In Oliver Sacks's book, A Leg to Stand On, he mentions on page 89 that his favorite

relative, a maiden aunt of 82 years old, visited him in the hospital when he was recovering

from a serious accident in which he lost complete control over his legs. It was her birthday

and Sacks gave her a book, The Maiden Aunt in Fact and Fiction. She loved it and said she

loved being a maiden aunt with 230 grand nieces and nephews. Then she reached in her bag

and pulled out a book for her favorite nephew Oliver saying, "And I've got a birthday-book

for you. You were away on your birthday, up in the Arctic. I know you love Conrad. Have

you read this?" Sacks said, "No, but I like the title."

[page 89, A Leg to Stand On ] "Yes," she said, "It suits you. You've

always been a rover. There are rovers, and there are settlers, but

you're definitely a rover. You seem to have one strange adventure after

another. I wonder if you will ever find your destination."

After reading that page I ordered a copy of The Rover, and to complete the symmetry, I read it while on an adventure down to Antarctica. We roved from Rio de Janeiro down through Uruguay, Buenos Aires, down to Ushuaia which is the end of world, the southmost point of any landmass on the Earth. Then we cruised into Palmer Station, a USA Experimental Station on the Antarctic Peninsula and returned to Buenos

Aires. It's the kind of long sea journey that marks so many of Joseph Conrad's stories.

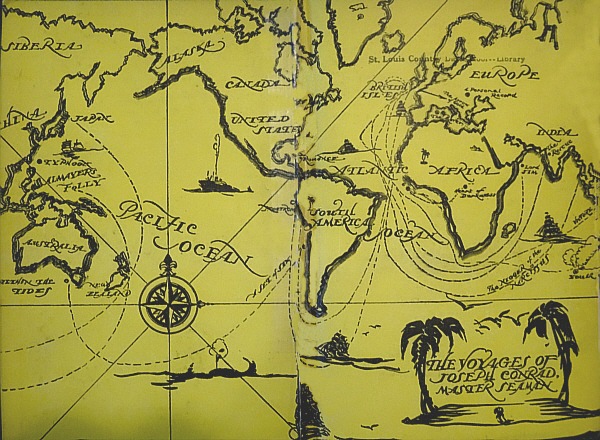

Inside the front cover of this hardback book is a wonderful diagram which illustrates

where Conrad's various novels are set in the world. It is a rough world map covering the

book's paste down and free endpapers. A dotted line draws the long voyages between India

and England for Lord Jim, between South America and Australia in A Set of Six, along the

Congo River in The Heart of Darkness, e.g., and for The Rover, the title simply fills the

Mediterranean Sea. Even though he was mostly ashore during this novel, he spent a lot of

time looking out on the sea from the hills near his residence outside of Toulon, France.

Conrad gives away the ending of the novel on the dedication page:

To

G. Jean Aubry

In Friendship

This Tale of the Last Days of a

French Brother of the Coast

Now that we know all about it, we can proceed to read it with interest. Our hero is

Master-Gunner Peyrol who lets down his anchor for the final time near the Toulon

harbor on the coast of France. Peyrol gives us a description of the dock area, and,

already on page 2, Conrad bombards us with recondite words of Peyrol's time which

was during the aftermath of the French Revolution. Although the revolution happened

while he was at sea, he had to justify his dislike for the over turned royalty.

[page 2] Peyrol took a survey of the quay. Groups were forming

along its whole stretch to gaze at the new arrival. Peyrol noted

particularly a good many men in red caps and said to himself: "Here

they are." Amongst the crews of ships that had brought the tricolour

into the seas of the East, there were hundreds professing sans-culotte

principles; boastful and declamatory beggars he had thought them.

But now he was beholding the shore breed. Those who made the

Revolution safe. The real thing.

Not familiar with the term sans-culottes, which seems to indicate people not

wearing pants, I looked it up, and what I found wasn't very helpful. Typically that's the

case with an idiomatic expression in a foreign language. Then it hit me that culottes

must mean "fancy pants" and that would make sans-culottes a perfect term for the

common people who could not afford bread, much less fancy pants. The revolutionaries

apparently adopted the term sans-culottes for themselves to indicate their disdain for

those who did wear fancy pants — the loyal royals who deserved their turn under the

guillotine.

The post-captain in charge of admitting arrivals to France in the harbor attacks

Peyrol, apparently as a way of acquiring his credentials.

[page 4] "You must have been a deserter from the Navy at one time,

whatever you may call yourself now."

Peyrol is nonplussed and turns the tables on the shabbily dressed post-captain.

[page 4] "If there was anything of the sort it was in the time of kings

and aristocrats," he said steadily. . . . I knocked about the Eastern

Seas for forty-five years — that's true. But let me observe that it was

seamen who stayed at home that let the English into the Port of

Toulon." He paused a moment and then added: "When one thinks of

that, citoyen Commandant, any little slips I and fellows of my kind

may have made five thousand leagues from here and twenty years

ago cannot have much importance in these times of equality and

fraternity."

The post-captain resumes his vague attack on the Gunner Peyrol, knowing that he is

a custom official with the ability to chop the head off anyone he doesn't like or anyone

he believes is lying to him. It is the landlubbers versus the brothers of the coast and the

post-captain controls the domain of the land, and he wants Peyrol to know it. What

ensues is a volley of wits and Peyrol refuses to take a defensive posture — he merely

states the facts.

[page 4] "As to fraternity," remarked the post-captain in the shabby

coat, "the only one you are familiar with is the Brotherhood of the

Coast, I should say."

"Everybody in the Indian Ocean except milksops and

youngsters had to be," said the untroubled Citizen Peyrol. "And we

practised republican principles long before a republic was thought

of; for the Brothers of the Coast were all equal and elected their own

chiefs."

"There were an abominable lot of lawless ruffians,"

remarked the officer venomously, leaning back in his chair. "You

will not dare to deny that."

Citizen Peyrol refused to take up a defensive attitude. He

merely mentioned in a neutral tone that he had delivered this trust to

the Port Office all right, and as to his character he had a certificate

of civism from his section.

Peyrol was a patriot and entitled to his discharge, which he duly received, and he

ignored the whispers of the pencil-pushers (quill-drivers) as he walked to the door. He

hires a farmer to haul him to the coast, giving the excuse of a grievous wound for his

awkward entry into the cart. When he recognizes an area where he lived as a youth some

fifty years earlier, he gets out the cart near an inn and asks a woman who resembled his

mother for a man to help him move his luggage into the inn. She provides him a laborer

to move his baggage. But Peyrol stands at the gate until the carters left with their cart

filled with empty wine-casks. After he had eaten his supper in silence, he obtains a

candle and walks slowly up the staircase which creaked as if he were carrying a heavy

load.

[page 11, 12] The first thing he did was to close the shutters most

carefully as though he had been afraid of a breath of night air. Next,

he bolted the door of the room. Then sitting on the floor, with the

candlestick before him between his widely straddled legs, he began

to undress, flinging off his coat and dragging his shirt over his head.

The secret of his heavy movements was disclosed then in the fact that

he had been wearing next his bare skin — like a pious penitent his

hair-shirt — a sort of waistcoat made of two thickness of sail-cloth

and stitched all over in the manner of a quilt with tarred twine.

Peyrol was carrying about 65,000 francs in coins of various foreign currencies, and

he wanted a safe place to dig a hole to bury out of sight the loot he had laboriously

carried from the locker of the ship. It consisted of gold coins, Dutch ducats, Spanish

pieces, and English guineas, and he was careful no one knew about his treasure. He

knew no customs-guard would dare to attempt to search a prize-master headed to the

port offices to make his report. It worked and now he needed a place to stay and found

one at a nearby farm. While waiting for the master of the Escampobar Farm to arrive

and give him permission to stay, Peyrol knew he was ready. He thought, "I have seen

everything", and thus was ready to face anything without showing a sign of surprise.

[page 25] By the time he had heard of a Revolution in France and of

certain Immortal Principles causing the death of many people, from

the mouths of seamen and travelers and year-old gazettes coming out

of Europe, he was ready to appreciate contemporary history in his

own particular way. Mutiny and throwing officers overboard. He

had seen that twice and he was on a different side each time. As to

this upset, he took no side. It was too far — too big — also not

distinct enough. But he acquired revolutionary jargon quickly

enough and used it on occasion, with secret contempt. What he had

gone through, from a spell of crazy love for a yellow girl to the

experience of treachery from a bosom friend and shipmate (both

those things Peyrol confessed to himself he could never hope to

understand), with all the graduations of varied experience of men an

passions between, had put a drop of universal scorn, a wonderful

sedative, into the strange mixture which might have been called the

soul of the returned Peyrol.

We have seen the secret treasure and gotten a view into the soul of Peyrol, so

different from the innocent lad of eleven who first went to sea as a stowaway on a ship.

As for the things he professed he could never hope to understand, rightly understood,

only karma can explain some things which can only be balanced by working out over

multiple lifetimes.

Joseph Conrad writes strong prose and delicate prose equally well. Take this

example; "The sky rested lightly on the distant and vaporous outline of the hills; and the

immobility of all things seemed poised in the air like a gay mirage." (Page 31) He has

shown us the rover's soul of Peyrol, and now undergoes to explain how this soul has

come to find its rest here along the remote shoreline of Toulon.

[page 31] Whatever enchantment Peyrol had known in his

wanderings it had never been so remote from all thoughts of strife

and death, so full of smiling security, making all his past appear to

him like a chain of lurid days and sultry nights. He thought he would

never want to get away from it, as though he had obscurely felt that

his old rover's soul had been always rooted there. Yes, this was the

place for him; not because expediency dictated, but simply because

his instinct of rest had found its home at last.

Even though his soul had found rest, Peyrol became concerned about the curious

movements of the English ship. A shot fired one night seemed to be a signal to someone

on shore. Peyrol began to look out of his second-floor windows at the night sky and particularly at the sea, and he began to form a plan. He had already salvaged a tartane, a

small fishing boat, which he kept ready for sea transport if he needed it, and a friend

Michel to go with him.

[page 100] Often waking up at night he would get up to look at the

starry sky out of all his three windows in succession, and think:

"Now there is nothing in the world to prevent me from getting out to

sea in less than an hour." As a matter of fact it was possible for two

men to manage the tartane. Thus Peyrol's thought was comfortingly

true in every way, for he loved to feel himself free, and Michel of the

lagoon, after the death of his depressed dog, had no tie on earth. It

was a fine thought which somehow made it quite easy for Peyrol to

go back to his four-poster bed and resume his slumbers.

A plan begins to unfold in Peyrol and the French Lieutenant Real's minds: a way to

get a dispatch into the British hands which will deceive Admiral Nelson into a false

move which would be costly to his fleet.

[page 143] This scheme of false dispatches was but a detail in a plan

for a great, a destructive victory. Just a detail, but not a trifle all the

same. Nothing connected with the deception of an admiral could be

called trifling. And such an admiral too. It was, as Peyrol felt

vaguely, a scheme that only a confounded landsman would invent. It

behooved the sailors, however, to make a workable thing of it.

The main problem was to get the false dispatch into Admiral Nelson's hands

without arousing suspicions that it was intended for him or else its effect will be nil.

Peyrol knew the deception could not be maneuvered by mere words, but rather by deeds.

[page 143] The old rover had enough genius in him to have arrived

at a general conclusion that if they were to be deceived at all it could

not be done very well by words but rather by deeds; not by mere

wriggling, but by deep craft conceal under some sort of straight-forward action.

It soon becomes clear that the rover Peyrol is headed back to sea in his little tartane

as part of that deed which will steer the Admiral into harm's way. In a beautiful

metaphor Peyrol comments on the seaworthy nature of his fishing boat.

[page 254] The tartane, obeying the helm, fell off before the wind,

with her head to the eastward.

Peyrol murmured: "She has not forgotten how to walk the

seas." His subdued heart, heavy for so many days, had a moment of

buoyance — the illusion of immense freedom.

Was Peyrol going to freedom on the seas or to freedom from the bounds of earth and

sea? Clearly, he was no longer to be a landsman, stuck on a spit of land overlooking the

sea, but on the sea, in battle again, if only through a battle of wits with a worthy

opponent, the great British Admiral Nelson. We have walked the land with Peyrol from his cottage

down to the sea and back up. We have stood beside him as he observed the surreptitious

movements of the British corvette from his upstairs windows. We have listened to his

thoughts as he planned carefully what to do, and how carrying out this plan would affect

the rest of his life. In the end it was the feeling of freedom, of walking the seas again, that shaped his actions and the rest of his life.

~^~

Any questions about this review, Contact: Bobby Matherne

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

22+ Million Good Readers have Liked Us

22,454,155

as of November 7, 2019

Mo-to-Date Daily Ave 5,528

Readers

For Monthly DIGESTWORLD Email Reminder:

Subscribe! You'll Like Us, Too!

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

Click Left Photo for List of All ARJ2 Reviews Click Right Bookcover for Next Review in List

Did you Enjoy this Webpage?

Subscribe to the Good Mountain Press Digest: Click Here!

CLICK ON FLAGS TO OPEN OUR FIRST-AID KIT.

All the tools you need for a simple Speed Trace IN ONE PLACE. Do you feel like you're swimming against a strong current in your life? Are you fearful? Are you seeing red? Very angry? Anxious? Feel down or upset by everyday occurrences? Plagued by chronic discomforts like migraine headaches? Have seasickness on cruises? Have butterflies when you get up to speak? Learn to use this simple 21st Century memory technique. Remove these unwanted physical body states, and even more, without surgery, drugs, or psychotherapy, and best of all: without charge to you.

Simply CLICK AND OPEN the

FIRST-AID KIT.

Counselor? Visit the Counselor's Corner for Suggestions on Incorporating Doyletics in Your Work.

All material on this webpage Copyright 2019 by Bobby Matherne

![Click to return to ARJ Page, File Photo of Joseph Conrad, Credit: George Charles Beresford [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.doyletics.com/arj/theroaut.jpg)