to listen to him, and, uh, he was good, very good, he'd play the violin. We could sit on our front porch and listen to him.

And my longest friendship is with my friend Olga, we're still good friends, we go to Donner reunions together. I love her dearly. She's, she's one of a kind.

And sometimes during the summer months, they needed . . . a couple of teachers had asked me if I'd tutor math for some third graders. So, during the summer months sometimes, I'd some tutoring, math tutoring.

I had always wanted to be, I wanted to be a nurse when I graduated, but Mom and Daddy didn't have the money, and the Mill was getting ready to close, so I didn't have the money to go, to go to college, so I went to New Orleans and walked the streets of New Orleans looking for some kind of job. Couldn't find none. So one day a friend of my sister's asked me if I'd go with her to Lane Cotton Mill. And, I got on there as a selvedge hand. Getting paid so much an hour. And, uh, I was making more than my dad was making at the Mill. I think that's about all I can think of there.

Yes, and also, we did have a 50th class reunion, let's see we graduated in 1935, so in 1985 we had our 50th reunion, and we had a pretty good turn-out considering how many had passed away. We were lucky, because a couple of years after, the one that started the class reunion, Dr. Philip Cenac, died. And he was my mother's doctor also.

And we started, also started a fund-raising for students, to give students money in scholarship funds. And we'd put that in a fund, everybody would donate so much, and every year they'd give that to a student from Hahnville, uh, from Terrebonne High. And at this class reunion we had a character that was there. He'd had a few drinks at the bar before he came up. His name was George Himel. And he, uh, someone asked to say the prayers before the meals. And he stood up and pointed over to Buster and said, "Leave him, he's the bishop! He can do it - he's the bishop!" Cause my husband had gone to the seminaries before he graduated, so he used to always kid him about that issue. But his wife was totally embarrassed!

And, uh, also, I can remember that I was named after one of my aunts, my mother's sister. She died -- she was only three months old, her name was Annette, so my mother called me after her. Her name was Annette Himel.

"How many siblings did your mother have?"

My mother had twelve, she lost two, raised ten. [Note: she's talking about her own siblings, not her mother's.]

"No. How many siblings, sisters and brothers?"

Oh, she had, there was just three. Uncle Willie [Note: en Cajun, Nonc Willie], my mother Daisy Himel, and Louis Himel. There were just three children, and the fourth one was Annette and she died. That's about it, Bob.

Oh, yes, I was in an accident! My Dad . . . when the Mill closed in Donner, he started looking around for something to buy. So he heard that this farm in Bourg was for sale. So, he had gone over there, and we wanted to go ride and see where it was. So we took off with our cousin in a Model A car. And they were building a new road between. . . between Chacahoula and Shriever. And when we got on that road, it had been raining, and my cousin that was driving, tried to swerve, and they had a little turtle on the road, and he hit the side . . . the sides of the roads weren't quite finished . . . and it started sliding and we zig-zagged across the road twice. One side, on the right side was a big canal and on the left side a small one and a railroad track. Well, thank goodness, we turned over on the left side. I never got hurt, I just had a swollen lip, but my cousin had a broken collarbone, and the one driving had a gash in his arm, so we ended up going back to Donner. Pushed the Model A Ford back up on the road on four wheels, and headed back to Donner, only the windows were broken on it. They made them sturdy in those days! The frames didn't bend.[laughing]

"You went off the side of the road where the railroad track was, not the canal?"

Yes, but if we'd have went on the right side, we'd went into a deep canal. They had dug that canal to build the road.

[END OF SECOND INTERVIEW]

Buster Remembers

Handwritten by Hilman Joseph "Buster" Matherne on October 14, 1999 (word processed and formatted by Bobby Matherne):

I was born in Westwego on September 29, 1917. I think Dad lived a while in Montegut where Hilda was born on July 29, 1915. Dad used to cut hair in New Orleans where Uncle Percy had a barber shop on Oak Street. Dad then moved to Bourg where he had a house and a barber shop built in the early twenties. I will always remember his dog, Pete, a pointer that he had well trained. I really believed that dog could understand English. He would tell Pete he had left his matches in the shop and send him to get them. And sure enough, he would! Dad used to make a garden next to the house. When I was old enough, I would help him. We picked a lot of good vegetables in that garden, lots of butter beans, mustard and tomatoes.

Dad would earn about $I5 a week and as the family grew, heand Mom decided they had to do something to make more money. Mr. Harvey had his grocery store and house for sale. So they decided to buy it. They figured at least they could get groceries at wholesale. The first wholesale bill was for $89 and that was about all they could afford. He kept his barber shop in the back of the store and Mom would take care of the store.

I remember Dad telling us about the 1915 storm, where 500 people drowned on Last Island and about the tornado that picked up their house in Bayou Blue. He was 11 at the time and that's when his mother died.[January 9, 2019, compiled by Bobby from newspaper and oral reports] Clairville was called into the house by his mom who was at the back door of their Bayou Blue home. He recalled seeing the sky a weird orange color and his mother calling him to come indoors before the tornado picked him up and tossed him down a 100 yards away in a field. Likely the low pressure of the tornado and his fall to the ground damaged young Clairville's eardrums and caused him to wear hearing aids the rest of his life. He was in the hospital in a coma for about two weeks and awoke to find his mother and sister had been killed. His mother died when the house collapsed on her as she was calling Clairville. His sister dropped on top of her younger sister to save her and died, but saved her sister's life.Grandpa Leopold never remarried. I also remember the 1926 storm that

hit Bourg. I was at my friend's house when it started to rain and the wind kept getting stronger so we sent word to Mom that I would spend the night there, Dad moved his family across the street to a much bigger house. But the wind blew part of the house apart so Dad had to move back to their house during the storm. There is a whole lot more I remember, but I'll close now until maybe next time when we have our next reunion.

Handwritten by Hilman Joseph "Buster" Matherne on October 21, 1999 (word processed and formatted by Bobby Matherne):

I just found out that Papa did live in Montegut for while; that's where Hilda was born. After that Papa and Mom moved to Westwego. Mom, contracted smallpox and had a miscarriage at three months. After that they were poor. Aunt Lady was my Godmother. I never did know my Godfather. I was told he gave me an overcoat when I was six. I have a picture of me in the overcoat.

Papa worked in the sugar mill during the winter, and I believe he would shoot pool to make a little money. Things were real bad in the twenties.

Sometimes I would walk to the ferry and cross the river and

walk to Walnut Street where Uncle Percy lived not far from his shop. Papa would cut hair on a percentage of what he made. I remember other things about his dog Pete. Dad would give us his wallet, close Pete's eyes, and tell us to go hide it in the garden, but not too high so Pete could reach it. When we got back he would tell Pete to find his wallet, and it didn't take long to find it and bring it back. Before Pete I think Hilda had a small dog that we all loved, but somehow he died. I remember we were in the garden and buried it and made a cross and stuck it in the ground.

I remember we had a thick hedge near the Bayou and one day I was fishing and Elaine threw a piece of an old chamber pot and hit me on ahead. Did that hurt! I ran inside bleeding like a stuck hog.. We also had a hedge across front lawn. I hated to trim it, but it had to be done. Sometimes I would be chased by a swarm of bees.Before I forget, the best I remember about Papa was when at Christmas he would give all his kids and grand kids each a quarter. He would hand out a pocket of quarters every Christmas.

The thing I remember about Mom was that she baked bread. We

could hardly wait till she took it out of the oven to get a slice

of bread. She could make the best cakes. Every time they had a church fair she would bake three or four to give to the fair. I remember she tried to whip Fran but he was too smart. He would grab her by her waist so she could not get a good swing, and they would be dancing round and round.

I remember Papa was to give me a whipping. I never knew

what it was for. He told the other kids to get a branch from the hedge and if it was too small he would whip them with it. I went and hid under the bed. He said the longer I stayed the more he would whip. When I got out from under the bed, I decided I would not cry. And boy I get a whipping! I think Mom told him, "That's enough!"

Handwritten by Hilman Joseph "Buster" Matherne on November 8, 1999 (word processed and formatted by Bobby Matherne):

When I was about eight or nine years old I remember Papa sitting in the shade next to the house with his knife and hatchet carving a decoy out of cypress root which was the best root for making decoys. I used to help him make them smooth by using pieces of glass and then use sandpaper. I guess Papa made a couple of dozen. He would sell them for a dollar and a

half apiece. In the Forties I started making a few decoys to hunt over. When the plastic decoys were made we used those also. When David came out of the service he wanted to do some duck hunting and then we started making decoys. I guess in ten years we made over 1000 decoys. Later I made real fancy ones. Now David is carving since he retired. He really makes beautiful decoys.

Carolyn asked me the other day when Papa built the house that she lives in. I told her it was built in 1940 or 41 -- just a short time after I'd built my house in Westwego. I did the plumbing and Fran did the electrical work. To build the house they tore down the house near the bayou, but left the barber shop.

When Annette and I decided to get married, Papa hired a carpenter to add a kitchen to the shop so we had a place to live. Before that, Papa asked Mr. Gus, he was a salesman for Autin, if he could ask Mr. Autin to get some work for me, and he did. That was the first real job I had. I worked 12 hours a day six days a week for two dollars a day.

Papa used to like to fish a lot so we got him a rod and reel. I remember he went fishing at Point Barré, and he hooked an eight pound redfish, but didn't know how to set the drag on the reel. The more he cranked on the reel, the more the fish pulled away so he put the rod on the ground and pulled the fish to land hand over hand. We got a kick when he told us this story. Papa also was elected to serve as Justice of the Peace. I think he served a few terms then he decided not to run again.

In 1948 Mama came down with cancer. She was only 52 when she died. We all took that very hard. Papa did not know what to do so he hired Ann to do the house work and Belle to take care of the store while he kept the barber shop. It was a little over a year after Mama died when he married Belle. They loved each other very much until Papa died at the age of 81. Belle would walk to church every day and visit his grave after mass. Belle lived with Carolyn in the house that Papa built until her death at 92.

== == == == == == Compiled, Written by Bobby Matherne == == == == == == == == ==

The Michael J. Donner Story

How the Town of Donner Got Its Name

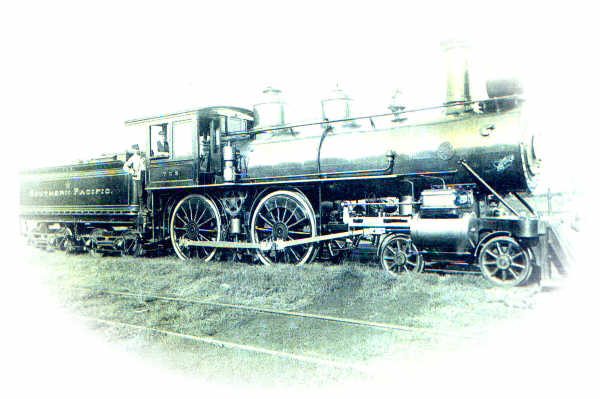

My father-in-law, Percy Francis "Dick" Richards told me this story that he had heard from a Donner descendant which I recollect here for you. It's about a train engineer who used to stop at a small sawmill town in South Louisiana. The sawmill had just been built and with a town growing up around it. It soon became his regular stop. One day he asked a workman near the stop, "What's the name of this town?" The workman shouted back, it doesn't have a name! What's your name?" "Donner!" the engineer yelled back over the sound of the engines. "Good! That's what we'll call it!" And that's how the town of Donner got its name, and that's what it's been called ever since. The following history of the town's namesake was written by Leah Durkes Esteve, Michael Donner's great-granddaughter (Reprinted here by Permission). The photo shows Michael Donner leaning out of the window of his Southern Pacific steam engine.Bobby Matherne

Bernard J. Donner and Mary Ann Shanley Donner emigrated from Longford, Ireland to the United States in the early 1800's with their two sons Michael and Patrick. In 1844 they purchased a parcel located al the comer of the present day Evelina Street and Pacific Avenue in the Algiers Section of New Orleans, Louisiana. The family resided at This location until 1995 when the property was sold. The present home was built in 1880 When Michael's family outgrew the original homestead.

Michael married Eliza Jane Daly and together they had eight children seven boys and one Girl. They were Joseph, William, Edward, Timothy, Frank, Charles, Richard, and Mary Elizabeth. Eliza Jane died in 1882 when their youngest child was only 2 years old. Mary was placed with the Ursuline nuns boarding school as it was not proper to bring up one girl with all of the boys without a mother. She was 10 when her mother died

Michael was an engineer with the Southern Pacific Railroad He had his own engine And would pick up the train from a barge that crossed the Mississippi River between Elysian Fields Avenue and the Southern Pacific Railroad yard. From this point he would Travel to the west probably as far as Lafayette. One of his regular stops was a sawmill West of Shriever, Louisiana. A small town grew up and they named it Donner, Louisiana After him. This was quite an honor. He about 30 years after his wife died and never Remarried.

His son William followed in his father's footsteps and was an engineer with the Southern Pacific Railroad. He had the honor of taking the first train over the Huey P. Long Bridge When it was completed in I think 1935. His sister, Mary, was right there along for the ride.

Mary became the matriarch of the family. She and her husband Will Schroder moved back Into the old homestead after their marriage to take care of her father in his older years. She Remained in this house until her death in 1965.

Charles Donner became Secretary of the Levee Board for the state of Louisiana. He was a Big Huey P. Long supporter.

In 1927 Mary's daughter and son-in-law Leah and David Durkes moved into The old homestead as her husband lost his job and she was pregnant. Then in 1932 Will Died and Leah and family stayed to take care of her mother. They resided here until their Deaths in 1975 and 1976. Their son, David William, remained in the house until his death In 1987. Leah's grandson lived in the house until it was put up for sale in 1995. The Neighborhood was going down at the time. It was costly to keep up this big old house and Jay was single. It was impossible to find decent renters who would care for the property and Upkeep and taxes were quite high.

I do not know more about the other children of Mike as most of them were deceased before I was born. I know that Tim was left behind lost in the swamps on an outing and it took him Three days to find his way out. He was eaten by mosquitoes and crabs and died shortly After this incident.

Do memories make you sad? Unhappy? Angry? Anxious? Feel down or upset by the world situation? Plagued by chronic discomforts like migraines or tension-type headaches? At Last! An Alternative Approach to Removing Unwanted Physical Body States without Drugs or Psychotherapy, e-mediatelytm!

>

>