As John Frederick Nau observed, the Germans' part in building an important

presence in the lower Mississippi valley has been overshadowed to a great extent by

the word of the French and the Spanish. Indeed, in the 1950s, Nau observed that

considerable surprise is often registered "when one ventures to suggest that other

Europeans besides the French and Spanish have had a part in the forging of new

Orleans life, among these, the immigrants from Germany."

— Don Heinrich Tolzmann in the Foreword

This book came to me as a Christmas present in 2004 from my daughter, Maureen Bayhi, and

a couple of months later I attended a lecture by Ellen Merrill at the German Cultural Center in

Gretna. I learned so much from her lecture and a subsequent lecture at an another venue that I

postponed reading the book for about a year. During that time, I began to ponder all the things I

learned from her talks.

Card-playing on Sundays was something I knew as a small boy. My great-uncle everyone

called Parran (Cajun for Godfather) was always playing Pedro, a Cajun form of bridge, played only

in South Louisiana, Michigan, and Finland so far as I've been able to discover. I remember those

long afternoons as I stood next to Parran and Grandpa Babin as they puzzled over their cards and

kept the scores in a cryptic fashion with circles around some of the numbers. Even today, my elderly

Matherne aunts are still playing cards together. Since all my relatives seemed to me to be Cajun

French, I had assumed that the practice of playing cards on a Sunday afternoon was a French custom.

Imagine my surprise when Dr. Merrill explained that this was a German custom! I went back

and began checking off all the German names of my ancestors:

Grandpa Babin was married to an Himel (pronounced EE-MEL) but originally it was Himmel, a

German name. Her brother, Louis Himel, was known as Parran and was definitely German

descendant. Since my Matherne line is all German descent as well, I came to see how card playing

was actually a result of our German ancestors and not of my Acadian-French ancestors. Until Dr.

Merrill pointed it out, I had never reflected on how different an afternoon of family togetherness and

card-playing fun differed from the typical Anglo-Saxon Protestant's keeping of Sunday as a day of

prayer and somber reflection. Paradoxically, much of the causal laissez bon temps roulez attitude of

South Louisiana can be laid at the feet of the German immigrants who merged into the French

culture they found.

My own name bears a little explication. My daughters went to France and tracked down our first Matherne ancestor: Johann Adam Matern in Rosenheim, Germany, a town now situated an area of France that is still German-speaking. When Johann Matern arrived in Louisiana about 1722 he registered his

family at the Hahnville Courthouseand settled in what is known as the German Coast.

His two sons are recorded as Nicholas Matherne and Jean Materne. One can only surmise that the

addition of the extra "e" and the "h", both of which are silent in the french-pronunciation of the

name, were added by some french-speaking Cajun who registered the births of the two sons. One can

imagine one clerk adding the "e" when told that Jean Matern was born and another adding the "h"

and the "e" when Nicholas was born. These recording errors make it very likely to my mind that all

extant Matherne's and Materne's are related to each other.

In his Foreword, Tolzmann writes about John Nau who wrote the other book about the

German roots of Louisiana.

[page 13] When John Fredrick Nau wrote in the 1950s his German People of

New Orleans, 1850-1900, he observed that the Germans of the city were still

inspired by the same determination and loyalty that had motivated them to build

their communities in the former century. He found this to be apparent in the

continuation of their churches, schools, and singing and benevolent societies as

well as in their businesses and industries, many of which are still in operation.

He noted that "the influence of the Germans upon the city of New Orleans still

lives, while German-American contributions to the building of New Orleans are

visible on every hand." Nau commented that, in the research for his history of

the New Orleans Germans, he repeatedly found that German-Americans

"helped to make New Orleans a city of commerce, industry and business. They

built New Orleans." He concluded, "To read the history of New Orleans and

Louisiana aright, it is important to consider carefully the part played by the

German element of the city in molding the culture and life of this city."

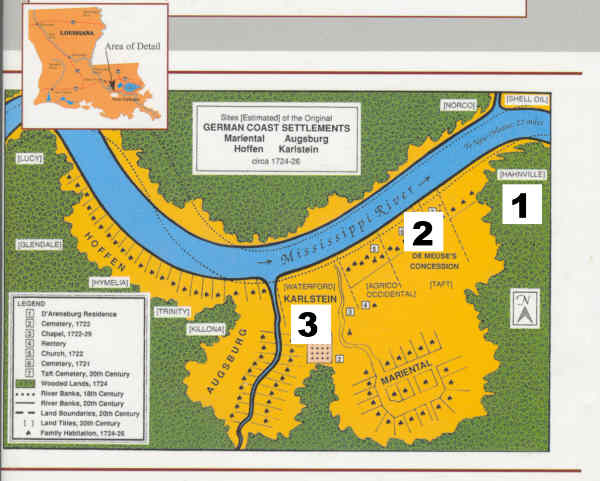

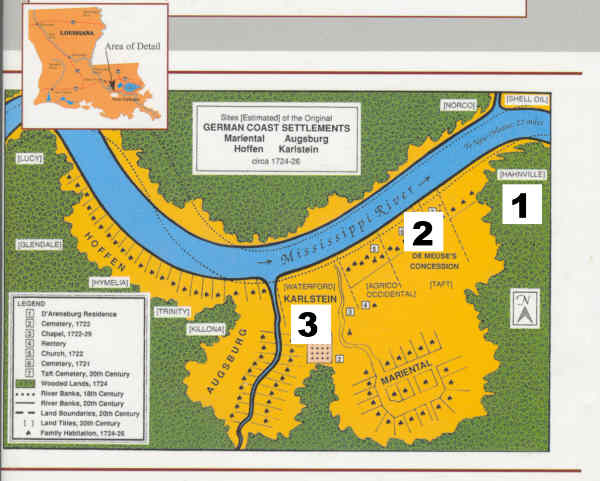

On the map on the back of the book jacket, shown above, I have added three markers to

significant places where I spent a lot of time during my life. At the time I was there, I had no idea

that these were settlements of the German Coast dating back to 1724. From 1955 through 1958 I

attended Hahnville High School (1). I returned from my first job after LSU to take a job from 1966

through 1969 years at the Union Carbide Chemical Complex (2) in Taft, which was originally called

"De Meuse's Concession." Once more I returned to Louisiana in 1976 and in 1981, I took a job at

the Waterford 3 Nuclear Power Station (3) in what was originally called Karlstein in the early

eighteenth century. Fourteen years later I took early retirement from there to become a writer full-time. Twenty years of my daily life were spend on the grounds of these centuries old German

settlements and only upon receiving this book and reading it did I fully become aware of the nature of the

places I had been going to school and working. I lived elsewhere during these twenty years, but, true to

the industrious nature of the original settlers, my ancestors, I worked long, hard hours upon these three plots of

ground.

On the map on the back of the book jacket, shown above, I have added three markers to

significant places where I spent a lot of time during my life. At the time I was there, I had no idea

that these were settlements of the German Coast dating back to 1724. From 1955 through 1958 I

attended Hahnville High School (1). I returned from my first job after LSU to take a job from 1966

through 1969 years at the Union Carbide Chemical Complex (2) in Taft, which was originally called

"De Meuse's Concession." Once more I returned to Louisiana in 1976 and in 1981, I took a job at

the Waterford 3 Nuclear Power Station (3) in what was originally called Karlstein in the early

eighteenth century. Fourteen years later I took early retirement from there to become a writer full-time. Twenty years of my daily life were spend on the grounds of these centuries old German

settlements and only upon receiving this book and reading it did I fully become aware of the nature of the

places I had been going to school and working. I lived elsewhere during these twenty years, but, true to

the industrious nature of the original settlers, my ancestors, I worked long, hard hours upon these three plots of

ground.

The bank on the inside of a bend in the river is called a "pointe" and the river tends to scour

away the land. On the outside of a bend in the river, the land is called a "côte" or "coast" and the

river tends to add land to that side. Thus, the inside bank of the river was called the Côte des

Allemands by the French, while the lake was called Lac des Allemands, and the town, Village des

Allemands. The town name in St. Charles Parish is known simply as Des Allemands, while Lake Des

Allemands and the German Coast are the other names used today. "This settlement, the fourth oldest

in the United States, was largely unknown to the historians of German immigration until recent

years." (Page 81)

From the beginning the Germans were assimilated into the French culture of the region.

[page 42] Since the German pioneers were brought into a totally French milieu,

their language and culture in time were lost. No German schools or Protestant

congregations were established in the colony, leaving the settlers on the Côte des

Allemands unable to record their traditions for succeeding generations. The lack

of language and religious instruction in German accelerated their assimilation,

as did intermarriage with their French fellow citizens. Both men and women of

German background were considered very desirable marriage partners. The

males were known for their dedication to hard work and devotion to duty, while

the women were considered diligent housewives and healthy, prolific mothers.

Church registers showed that these intermarriages produced as many as twenty

or more children.

The German Coast survived the hurricane of 1722 and the various Indian attacks and went on

to prosper by becoming the greengrocer for the city of New Orleans. Indigo was a cash crop for a

time until some bug wiped it out and it was replaced by sugar cane. The esteem with which German

settlers were held is apparent in this note to the French government to increase the settlement by

German-speaking nationalities.

[page 46] The French colonial prefect, Pierre Clement Laussat, made the

suggestion to increase the population of Louisiana primarily by bringing in

Germans. In 1803 he supported this recommendation with the following words

(Archives Nationales, Ministere des Colonies, Messidor [June 19-July 18] 6, Col.,

C 13 A, vol. 52, fol. 199):

This class of peasants, especially of this nationality, is just the kind

we need and the only one that has always done well in this area,

which is called the German Coast. It is the most industrious, the

most populous, the most prosperous, the most upright, the most

valuable population segment of this colony. I deem it essential that

the French government adopt the policy of bringing to this area

every year 1,000 to 1,200 families from the border states of

Switzerland, the Rhine and Bavaria.

In 1847, the immigration of Germans was aided by the German

Society of New Orleans who boarded all vessels carrying immigrants

to gather the Germans into a group.

[page 58] Because most of these new arrivals spoke no English, the agent's first

duty was to shepherd them through customs. For those traveling inland,

transportation via the Mississippi River was arranged. The German Society also

assisted all German immigrants choosing to remain in New Orleans. These new

members of the community were provided with work, shelter, childcare, medical

assistance, and funds, if necessary.

When yellow fever disappeared for a few years, the improved conditions were attributed to better drainage and the city was declared plague free, which re-opened immigration to Germans again. This proved to disastrous to the German immigrants. They arrived at ages older than five years old, the age at which yellow fever immunity is no longer available. Children below that age who are infected will sustain a lifelong immunity(1).

[page 64] However, during the summer of 1853, yellow fever broke out as never

before. Eight thousand residents fell victim to this plague, almost two-thirds of

whom were German. The fever raged mainly among the foreign born, who had

no natural immunity. The many who found work digging the canals of the city

were particularly vulnerable. During the height of this epidemic the society

forwarded new arrivals up the river free of charge to avoid a stopover in New

Orleans.

To combat the plague the Howard Association was organized to help take

care of the victims in the city. Temporary clinics and refuges for orphans were

set up, and every known means was used to limit the spread of the yellow plague.

But the epidemic defied all attempts to contain it. Whole families were wiped out

or separated forever. Many orphans were too young to know their last names.

New Orleans was known as the only free port to the poor of the world and the German

Society fought against the prejudices against the Germans, pointing out that the "states associated

with the German Society received valuable immigrants, chiefly farmers of excellent character,

industrious habits, and sufficient resources." (Page 66)

In the middle of the nineteenth century, Michael Hahn became the governor of Louisiana and

the "first German-born citizen to become a governor of an American state". (Page 71) He laid out a

town in St. Charles Parish which bears his name today. Hahnville is the parish seat and the

courthouse originally had the Hahnville High School, where I graduated, next door. Today HHS is

located on Hwy 90 west of Boutte but retains its original name.

In the chapter "Settlement Patterns" I learned that Gretna, the town in which I live, had a no-slaughter house rule, whereas its abutting down river neighboring town, Algiers welcomed the

slaughterhouse business. Remember that the Mississippi River was a fast-flowing river almost a

mile-wide and hundreds of feet deep at New Orleans. Bridges were yet a century away in the early

nineteenth century, so all the cattle from the river westward came to a crashing halt at the river's

edge. Either you slaughtered them, as Algiers did, or you shipped them on hoof across the river by

ferry, as Gretna did. Directly across the river from Gretna was the City of Lafayette which was the

slaughterhouse district of New Orleans. Algiers became an industrial area and Gretna maintained a

rural aspect.

Another surprise for me was to discover that it was my German ancestors who were

responsible for the rice farming that is a mainstay of many Louisiana farms today. Before the

Germans figured out how to farm rice dependably, people grew only “providence rice” as explained below.

[page 93] These hardy, industrious Germans settled down to rice farming. Up to this

point only "providence rice" had been produced, so named because sufficient rain to

produce a crop was left to providence. The scientific bent of the German mind soon

enabled them to develop a new irrigation system of dams, levees, and pumps based on

the technology of their former Dutch neighbors. In the hands of the Germans, the

cultivation of rice, which their Acadian neighbors had grown only in small plots,

became a stable and profitable Louisiana industry. The German rice farmers

prospered, bought more land, and spread throughout the surrounding area.

The author gives us lists of German related place names such as cities, towns, and streets,

German-designed buildings, German-run Bakeries, Drugstores, and Banks. Also grocery stores,

jewelers, watchmakers, cabinet makers, foundries, blacksmiths, mortuaries, Florists, Publishers,

breweries, and beer gardens. The list of German language newspapers and the dates of their

publication shows that New Orleans had a large German-speaking population into the first quarter of

the twentieth century, when two World Wars against Germany led to restrictions on German

speaking, with prison sentences of up to 60 years merely for speaking German aloud in public.

Chapter Six is devoted to Religion and Education and describes the many churches, synagogues, and

schools begun by the German residents. Also a comprehensive list of cemeteries around the city and

neighboring communities. This is followed by Chapter Seven on Social Concerns where one can find

details of orphanages, homes for the aged, societies and organizations such as benevolent societies,

cultural societies, drama societies, fraternal societies, masonic societies, secret societies, heritage

societies, military societies, political societies and music/singing societies. And no list of lists would

be complete without a list of the bars, saloons, taverns, theaters, and movie houses.

Some preeminent events were held in New Orleans. The first German-language performance

in America of Faust took place in the city in 1845. The first publication of the popular Southern

anthem, "Dixie", was published in the city in by the Werlein's Music Company. The Sängerbund of

North America held it 1890 convention here and a huge hall was built at Lee Circle to house 1,700

singers, a 100-piece orchestra, and 6,000 spectators. The first night club in the country was thought

to be the Cave in the basement of the Grunewald Hotel, which was later to become the Roosevelt, later the Fairmont, and after Katrina, was resurrected as the Roosevelt Hotel again.

To close out the book, Chapter Nine gives us synopses of the lives of Prominent Germans

and German-Americans. There are several persons on the list I recall. One is Hermann Bacher

Deutsch who wrote for the Times-Picayune. I read his column up until the mid-1960s. The other

names I recall from their products and businesses, such as Alexander Julius Heinemann's Pelican

Stadium on Tulane and Carrollton, Fritz Jahncke's ubiquitous cement trucks, Peter Jung's Hotel on

LaSalle and Canal Streets, and Georg Kleinpeter's milk which I drank while at LSU. My grocery

store during early married life was due to Garrett Schwegmann, Sr. and the music store where I

bought my trumpet music was founded by Philip Peter Werlein. The one person on the list I knew

personally was Stanley Ott. He was head of the Newman Club at LSU and assistant pastor of Christ

the King church on campus. When I presented my first-born, my daughter Maureen, for baptism, it

was Reverend Ott who performed the baptism together with the Monsignor Robert Tracy.

If there's anything you wish to know about the German influence in Louisiana and especially

in New Orleans where the immigrants were concentrated, this book will reveal it to your study. A

must book for your reference shelf for things germane to Germans in the region.

---------------------------- Footnotes -----------------------------------------

Footnote 1.

This is an hypothesis on my part, but it is based on evidence that settlers born in the area were thought to be

immune from Yellow Fever — probably because each had a slight case of it while a child and recovered, acquiring thereby

a lifelong immunity to the disease. One famous person who recovered about age five was Rudolf Matas, a doctor who

specialized in Yellow Fever, and who lived to be 97 and maintained a lifelong immunity to the disease after that one bout

with the disease about five. He claims to have checked and found antibodies to the disease in his own bloodstream at age

96. The age of five is known as the memory transition age in the science of doyletics and any doylic memories of a bout

with Yellow Fever before that time would be stored and contain the ability to create antibodies for the rest of a person's life.

Return to text directly before Footnote 1.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~^~

Any questions about this review, Contact: Bobby Matherne

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

22+ Million Good Readers have Liked Us

22,454,155

as of November 7, 2019

Mo-to-Date Daily Ave 5,528

Readers

For Monthly DIGESTWORLD Email Reminder:

Subscribe! You'll Like Us, Too!

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

Click Left Photo for List of All ARJ2 Reviews Click Right Bookcover for Next Review in List

Did you Enjoy this Webpage?

Subscribe to the Good Mountain Press Digest: Click Here!

CLICK ON FLAGS TO OPEN OUR FIRST-AID KIT.

All the tools you need for a simple Speed Trace IN ONE PLACE. Do you feel like you're swimming against a strong current in your life? Are you fearful? Are you seeing red? Very angry? Anxious? Feel down or upset by everyday occurrences? Plagued by chronic discomforts like migraine headaches? Have seasickness on cruises? Have butterflies when you get up to speak? Learn to use this simple 21st Century memory technique. Remove these unwanted physical body states, and even more, without surgery, drugs, or psychotherapy, and best of all: without charge to you.

Simply CLICK AND OPEN the

FIRST-AID KIT.

Counselor? Visit the Counselor's Corner for Suggestions on Incorporating Doyletics in Your Work.

All material on this webpage Copyright 2019 by Bobby Matherne